peter hanson's field guide to interesting film

“The Vanishing” aka “Sporloos” (1988). One of the creepiest thrillers ever made, this Dutch-French coproduction blends the sleek plotting of a Hitchcock romp with the unsettling gamesmanship of a Polanski mindfuck. When young traveler Saskia (Johanna ter Steege) disappears, her boyfriend Rex (Gene Bervoets) searches relentlessly for her until discovering she was abducted by a psychopath named Raymond Lemorne (Bernard-Pierre Donnadieu). Raymond, and the film itself, play on the fear of the unknown when Raymond tells Rex the only way he’ll learn what happened to Saskia is to let Raymond do the same thing to him. The ending is a genuine shocker, the kind of brutal denouement that hangs with viewers for years afterward. The 1993 American version of “The Vanishing,” with Kiefer Sutherland and a very creepy Jeff Bridges, is pedestrian compared to the original, especially since it wimps out in the finale.

"Vatel" (2000). As sumptuously produced as the grand feast at the center of its narrative, this peculiar historical drama uses an unexpected character as the eyes through which viewers discover the splendor and terror of Louis XIV's France. Gerard Depardieu winningly plays Vatel, a steward charged with an impossible task. When a destitute prince sees a last chance to restore his status by inviting the Sun King to his estate for a lavish party, the steward is charged with organizing the event. A noble soul steeped in the tradition of extraordinary service, Vatel culls every available resource, making compromises so clever they almost qualify as sleight of hand. Amid the frantic preparations, Vatel falls for a lady of the court (Uma Thurman), and struggles to avoid political crossfire. Though the love story never quite clicks, the picture benefits from its unusual combination of intimate character dynamics and resplendent visuals.

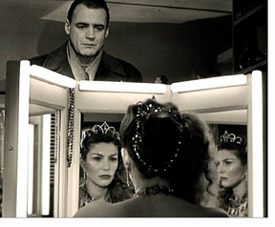

Venora, Diane. Actor, b. 1952. With her regal poise and worldly air, Venora brings grown-up sophistication to even the smallest roles, so when she's given room to plumb real depths of character, she's quite a force. A veteran of the New York stage known for her Shakespearean roles, she scored right out of the gate, elevating the underwritten leading-lady role in the horror picture "Wolfen" (1981) with her wry gravitas. Unfortunately, the movie tanked, so it wasn't until she played Charlie Parker's long-suffering wife Chan in Clint Eastwood's jazz biopic "Bird" (1988) that Venora won real attention for her movie work, including a Golden Globe nomination. A quiet stretch followed, but when she reemerged in the mid-'90s, her elegant intensity was undiluted. In 1995's "Heat," she matches screen paramour Al Pacino in conveying operatic ennui; in 1996's "Romeo + Juliet," she delivers a bold take on the Lady Capulet role; and in 1997's "The Jackal," she has a grand time playing a tough-talking, gun-toting Russian soldier. More recently, she's appeared as an NSA advisor on the scifi series “The Vikings” (2005-2006) and as a mother with a drug problem in the indie "Self Medicated" (2005).

Venora, Diane. Actor, b. 1952. With her regal poise and worldly air, Venora brings grown-up sophistication to even the smallest roles, so when she's given room to plumb real depths of character, she's quite a force. A veteran of the New York stage known for her Shakespearean roles, she scored right out of the gate, elevating the underwritten leading-lady role in the horror picture "Wolfen" (1981) with her wry gravitas. Unfortunately, the movie tanked, so it wasn't until she played Charlie Parker's long-suffering wife Chan in Clint Eastwood's jazz biopic "Bird" (1988) that Venora won real attention for her movie work, including a Golden Globe nomination. A quiet stretch followed, but when she reemerged in the mid-'90s, her elegant intensity was undiluted. In 1995's "Heat," she matches screen paramour Al Pacino in conveying operatic ennui; in 1996's "Romeo + Juliet," she delivers a bold take on the Lady Capulet role; and in 1997's "The Jackal," she has a grand time playing a tough-talking, gun-toting Russian soldier. More recently, she's appeared as an NSA advisor on the scifi series “The Vikings” (2005-2006) and as a mother with a drug problem in the indie "Self Medicated" (2005).

Vernon, John. Actor, 1932-2005. One of the most commanding bad guys of his era, Vernon played authoritarian roles with stern intensity, whether it was an opportunistic mayor in “Dirty Harry” (1971), a conflicted Confederate officer in “The Outlaw Josey Wales” (1976), or an unctuous college dean in “Animal House” (1978). The consistency of Vernon’s screen work speaks to a mostly lost tradition in which enterprising actors turned typecasting into career longevity, recognizing that the Hollywood mill always needs workers who can do a particular job on demand. It helped that Vernon was able to laugh at his own domineering image, whether subtly in “Animal House” or more broadly in the dopey spoof “I’m Gonna Git You Sucka” (1988). To see Vernon at his absolute sleaziest, check out the gruesome exploitation flick “Chained Heat” (1983), featuring the actor as a vile warden treating a women’s prison as his personal harem. Throughout his career, Vernon also contributed lively vocal performances to animated projects, for instance his recurring role as gangster Rupert Thorne in mid-’90s fave “Batman: The Animated Series.”

Videohound series. Visible Ink, the Michigan-based specialty press once responsible for the annually updated "Videohound's Golden Movie Retriever," expanded its movie-themed brand in the late '90s by launching a series of directories catering to niche audiences. "Videohound's War Movies" and "Videohound's Sci-Fi Experience" weren't groundbreaking, but some of the more adventurous titles in series were manna from heaven for their target audiences. "Videohound's Video Premieres" was an indispensable overview of straight-to-tape titles, covering everything from funky Steve Buscemi comedy to sleazy Shannon Whirry softcore; "Videohound's Groovy Movies" offered a breezy survey of psychedelic cinema, with informative sidebars and first-person accounts; "Videohound's Dragon" covered cult flicks from the Far East; and so on. Sadly, the last addition to the line was published in 2004, and since then, all books in the series have gone out of print. In other words, grab ’em if you find ’em.

“The Vikings” (1958). For a stretch in the late ’50s and early ’60s, Kirk Douglas hit the sweet spot again and again as a producer-actor, putting together film projects big enough to contain his outsized screen persona. For while Douglas was too flamboyant for intimate character pieces, he was unquestionably the right guy for adventures writ so large they verged on Wagnerian drama. “The Vikings” is an excellent case in point, because Richard Fleischer’s fleet-footed adventure moves from one memorable climax to another, going for the grand gesture at every turn. The cast is led by studio-era stalwarts Tony Curtis and Janet Leigh, who lay on the hokum as thick as they can, and by supporting player Ernest Borgnine, who revels in a role that lets him scream from entrance to exit. Even though the movie’s thoroughly silly, letting archetypal characters suffer mythic fates like getting eyes gouged out by falcons and being chewed to bits by ravenous wolves, it only rarely drifts into camp. There’s no gore, since it’s all in good fun, and the themes (betrayal, honor, redemption) are so monumental that the film feels like big-budget remake of an old-time movie serial. In fact “The Vikings” is so over-the-top macho that it should be ludicrous, but the script by regular Douglas collaborator Calder Willingham is so consistent and flavorful that it’s a pleasure to go on this particular ride into the land of make-believe.

Vince, Pruitt Taylor. Actor, b. 1960. Given his large build and the way a condition called nystagmus causes his eyes to quiver in their sockets, it’s unsurprising that Pruitt Taylor Vince’s roles run the short gamut from pathetic yokels to psychotic murderers. Yet even within the confines of typecasting, Vince has done years of extraordinary work. He scored an Emmy for a 1997 arc as a killer on the series “Murder One”; his mysterious character was the crux of the twisty 2003 thriller “Identity”; and the rube he played on “Deadwood” from 2005 to 2006 was memorably loathsome. A number of Vince’s most endearing roles find the actor personifying simple men with names like “Stinky Womack” and “Rub Squeers.” For prime examples, watch him invest surprising humanity into the dullards he plays in “Mississippi Burning” (1998) and “Nobody’s Fool” (1991). Or, to see him incarnating a rare benevolent character, watch for his brief appearance in the Sandra Bullock thriller “Bird Box” (2018). To date, Vince’s most expansive showpiece is the 1995 drama “Heavy,” in which he plays a shy sort with an eye for a comely waitress.

"Visions of Light: The Art of Cinematography" (1992). Pardon the failure of imagination, but the best word for this documentary is "illuminating." A loving, detailed exploration of the craft of cinematography, the picture uses breezy interviews and expertly chosen film clips to demonstrate why Michael Chapman's New York scenes have that special vibrancy, why Caleb Deschanel's exterior shots spark such envy in his peers, and why Gordon Willis, the shooter of the "Godfather" movies, is known as "The Prince of Darkness." Perhaps you've never stopped to check who photographed a movie and want an education. Or maybe you're a buff who knows the difference between Peter Biziou and Alan Daviau. Either way, chances are you'll be intoxicated by the stunning images and insightful talk that make this one of the most memorable documentaries ever made about cinema. If nothing else, you'll gain priceless insight into cinema technique when William A. Fraker explains how Roman Polanski made audiences tilt in their seats by repositioning a camera during the making of 1968's "Rosemary's Baby."

“The Visitor” (2008). Nominally part of the post-9/11 genre, Thomas McCarthy’s crisp, unsentimental character piece speaks to the themes of alienation and community that make urban life simultaneously terrifying and invigorating no matter the historical moment. Veteran character actor Richard Jenkins does remarkable work in his first on-screen leading role, playing Walter Vale, a widowed professor who finds a pair of illegal immigrants squatting in the Manhattan apartment he barely uses anymore. Realizing that Tarek and Zainab don’t have anywhere else to go, Walter lets them stay and then settles into an odd lifestyle cohabitating with the foreigners. Forced to see another life experience up close and personal, Walter is drawn to the vitality of Tarek’s career as a world-music drummer and incensed when Tarek is arrested by the U.S. government as a potential security threat. Jenkins’ performance takes flight when Walter becomes torn between his natural tendency to hide from life and his growing realization that the price of inaction in this instance might be higher than he can bear. One of the wonderments of this movie is that Jenkins’ turn isn’t a depressing study in angst; instead it’s a carefully crafted rendering of a man becoming himself at an age when opportunities for fundamental personal change should seem like distant memories.

"Wag the Dog" (1997). "It's a pageant!" This calming declaration, issued regularly by Hollywood smoothie Stanley Motss (Dustin Hoffman), captures the dry satire of this prescient movie about a U.S. president orchestrating a fake war to distract the press from his sexual indiscretions. Written nimbly by David Mamet and directed with Altman-esque looseness by Barry Levinson, the story meanders quite a bit, sometimes to its detriment, but the sequences that connect are so truthful and funny they seem extracted from a bizarre documentary. Robert De Niro, playing it mostly straight but still quite droll, is the mysterious government operative who recruits Motss to "produce" a fake war, but it's Hoffman—lampooning the shellacked confidence of Hollywood legend Robert Evans—who sets off the comic fireworks.

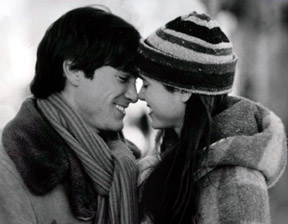

"Waking the Dead" (2000). Though sometimes too earnest for its own good, Keith Gordon's unusual love story in notable for including one of Jennifer Connelly's best performances prior to her Oscar-winning turn in "A Beautiful Mind" (2001). For this moody period piece, which is set in the '70s and '80s, Connelly plays a strident activist who falls in love with a budding politician (Billy Crudup). After Connelly's character is killed in Latin America, her spirit haunts the politician while he faces a series of ethical quandaries. Much of the love story is doled out in flashbacks, effectively dramatizing the impact the affair had on its surviving participant. Crudup and Connelly generate both heat and friction as the seemingly mismatched lovers, each adroitly depicting a different worldview.

"Waking the Dead" (2000). Though sometimes too earnest for its own good, Keith Gordon's unusual love story in notable for including one of Jennifer Connelly's best performances prior to her Oscar-winning turn in "A Beautiful Mind" (2001). For this moody period piece, which is set in the '70s and '80s, Connelly plays a strident activist who falls in love with a budding politician (Billy Crudup). After Connelly's character is killed in Latin America, her spirit haunts the politician while he faces a series of ethical quandaries. Much of the love story is doled out in flashbacks, effectively dramatizing the impact the affair had on its surviving participant. Crudup and Connelly generate both heat and friction as the seemingly mismatched lovers, each adroitly depicting a different worldview.

Walsh, M. Emmet. Actor, b. 1935. Customarily grumpy, disheveled, or bewildered (if not all three at once), Walsh is the quintessential character actor. His lumpy everyman look allows him to play everything from cops to hoboes to killers, and he’s just memorable enough that his appearance in a movie or TV show is like a serving of comfort food. Though occasionally featured on television, Walsh has done much of his significant work in features, first gaining notice in the late ’70s and early ’80s for grabbing oddball roles by the throat. In the grim drama “Straight Time” (1978), he’s a hard-hearted parole officer who gets a humiliating comeuppance; in the Steve Martin farce “The Jerk” (1979), Walsh is a wacko sniper taking potshots at people whose names he finds in a phone book; and in the sci-fi classic “Blade Runner” (1982), he’s the prototypical rumpled police boss trying to close a high-profile case fast. The actor enjoyed one of his biggest moments in 1987, when the Coen Brothers cast him as a scurrilous detective in their celebrated neo-noir “Blood Simple.” Then it was back to the ranks of below-the-title players, where his standard of quiet excellence has remained intact for decades.

“Walter Winchell.” Michael Herr has made important contributions to the movies, notably penning the narration of “Apocalypse Now” (1979), but the urbane scribe hasn’t been terribly prolific as a screenwriter. “Walter Winchell,” a unique 1990 novel extrapolated by Herr from his script for an unmade MGM biopic, explains why. As the author notes in his witty preface, he considered the piece “something ‘more’ than a screenplay” whereas his producers regarded it “as something less than a screenplay.” Both appraisals are true; the novel lacks the emotional and narrative propulsion of a movie, but compensates with staggering prose. As Herr presents a dreamlike montage about the life of famed gossip-monger Walter Winchell, the writer drops lines like this one: “The people inside look at him in that New York way, like they’ve seen it all before but they don’t want to be seeing it right now.” Herr’s descriptions are dry and acidic all at once, perfectly complementing Winchell’s bluster. And while it’s easy to picture some titanic actor chewing into Herr’s best scenes, the story is presented in such an impressionistic way that it really is better read than seen. As an object lesson in what a screenplay needs in order to flourish, and as a joyous exploration of all the literary things a movie can’t communicate, “Walter Winchell” is something special. Call it cinematic literature, complete with such resplendent but unfilmable screen directions as this one: “The glamour and glory of Walter Winchell’s epoch have reached full ripeness, and can only become overripe.”

Ward, Fred. Actor, b. 1942. Compact, wiry, and dark, Ward cut a memorable picture in the early '80s, when he gained marquee status with a string of roles as irascible types in varied movies. He played a violent redneck in "Southern Comfort" (1982), a squirrelly astronaut in "The Right Stuff" (1983), a disturbed vet in "Uncommon Valor" (also 1983), a shifty drifter in "UFOria" (1985), and so on. Yet even when cloaked in such unsavory characters, Ward found ways to let his folksy charm shine, probably never more so than in "Tremors" (1990) and its 1996 sequel. As an optimistic but not particularly bright monster hunter, Ward is laugh-out-loud funny. Philip Kaufman adventurously cast Ward as salacious novelist Henry Miller in "Henry & June" (1990), which offered the actor a rare opportunity to portray not only an educated character but a sensual one, and he's memorably provocative in the part.

Warden, Jack. Actor, 1920-2006. Though his career included more than 150 appearances in films and TV shows spanning the entire second half of the twentieth century, Warden is frozen in my mind circa the 1970s, when his expressive scowl and slow-burn delivery turned exasperation into irresistible entertainment. Whether playing a crass adulterer in "Shampoo" (1975), an impassioned editor in "All the President's Men" (1976), a befuddled football coach in "Heaven Can Wait" (1978), or a judge-turned-defendant in "...And Justice for All" (1979), Warden was a marvel of precision and modulation, finding just the right rhythms to underline dramatic climaxes and emphasize comic high points. With his brassy voice and bearish appearance, Warden spent the '70s conveying an everyman quality that belied the kinetic energy of his acting. His efforts were amply rewarded, with an Emmy for his turn as a coach in the telefilm "Brian's Song" (1971) and Oscar nominations for "Heaven Can Wait" and "Shampoo." Along with his more nuanced work, Warden savored opportunities to go gleefully over the top, particularly when playing crusty frontier types in such larks as "The White Buffalo" (1977). Among his notable credits outside the '70s are a string of live TV dramas in the '50s; "12 Angry Men" (1957) and "The Verdict" (1982), both for director Sidney Lumet; and his feisty appearances in the lucrative "Problem Child" movies of the '90s.

Warner, David. Actor, b. 1941. With his long face and imposing build, British actor Warner often seems taller than his height of six feet and two inches, an effect compounded by his frequent appearances as domineering authority figures. Though usually cast for his ability to portray menacing characters, Warner is equally effective when asked to convey nobility. Originally a stage actor, he appeared in a few notable pictures in the late '60s—he's a gorilla-obsessed doctor in "Morgan" (1966) and a brutally pragmatic general in "The Fixer" (1968)—before making an indelible impression as a troubled man-child in Sam Peckinpah's "Straw Dogs" (1971). Warner then endeared himself to genre fans by playing a happily sadistic Jack the Ripper in "Time After Time" (1979). The impression created by that role was cemented by turns as a hilariously malevolent superbeing in "Time Bandits" (1981) and as a computerized baddie in the early CGI experiment "Tron" (1982). Warner's subsequent credits continue the eclectic pattern, with roles in everything from quiet British dramas to assorted iterations of "Star Trek." His princely bearing and musical diction as distinct as ever, Warner played colorfully named henchman Spicer Lovejoy in "Titanic" (1997). More recently, his film/TV work has broadened to include numerous voice performances, and Warner essayed yet another colorful aristocrat by taking over the role of Admiral Boom in "Mary Poppins Returns" (2018), a sequel 54 years in the making.

“The Warriors” (1979). With its comic-book visuals, hypnotic editing, and stylized violence, Walter Hill’s most intoxicating movie feels more like pop art than an exploitation picture. Adapted from a Sol Yurick novel, the piece presents a nightmarish vision of New York City that’s populated by street gangs who use any means necessary protect their turf. When a visionary leader is killed in the Bronx during his attempt to organize the gangs, a scrappy Coney Island outfit called the Warriors gets framed for the murder. The hard-luck bruisers then have to fight their way across the city with every gang in their path out for blood, leading to battles with crews like the Furies, who wear baseball uniforms and creepy makeup while bashing their opponents with wooden bats. Hill’s storytelling is muscular and brazen, with Barry DeVorzon’s pounding music driving one audacious sequence after another while Andrew Laszlo’s sleek photography captures the battered grandeur of New York after dark. Fair warning, however: While appropriate for the story’s milieu, the main characters’ crude attitudes toward women and the LGBTQ community have aged badly.

"The Weather Man" (2005). A smart movie in search of a protagonist worthy of its virtues, this was one of the oddest studio releases of 2005, simply because it flies in the face of everything the studios generally issue. It's small, dark, cerebral, and quiet. Nicolas Cage, reining in his outsized persona, plays a depressed meteorologist dealing with a hostile ex-wife (Hope Davis), a condescending dad (Michael Caine), an insecure daughter (Gemmenne de la Peña), and success of which he feels undeserving. Individual bits are beautifully executed and the performances are top-notch across the board, but the movie's unsatisfying because the lead character never seems interesting enough to warrant this kind of attention. Still, as a bright beacon representing the kind of adult, character-driven movies Hollywood rarely makes anymore, "The Weather Man" is encouraging. And even with its protagonist problem, it's quite entertaining, if only for the cringe-worthy significance it attaches to the previously unfamiliar phrase "camel toe."

Webber, Robert. Actor, 1924-1989. It’s fitting that one of Webber’s only leading roles was in a 1965 British thriller called “Hysteria,” because some of his greatest onscreen moments occurred when he got, well, hysterical. A solidly built ex-Marine who trained on Broadway and came up through early television, Webber played a broad variety of slimy types, from the lecherous yuppie of “The Sandpiper” (1965) to the gay thug of “Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia” (1974), and so on. The die was pretty much cast from his first major role, as a superficial ad man in “12 Angry Men” (1957); from that point on, Webber got the call whenever a movie or TV show needed an unscrupulous everyman. Though quite effective in his many villainous parts, Webber was perhaps most gifted as a comic actor. He was terrific in a trio of Blake Edwards farces, culminating in his explosive turn as publicist with unreliable excretory functions in “S.O.B.” (1981). Toward the end of his career, Webber joined the brainy series “Moonlighting” for a recurring role as the father of Cybill Shepherd’s character. The year after his last appearance on the show, he succumbed to Lou Gehrig’s Disease.

Weller, Peter. Actor/filmmaker/academic, b. 1947. Weller achieved stardom with 1987's "RoboCop," imbuing the titular lawman with pathos that belied the character's mechanical nature, and that picture led to a long run of gritty and offbeat movies. In pictures ranging from the sleazy neo-noir "Cat Chaser" (1990) to the sci-fi actioner "Screamers" (1995), Weller portrays world-weary types who exude toughness and intelligence. And though he plays it comparatively straight on occasion, as in the social satire "The New Age" (1994), his bread-and-butter gigs remain heavies and officious types. Yet Weller's signature part, in addition to being his most unusual, may still be his leading turn in "The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension" (1984), a cult-movie take on Saturday-afternoon serials starring Weller as a musician/scientist/surgeon/commando. Weller not only demonstrates each of the character's specialties, but he multitasks with cool confidence. That's appropriate, because in addition to acting, Weller has written and/or directed several projects, occassionally teaches college courses, and holds a Ph.D. in art history.

Wexler, Haskell. Filmmaker/lefty, 1926-2015. A world-class cinematographer whose contentious personality might be the reason his credit appears on so few truly great films past his heyday in the '60s and '70s, Wexler gave a huge variety of pictures a luminous glow of rare authenticity. Although equally adept at capturing tense imagery (as in 1966's "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf"), Wexler stands out in my mind for the naturalistic feel of "Bound for Glory" (1976), "Coming Home" (1978), and "Matewan" (1987). His elegant shooting gave these tough, socially conscious stories the dignity and grit they needed. It helped tremendously that the man suited the work—Wexler enjoyed (or endured) decades of notoriety for his passionate left-wing politics. His most important directorial credit, "Medium Cool" (1969), is the edgy docudrama filmed, in part, at the 1968 Democratic convention. The moment when a crew member shouts "Haskell, it's real!" during a tear-gas assault is about as meta as it gets. Long a compatriot of fellow lefty John Sayles, Wexler was the subject of the unflattering documentary "Tell Them Who You Are" (2004), in which director Mark Wexler tried to cut through his father's combative personality in order to find the man behind the rabble-rouser mystique.

Whaley, Frank. Actor/filmmaker, b. 1963. After making his mark as a fresh-faced leading and supporting player in a broad variety of movies in the late '80s and early '90s—playing Matthew Broderick's skeptical roommate in "The Freshman" (1989), getting upstaged by Jennifer Connelly's cleavage in "Career Opportunities" (1991), surviving his appearance in the musical "Swing Kids" (1993)—Whaley found a place in more serious-minded pictures. Possessing a likeable New York City swagger even though he's actually from Syracuse, Whaley scored as ill-fated student Brad in "Pulp Fiction" (1994) and then held his own against a scenery-chewing Kevin Spacey in the acidic Hollywood satire "Swimming With Sharks" (also 1994). Appearing steadily, if not with great consequence, in films and television since then, Whaley began making his own movies with the 1999 period drama "Joe the King." A reliable presence whose appearances usually hinge on his impeccable comic timing, Whaley is beyond overdue for a breakout part that cements him in the public imagination. Until then, he’ll keep excelling in featured parts, whether as a corrupt detective in the Marvel/Netflix show "Luke Cage" (2016-2018) or as a high-roller who gets suckered by strippers in "Hustlers" (2019).

Whaley, Frank. Actor/filmmaker, b. 1963. After making his mark as a fresh-faced leading and supporting player in a broad variety of movies in the late '80s and early '90s—playing Matthew Broderick's skeptical roommate in "The Freshman" (1989), getting upstaged by Jennifer Connelly's cleavage in "Career Opportunities" (1991), surviving his appearance in the musical "Swing Kids" (1993)—Whaley found a place in more serious-minded pictures. Possessing a likeable New York City swagger even though he's actually from Syracuse, Whaley scored as ill-fated student Brad in "Pulp Fiction" (1994) and then held his own against a scenery-chewing Kevin Spacey in the acidic Hollywood satire "Swimming With Sharks" (also 1994). Appearing steadily, if not with great consequence, in films and television since then, Whaley began making his own movies with the 1999 period drama "Joe the King." A reliable presence whose appearances usually hinge on his impeccable comic timing, Whaley is beyond overdue for a breakout part that cements him in the public imagination. Until then, he’ll keep excelling in featured parts, whether as a corrupt detective in the Marvel/Netflix show "Luke Cage" (2016-2018) or as a high-roller who gets suckered by strippers in "Hustlers" (2019).

"When Night Is Falling" (1995). While the entwined lovelies on the poster for this Canadian romance promise soft-focus lesbian erotica, which is found in ample measure, Patricia Rozema's dreamy, unabashedly arty love story is after a lot more than raising audience temperatures. By telling the not-unfamiliar story of an uptight hetero character swept away by the affections of an uninhibited homosexual, Rozema advances her gently politicized agenda of enlightening the ignorant and intolerant. Yet by marrying that material to a rarefied milieu, in this case a Cirque de Soleil-type highbrow circus, Rozema draws an interesting analogy between making love and making art. The film's most ambitious sequences succeed in spite of themselves; Rozema tries a little too hard to conjure magic, seemingly lacking confidence in the tender textures she captures with her keen eye. Even when the film's credibility is stretched thin, it offers many winning qualities, not the least of which is beguiling leading lady Pascale Bussières.

“When the Legends Die” (1972). A simple character piece that sometimes approaches the tragic poetry of a Sam Shepard story, this contemporary Western features a surprisingly persuasive Frederic Forrest as Tom Black Bull, an 18-year-old Ute Indian roped into the world of rodeo riding by a conniving rancher named Red (Richard Widmark). Quickly realizing that he’s just the latest hunk of meat trotted out for the amusement of the bloodthirsty masses, Tom evolves into “Killer” Tom Black after driving several horses to their demise during brutal rides. He also outgrows Red’s heartless stewardship, becoming disgusted at Red’s drunkenness, debauchery, and deceitfulness. While ostensibly one of the many bleeding-heart movies about Native Americans clashing with crass modern society that Hollywood cranked out in the early ’70s, “When the Legends Die” ultimately works as its own story by crafting vivid characters who both personify and exceed the parameters of the archetypes they represent. And while Forrest gives the piece its soul, Widmark makes a strong impression by contributing a characteristically unsentimental but unusually lived-in performance.

“White Dog” (1982). Samuel Fuller’s controversial movie about a dog trained to attack black people is a disturbing blend of social-commentary content and horror-movie style. Young actress Julie (Kristy McNichol) hits a stray German shepherd and adopts the injured dog, then bonds with the animal when he saves her from a rapist who invades her home. In a horrific incident at her job, however, she watches the dog attack and nearly kill a black woman, so Julie reaches out to a crusty animal trainer, Carruthers (Burl Ives). Though he recommends she have the dog put down, Julie resists because she owes the animal her life. Then Carruthers and his black colleague, Keyes (Paul Winfield), realize the animal is a “white dog,” bred and trained by a vicious racist. Keyes is obsessed with trying to recondition white dogs, so once all the plot elements are in place, the story becomes a ticking-clock narrative about whether Keyes can break the dog before something awful happens. Fuller and his team go down every horrific avenue suggested by the premise, hammering the film’s themes even when story elements stretch believability to the limit. And while the filmmaking is unabashedly ham-fisted, three elements add immeasurably to the movie’s impact: Ennio Morricone’s score is frightening and mournful; Winfield gives a movingly committed performance, filling scenes with anguish even when he’s saddled with preachy monologues; and the ending is a shocker. Fuller’s last movie, “White Dog” was never properly released in U.S. theaters because of false rumors it was a racist tract, but its cult audience grew until the Criterion Collection finally issued the movie on DVD in 2008.

"The Whole Wide World" (1996). Based on a memoir by Novalyne Price about her Depression-era friendship with pulp writer Robert E. Howard, the creator of Conan the Barbarian and other characters, this muted drama is a duet between Renee Zelwegger (as Price) and Vincent D'Onofrio (as Howard). Presenting a relationship that never blossoms into the romance it might have under different circumstances, the movie is something more nuanced than a story of unrequited love—it's a story of undefined love. Schoolteacher Price is initially startled by tortured artist Howard, who seems incapable of blending into polite society due to his abrasive personality and wild imagination. But Dan Ireland's gently probing movie captures the ways in which these very different people find common ground as intellectuals and, to the degree that Price can match Howard's maverick behavior, individualists. Though overshadowed by her starmaking turn in the same year's "Jerry Maguire," Zellweger's performance as Price is deeply affecting, and D'Onofrio is fearsome, particularly when regaling Price with a description of his brutal creation Conan.

“The Wild Angels” (1966). Touched with a bit of counterculture magic, Roger Corman’s influential drama set the template for countless subsequent biker pictures while also capturing the ephemeral qualities of a cultural moment. Peter Fonda stars as Heavenly Blues, the charismatic leader of the Venice, California, chapter of the Hell’s Angels, and Bruce Dern plays Loser, one of his most beloved riding buddies. The plot is so simple that it’s almost aimless, with the Angels hassling civvies and in turn getting hassled by the man. Furthermore, every trope of the genre is present: violent rumbles, raunchy parties, copious drug use, stoner speechifying. In its way quite unflinching, the movie boasts an insightful script (credited to Corman regular Charles B. Griffith but heavily rewritten by then-newcomer Peter Bogdanovich), authentic flavor stemming from the use of real Hell’s Angels as extras, and lush widescreen cinematography. One of those movies that belies Corman’s rep as the “King of the Bs” by offering moments of genuine artistry, it’s an exploitation picture with something provocative beneath the sex-and-violence sheen.

"The Wild Geese" (1978). A pulpy mercenary yarn filmed in Africa and England, "The Wild Geese" offers lip service to issues of racism and political opportunism, but really takes wing (no pun intended) when its cast of aging Brits engages in loose interplay. Richard Burton, quite believable as a lush, joins Richard Harris and a Bond-era Roger Moore as the leaders of a fighting squad hired to liberate a Nelson Mandela-style leader from a heavily guarded African prison. Complications ensue, as do personal turnabouts including the softening of fellow merc Hardy Kruger's prejudice. The men-on-a-mission aspect of the picture gets off to a slow start, but the seasoned players imbue the goings-on with swagger and, owing to their years, an inherently elegiac quality. While the emotionally manipulative climax is unlikely to catch many viewers by surprise, I must confess that it got to me the first time I saw the picture—and, for that matter, during many subsequent viewings. Another distinguishing characteristic is the soaring Joan Armatrading theme song, not exactly the sort of thing one expects to encounter in a macho adventure picture.

“Wild Man Blues” (1997). Documentarian Barbara Kopple was given extensive access to the famously private Woody Allen when the filmmaker took his hobby on the road for a European tour of old-school New Orleans jazz. The resulting documentary, “Wild Man Blues,” isn’t so much about music as it is about Allen moving through the world with his companion, Soon-Yi Previn, which is fascinating because the couple’s past is fraught with controversy. Since Allen spends much of his offstage time in this doc spouting one-liners, it’s hard to say whether we’re seeing truth or something manufactured, so it’s interesting to parse the movie for moments when the protagonist seems genuinely unguarded. Despite a fair amount of dodgy musicianship, the extended concert sequences are enjoyable because the famously joy-averse Allen seems happy playing his clarinet, and the scenes of Allen’s entourage walking through Europe reveal the peculiar existence of the unimaginably famous: Allen’s forever surrounded by mobs of fans, photographers, and sycophants. The real prize in the movie is the final scene, during which Allen returns from his European trek with an armload of trophies that he delivers, like all of his prizes, to his monumentally dissatisfied parents. It’s a revelatory moment that says volumes about how Allen evolved.

Wilhoite, Kathleen. Actor/musician, b. 1964. Expressive, versatile, vulnerable, and natural, Wilhoite has given credibility to a rainbow of roles in films and television from the early '80s onward. First appearing as Phoebe Cates' sidekick in the icky sex comedy "Private School for Girls" (1983), Wilhoite quickly found a niche in quirky character parts, only occasionally playing leads in telefilms and unremarkable features. One tends to stumble onto Wilhoite's performances, as her presence is rarely employed as a selling point, but such discoveries are almost always rewarding—even in routine entertainments like the luridly titled 1993 telefilm "Broken Promises: Taking Emily Back," Wilhoite plays scenes with imagination, power, and authenticity. In fact, one of her most distinctive early appearances was as Charles Bronson's unlikely cohort in an otherwise forgettable action flick called "Murphy's Law" (1986). She enjoyed one of her showiest parts as unbalanced Chloe Lewis on TV's "ER," appearing intermittently on the show from 1994 to 2002. Other series on which she has played recurring characters include "L.A. Law" (from 1993 to 1994) and "The Gilmore Girls" (from 2004 to 2007). In 1998, she released her first album as a singer-songwriter, displaying the beautifully aching colors in her voice throughout the lovely "Pitch Like a Girl." Another album, "Shiva," followed in 2000.

Wilhoite, Kathleen. Actor/musician, b. 1964. Expressive, versatile, vulnerable, and natural, Wilhoite has given credibility to a rainbow of roles in films and television from the early '80s onward. First appearing as Phoebe Cates' sidekick in the icky sex comedy "Private School for Girls" (1983), Wilhoite quickly found a niche in quirky character parts, only occasionally playing leads in telefilms and unremarkable features. One tends to stumble onto Wilhoite's performances, as her presence is rarely employed as a selling point, but such discoveries are almost always rewarding—even in routine entertainments like the luridly titled 1993 telefilm "Broken Promises: Taking Emily Back," Wilhoite plays scenes with imagination, power, and authenticity. In fact, one of her most distinctive early appearances was as Charles Bronson's unlikely cohort in an otherwise forgettable action flick called "Murphy's Law" (1986). She enjoyed one of her showiest parts as unbalanced Chloe Lewis on TV's "ER," appearing intermittently on the show from 1994 to 2002. Other series on which she has played recurring characters include "L.A. Law" (from 1993 to 1994) and "The Gilmore Girls" (from 2004 to 2007). In 1998, she released her first album as a singer-songwriter, displaying the beautifully aching colors in her voice throughout the lovely "Pitch Like a Girl." Another album, "Shiva," followed in 2000.

Williams, Treat. Actor, b. 1951. Born a Connecticut blueblood, Williams traipsed through an odd assortment of roles—like that of a charismatic hippie in “Hair” and that of a hot-tempered solider in “1941” (both 1979)—before crafting his complicated portrayal of real-life cop Daniel Ciello in Sidney Lumet’s “Prince of the City” (1981). Williams gave a strong performance that suffered for comparisons to Al Pacino’s work in Lumet’s similar but superior “Serpico” (1973). Then, compounding his bad luck, Williams foundered in a series of unfortunate flops. Even with terrific notices for his turn as a predatory stud in “Smooth Talk” (1985), he still hadn’t found his moment. Years later, after a particularly fallow stretch, Williams gave a nervy turn as Michael Ovitz in “The Late Shift” (1996), an otherwise routine telefilm; showing grit by satirizing one of the most powerful men in show business and also giving a performance of smoldering confidence, Williams earned an Emmy nomination and repositioned himself as a character actor of considerable skill. A run of small parts in big movies followed before television again proved Williams' professional salvation when the role of sensitive doctor Andy Brown in the WB series “Everwood” (2002-2006) made him something of a household name, if only for a brief period of time. In recent years, Williams has done respectable work while traveling the vagabond path of the featured player in various films and TV shows.

Williamson, Nicol. Actor, 1936-2011. Possessed, by all accounts, of a singularly difficult personality, it's a wonder Williamson had the patience to commit as many memorable performances to film as he did before withdrawing from the medium in 1997. (Given that his last appearance was in the insipid superhero flick "Spawn," can you blame him?) A ferocious stage performer whose takes on various Shakespearean characters established his reputation in the '60s, Williamson prowled through scenes with feline grace, his mellifluous deliveries and wry expressions supercharging strong scenes with nuance and gifting poor ones with much-needed gravitas. Appearing largely in European films at the beginning of his career, Williamson re-created one of his key stage roles in Tony Richardson's 1969 film of "Hamlet." He also interpreted "the Scottish play" for a 1983 telefilm of "Macbeth." Perhaps befitting his classical background, Williamson's best screen appearances involve characters rooted in legend—Robin Hood's trusty foil Little John in "Robin and Marian" (1976), a drug-addled Sherlock Holmes in "The Seven Per-Cent Solution" (also 1976), a mischievous Merlin the Magician in "Excalibur" (1981). Also noteworthy is his incendiary leading role in "The Reckoning" (1970), as a businessman who indulges savage appetites, and his wonderfully bitchy supporting performance in "The Wilby Conspiracy" (1975), as a corrupt South African policeman with a penchant for vicious sarcasm.

Wilson, Scott. Actor, 1942-2018. This criminally underappreciated actor began his career playing criminals, grafting his Atlanta-bred drawl and hangdog features to a bit part as a crook in "In the Heat of the Night" and to a second lead as a doomed killer in "In Cold Blood" (both 1967). Working sporadically through the '70s, often in thankless parts as rednecks or thugs or both, Wilson found a patron in 1980, when writer-director William Peter Blatty gave him an unusual costarring role in "The Ninth Configuration." Playing an astronaut whose refusal to go to the moon lands him in an asylum, Wilson is funny, intense, and heartbreaking. Sadly, Blatty's directorial career stalled, and he was only able to cast Wilson once more, in a terrific featured role as a nervous shrink in 1990's "The Exorcist III." Throughout his career, Wilson occupied the peculiar niche of the character actor, sometimes shining briefly in big movies, sometimes offering the most winning moments in small ones. Luckily for audiences, he enjoyed a boom in later life, appearing as an unfortunate soul in the serial-killer drama "Monster" (2003), a hilariously taciturn dad in the well-received indie "Junebug" (2005), and as the casino-owner father of Marg Helgenberger's character on "CSI: Crime Scene Investigation." From 2011 to 2018, Wilson beautifully essayed the role of doomed farmer Hershel Greene on AMC's zombie hit "The Walking Dead," lending notes of conscience and soulfuness to the show’s signature carnage.

Winfield, Paul. Actor, 1941-2004. One of the most versatile players to gain prominence in the '70s, Winfield scored an Oscar nomination for the earnest sharecropping drama "Sounder" (1972), then spent the next thirty years marking time in character roles while leading parts in broadly seen films mostly evaded him. Among the few projects that gave him room to command the screen were the 1977 telefilm "Green Eyes," with Winfield as a vet who returns to Vietnam in order to claim the child he fathered, and the 1978 telefilm "King: The Martin Luther King Story," with Winfield as the civil-rights leader. After a number of years playing intense types, including several disillusioned veterans, in such diverse pictures as "Gordon's War" (1973) and "Twilight's Last Gleaming" (1977), Winfield found steady work playing authority figures in the '80s and beyond, endearing himself to fantasy fans with memorable turns in "Star Trek II" (1982) and "The Terminator" (1984). Working steadily in projects of diminishing quality until his premature death at age 62, Winfield made his last screen appearance in a 2003 telefilm remake of his breakthrough movie, "Sounder."

"Wings of Desire" aka "Der Himmel über Berlin" (1987). "I can't see you, but I know you're there." That line, spoken by Peter Falk in his persuasive turn as Peter Falk, sums up the faith that cowriter-director Wim Wenders explores in this one-of-a-kind dreamscape about angels watching over the souls of divided, Cold War-era Berlin. Bruno Ganz plays Damiel, a world-weary seraphim whose routine of eavesdropping on Germans' pain is portrayed in gossamer black-and-white photography, soaring camera moves, and a wall of sound comprising the voices that cry out for his sympathy. When Damiel becomes enamored of a sad circus performer (Solveig Dommartin), he wrestles with giving up immortality for love in the real world. Wenders is absolutely the right guy to present this existential crisis, approaching the story through visual and verbal poetry, playful cinematic devices, and soulfulness. The climactic sequences of Damiel making his decision are deeply moving, and the film is studded with unforgettable moments—gloomy singer Nick Cave's interior monologue, Falk's revelation of a personal secret, a convergence of angels inside a crowded library. As for the simplified American remake "City of Angels" (1998), it's neither as bad nor as good as it might have been.

"Wings of Desire" aka "Der Himmel über Berlin" (1987). "I can't see you, but I know you're there." That line, spoken by Peter Falk in his persuasive turn as Peter Falk, sums up the faith that cowriter-director Wim Wenders explores in this one-of-a-kind dreamscape about angels watching over the souls of divided, Cold War-era Berlin. Bruno Ganz plays Damiel, a world-weary seraphim whose routine of eavesdropping on Germans' pain is portrayed in gossamer black-and-white photography, soaring camera moves, and a wall of sound comprising the voices that cry out for his sympathy. When Damiel becomes enamored of a sad circus performer (Solveig Dommartin), he wrestles with giving up immortality for love in the real world. Wenders is absolutely the right guy to present this existential crisis, approaching the story through visual and verbal poetry, playful cinematic devices, and soulfulness. The climactic sequences of Damiel making his decision are deeply moving, and the film is studded with unforgettable moments—gloomy singer Nick Cave's interior monologue, Falk's revelation of a personal secret, a convergence of angels inside a crowded library. As for the simplified American remake "City of Angels" (1998), it's neither as bad nor as good as it might have been.

"Winter Kills" (1979). Arguably the strangest entry into the '70s conspiracy-thriller sweepstakes, this audacious adaptation of a novel by Richard Condon ("The Manchurian Candidate") concerns the lingering repercussions of a JFK-style assassination. Jeff Bridges plays the slain leader's haunted brother, and John Huston plays the patriarch of Bridges' political family. In the convoluted plot, Bridges starts investigating his brother's death, which irks power-mad Huston and makes Bridges a target of the conspirators. Bursting with imagination and style, writer-director William Richert's movie goes way over the top at regular intervals, tying itself into narrative knots and letting outlandish characters have the run of the place. That's the fun of "Winter Kills," though—intentionally or not, it's both a dead-serious political thriller and a wacky send-up of the genre. The cast is loaded with unfailingly entertaining players, with Bridges at his most angsty and Huston at his most Noah Cross wicked; Sterling Hayden, Toshiro Mifune, Anthony Perkins, and an uncredited Elizabeth Taylor join in the dark fun. Ace shooter Vilmos Zsigmond gives the picture high gloss, and leading lady Belinda Bauer brings considerable sexual heat to her movie debut.

Wise, Ray. Actor, b. 1947. With those intense eyes blazing from beneath one of the most pronounced brows in American cinema, Wise has lived up to his surname in recent years, sliding into steady work as authority figures in movies and television. Yet in many of his most interesting appearances, he conveys quivering neuroses, palpable fear, and even outright insanity. Showing up in routine parts throughout the '70s and '80s, from his five-year stint on the soap "Love of Life" (1970-1976) to his warm turn as a Depression-era dad in "The Journey of Natty Gann" (1985), Wise went cuckoo to quite memorable effect as pathological paterfamilias Leland Palmer in David Lynch's series "Twin Peaks" (1990-1991). His authority-figure period followed, with Wise playing everything from an ill-fated newsman in "Good Night, and Good Luck." (2005) to an inept veep on the 2005-2006 season of “24.” Then Wise went dark again, this time with a comic twist, by playing a chipper version of Satan in the lauded but short-lived series “Reaper” (2007). Shifting gears, the actor dialed down the menace for his 2015-2020 run as an amiable neighbor on the sticom “Fresh off the Boat,” though his dark onscreen past resurfaced when he essayed the Leland Palmer role once more for the long-gestating third season of “Twin Peaks” in 2018.

“Witchfinder General” aka “The Conqueror Worm” (1968). Vincent Price plays one of his most credible latter-day roles in this harrowing drama about a vicious opportunist who rampages through 17th-century Britain, staging sensational inquests in his “righteous” search for witches. The picture details every sleight-of-hand trick the witchfinder uses to arrive at convenient results, and the capricious ways in which the inquisitor decides who lives and dies are chilling. The loathsome character’s evil ways eventually come back to haunt him, and while it isn’t necessarily fun to watch the villain get his due, the whole story is vivid and engrossing. One of the reasons this movie has gained cult status over the years—aside from Price’s presence and the imprimatur of schlock distributors American International Pictures, who released the movie in the U.S.—is that it was the last film directed by promising Michael Reeves, who died at the shocking age of 25. Thank AIP for the goofy alternate title, culled from an Edgar Allen Poe poem; they ditched the original moniker to disingenuously align Reeves’ picture with the various Poe flicks starring Price.

“Without a Trace” (1983). Stanley R. Jaffe obviously picked up a thing or two while producing such celebrated movies as “The Bad News Bears” (1976) and “Kramer vs. Kramer” (1978), because in his sole feature as a director he exhibits uncommon restraint and taste. A story of wrenching simplicity, this soft-spoken drama concerns a divorced mother, Susan (Kate Nelligan), whose six-year-old boy disappears somewhere in the two Manhattan blocks between his home and his school. Days, weeks, and finally months pass in which Susan refuses to believe the worst has come to pass, and in which a caring police detective (Judd Hirsch) hardens himself despite the fact that his own son is the same age as the missing child. Jaffe and screenwriter Beth Gutcheon (adapting her own novel) meticulously document the impact of the crisis on Susan’s tightly wound character, and one fascinating thread of the picture is the contempt that “normal” people have for Susan’s unwillingness to crumble into incoherent despair. The ending of the picture sharply divided critics, oddly echoing the fictional world’s misinterpretation of Susan: Like the people who can’t understand a mother who doesn’t weep every moment her child is endangered, critics couldn’t understand a missing-persons story in which the resolution is not necessarily the point.

"Without Limits" (1999). The mythos surrounding Robert Towne, beloved by movie geeks as the shambolic poet who pens the killer scene that saves a movie, raises unreasonable expectations whenever he directs, so anyone expecting this biopic about driven '70s Olympic athlete Steve Prefontaine to be a work of unrestrained genius will be disappointed. But as an underdog sports movie with more grit and smarts than most such pictures, "Without Limits" is rewarding. An intense Billy Crudup blazes through the movie without ever pandering for viewers' sympathy. His Prefontaine comes off as a self-centered son of a bitch, which makes the character quite credible as a fierce competitor. Donald Sutherland is given plenty of chances to steal the movie as Prefontaine's imaginative, hard-driving coach; that Sutherland plays the part broadly yet still defers to Crudup's performance is an indication of the movie's serious-mindedness.

"Wolfen" (1981). A horror story about super-intelligent canines adapted from a novel by Whitley Streiber ("The Hunger"), the sole fiction feature from "Woodstock" helmer Michael Wadleigh has beguiling atmosphere thanks to cinematographer Gerry Fisher and composer James Horner. Wadleigh and Fisher, abetted by Steadicam guru Garrett Brown, send their cameras whirling and prowling through a variety of arresting New York City locations, from the tops of suspension bridges to the bowels of Bronx slums. Horner, showing off big time at the beginning of his long career, utilizes many effective tropes that recurred in his subsequent score for 1982's "Star Trek II"; even during rare sequences when the the visuals underwhelm, Horner's score creates genuine excitement. Perhaps most importantly, the movie is filled with wonderful actors, from leads Albert Finney, Gregory Hines, and Diane Venora to supporting players Tom Noonan, Edward James Olmos, and Dick O'Neill. The caveats? Streiber's story is tantalizing but unsatisfying, and Wadleigh frequently gets lost in his meticulously crafted imagery. The result is a movie that should fly by on sheer talent and gusto, but instead lumbers. Still, it's well worth perusing for its myriad effective elements, not least of which is the offbeat climax.

“The Wolf Man” (1941). “Even a man who is pure in heart and says his prayers by night, may become a wolf when the wolfbane blooms and the autumn moon is bright.” The genius of Curt Siodmak’s script for this Universal Studios monster-movie classic, which introduced that memorable verse into the popular culture, is the illusion it creates of a legend that’s been around forever. Telling the sad tale of Larry Talbot (Lon Chaney Jr.), whose idyllic life is interrupted by a bout of lycanthropy, “The Wolf Man” perfected the tragic-monster formula that was later emulated by a zillion other flicks about people tormented by supernatural transformations. There’s also a deeper level of significance because Chaney, whose performance seethes with anguish, was himself tormented; initially unwilling to follow in the footsteps of his father, schock-cinema icon Lon Chaney Sr., the man born Creighton Chaney accepted the family mantle, and all its attendant baggage, only when attempts to make a name for himself failed. Yet all of that unfolds behind the scenes—onscreen, “The Wolf Man” is as jaunty as an Errol Flynn swashbuckler, and the supporting cast is terrific, especially Maria Ouspenskaya as a fortune-teller and Claude Rains as Larry’s forlorn father. On top of all that, there’s Jack Pierce’s endlessly imitated werewolf makeup and those old-school transformation scenes, achieved with meticulously planned dissolves. Silly and touching at the same time, “The Wolf Man” is top-shelf Hollywood hokum.

Woodard, Alfre. Actor, b. 1952. Maybe it's that laugh. Quite often when in the midst of a heavy dramatic scene, Woodard releases a gentle chuckle filled with as much surprise as amusement. These moments feel completely spontaneous, and they speak volumes about how small a role joy plays in the lives of many of her characters. Woodard has a unique gift for capturing the unpredictable rhythms of life, and though she's just fine in light roles, she's mesmerizing when incarnating haunted characters. In "Passion Fish" (1992) and "Down in the Delta" (1997), she conveys the day-to-day aches of those living with addiction, her tiny frame rocking with anger one minute and quaking with shame the next. Even in piffle like "Star Trek: First Contact" (1996), she crafts vivid moments, such as the bit of her earthbound character getting her first awestruck look at outer space. Much of Woodard's most celebrated work has been on television, and she's got four Emmys to show for her efforts. She's had notable roles on "Hill Street Blues," "St. Elsewhere," "Desperate Housewives," and many other series, as well as in such acclaimed telefilms as 1997's Tuskegee Airmen drama "Miss Evers' Boys." More recent work, all of it up to Woodard’s usual high standards, includes a surprisingly dimensional characterization as a murderously corrupt politician on the Marvel/Netflix series “Luke Cage” (2016-2018) and a heavy role as a warden forced to consider death-penalty issues in “Clemency” (2019).

Woodard, Alfre. Actor, b. 1952. Maybe it's that laugh. Quite often when in the midst of a heavy dramatic scene, Woodard releases a gentle chuckle filled with as much surprise as amusement. These moments feel completely spontaneous, and they speak volumes about how small a role joy plays in the lives of many of her characters. Woodard has a unique gift for capturing the unpredictable rhythms of life, and though she's just fine in light roles, she's mesmerizing when incarnating haunted characters. In "Passion Fish" (1992) and "Down in the Delta" (1997), she conveys the day-to-day aches of those living with addiction, her tiny frame rocking with anger one minute and quaking with shame the next. Even in piffle like "Star Trek: First Contact" (1996), she crafts vivid moments, such as the bit of her earthbound character getting her first awestruck look at outer space. Much of Woodard's most celebrated work has been on television, and she's got four Emmys to show for her efforts. She's had notable roles on "Hill Street Blues," "St. Elsewhere," "Desperate Housewives," and many other series, as well as in such acclaimed telefilms as 1997's Tuskegee Airmen drama "Miss Evers' Boys." More recent work, all of it up to Woodard’s usual high standards, includes a surprisingly dimensional characterization as a murderously corrupt politician on the Marvel/Netflix series “Luke Cage” (2016-2018) and a heavy role as a warden forced to consider death-penalty issues in “Clemency” (2019).

Woods, James. Mr. Intensity, b. 1947. While it may seem as if there’s no room for subtlety in Woods’ take-no-prisoners approach to acting, he grounds his best performances in small nuances. It just happens that once he gets going, those nuances blend seamlessly into an overpowering assault. Notorious for offscreen extremes—particularly his bizarro spat with movie siren Sean Young—Woods is reportedly a genius with the MENSA membership to prove it. He first caught notice playing crazies in “The Onion Field” (1981), “Fast-Walking” (1982), “Videodrome” (1983), and other pictures. This led to bigger movies, so he played devious crooks in “Against All Odds” and “Once Upon a Time in America” (both 1984). Then he scored a breakthrough (and an Oscar nomination) by playing Richard Boyle, the asshole photographer at the center of Oliver Stone’s harrowing drama “Salvador” (1986). Thereafter, Woods notched dozens of appearances in good movies, bad movies, and indifferent movies. At his best, he crafts incisive portraits of extreme characters, as in the 1992 telefilm “Citizen Cohn,” featuring Woods as notorious lawyer Roy Cohn. At his worst, he’s a wonderfully entertaining ham, as in the 1998 John Carpenter flop “Vampires,” in which Woods bags bloodsuckers like a supernatural big game hunter. Alas, Woods become a persona non grata in Hollywood during the 2010s, owing in no small part to his emergence as a odious blowhard within the extremes of the far-right political sphere.

“The World According to Garp” (1982). Hollywood’s uneven relationship with the novels of John Irving got off to a remarkable start with George Roy Hill’s outrageous dramedy. Neatly shaped into a movie story by master screenwriter Steve Tesich, the picture tracks the personal and artistic growth of one T.S. Garp (Robin Williams), a novelist who seems like the only sane witness to a world gone mad. His coterie of unusual intimates includes his mother, Jenny (Glenn Close), an unorthodox nurse; his transsexual friend, Roberta (John Lithgow), a former NFL player; and Garp’s wife, Helen (Mary Beth Hurt), whose infidelity leads to a grotesque accident. Featuring several whiplash tonal shifts, the picture balances bawdy comedy, bittersweet emotion, sharp social commentary, and transporting wonderment, often within the same scene. There’s even room for one of Irving’s great passions: wrestling. (Watch for the author’s cameo as a referee.) Many story elements veer into absurdity, but “Garp” is neither so weird that it lacks credibility nor so earnest that it lacks individuality. Playing one of the few characters expansive enough to contain all the aspects of his screen persona, Williams gives his first great dramatic performance, and every exceptional player in this strange movie matches him with equal levels of commitment and sincerity.

Wright, Jeffrey. Actor, b. 1965. Calling an actor "chameleonic" isn't especially imaginative, but no other adjective better captures Wright's ability to submerge himself in parts of every possible type. In "Basquiat" (1996), he's a downtown artist powered by hubris and inspiration; in "Shaft" (2000), he steals the show from no less a figure than Samuel L. Jackson as a terrifying killer; in "Syriana" (2005), he's a tormented litigator beset by corrupt businessmen and an alcoholic father; and in his signature piece, the stage and screen versions of Tony Kushner's epic play "Angels in America," he plays three wildly different characters. Wright can incarnate everything from semi-literate street thugs to uptight Ivy Leaguers, and he infuses all his roles with rich ambiguity. As soon as he comes onscreen, it's evident that Wright hasn't judged his characters, because he's too busy becoming them. Of late, Wright has been most visible in arty TV commercials and as part of the ensemble of the mind-bending HBO series "Westworld," which debuted in 2016.

"The Yakuza" (1975). More than being a confluence of top talent, "The Yakuza" is a deeply '70s thriller in that it gives equal screen time to adult emotion and visceral action. Starring Robert Mitchum at his laconic best as a WWII vet with deep connections to Japan, the film introduced the concept of Japanese organized crime to mainstream audiences more than a decade prior to Ridley Scott's "Black Rain." Japanese star Ken Takakura brings world-weary grace to his role as Mitchum's guide into the Asian underworld, a role he more or less reprised in "Black Rain." Directed with signature romanticism and "Three Days of the Condor" flair by Sydney Pollack, the piece was written by screenwriting god Paul Schrader and his brother Leonard (who had lived in Japan), then polished by another legendary scribe, Robert Towne. Also boasting industrial-strength character players Herb Edelman, Richard Jordan, Brian Keith, and James Shigeta, the downbeat story of an everyman drawn into a criminal plot with unexpected tethers to his past is tense, thoughtful, and touching.

"The Yards" (2000). Cowriter-director James Gray's downbeat drama is so steeped in '70s stylistic flourishes—dark photography influenced by Gordon Willis, deliberate pacing reminiscent of Sidney Lumet—that the presence of Me Decade stalwarts Ellen Burstyn, James Caan, and Faye Dunaway feels organic. Mark Wahlberg plays an ex-con whose desire to stay out of trouble is complicated by his friendship with ambitious hood Joaquin Phoenix, and Charlize Theron is the woman torn between them. The film's novelty and credibility come from its unusual milieu, New York City's subway train yards; the story uses the yards to get at the complicated interplay between organized labor, government, and organized crime. A thoughtful, adult study of conflicted morality somewhat along the lines of "Donnie Brasco" (1997), "The Yards" is a juicy throwback to the glory days of hard-hitting American dramatic films.

“Year of the Dog” (2007). Confidently helming his directorial debut, “Chuck & Buck” screenwriter Mike White delivers another plaintive ode to a misfit. “Saturday Night Live” alum Molly Shannon plays Peggy, a lonely, middle-aged office drone whose only real comfort comes from her beloved beagle, Pencil. So when Pencil dies, Peggy slips into a tailspin involving unlucky romantic entanglements, desperate attempts to find a new pet, and finally a life-changing immersion in the animal-rights community. Shot in simple, nonjudgmental tones and assembled with a novelist’s sense of whimsy and rhythm, the movie is a hundred things at once: heartbreaking, riotous, satirical, sentimental, political, engrossing. I’ll happily admit to being an easy mark for this one since I’m a dog person down to my Milkbones, but even beyond telling a story about the uncomplicated beauty of animals, White delivers an utterly unique tale about the very complicated beauty of humans, particularly those whom most of us dismiss as lost causes.

“Zelig” (1983). Armchair shrinks can have a field day with Woody Allen’s portrayal of Leonard Zelig, a man so insecure he physically transforms into copies of those around him; after all, Allen is the prototypical shy guy who hides behind humor and an affected persona. Zelig’s story is told in playful mockumentary style, with convincing effects that replicate vintage film stock and visual tricks that put Allen alongside historical figures. Yet even with the rich psychological implications and the impressive technical achievements, the movie never forgets to be funny in that unmistakable Allen way. Sample narration: “The Ku Klux Klan, who saw Zelig as a Jew that could turn himself into a Negro and an Indian, saw him as a triple threat.” Allen stalwart Mia Farrow is delicately sweet as the love interest, a doctor who tries to unravel Zelig’s jumbled psyche, and the movie zips along breathlessly during its 79-minute running time.

Zerbe, Anthony. Actor, b. 1936. With regal features suited for epic scowling and the ability to imbue dramatic pauses with true suspense, classically trained actor Zerbe has employed his offbeat magnetism to portray everything from messianic leaders to megalomaniacal loons. Given that Zerbe eventually settled into a groove playing sophisticated characters, it’s surprising that he first caught notice playing hot-tempered rubes. In pictures like “The Liberation of L.B. Jones” and “The Molly Maguires” (both 1970), Zerbe plays working-class men doomed to unfortunate fates because of their proclivity for violence. (That same year, he played a murderous pimp in the lurid Sidney Poitier thriller “They Call Me Mister Tibbs!”) It’s not just any actor who can claim on his resume roles as an imprisoned dog handler (in 1967’s “Cool Hand Luke”), the leader of a murderous postapocalyptic horde (in 1971’s “The Omega Man”), a noble leper (in 1973’s “Papillon”), a second-tier Bond villain (in 1989’s “License to Kill”), a Starfleet admiral (in 1998’s “Star Trek: Insurrection”), and a futuristic politician (in 2003’s “Matrix” sequels). Moreover, it’s not just any actor who can surmount the indignity of starring in one of the most infamous telefilms of the Me Decade—Zerbe played the mad scientist who tussles with a superpowered supergroup in 1978’s “Kiss Meets the Phantom of the Park.” As demonstrated by his appearances in countless films and TV episodes after his run-in with Messers. Criss, Frehley, Simmons, and Stanley, not even four New Yorkers in Kabuki makeup and platform shoes were enough to derail Zerbe’s enduring run as a top character player.

“Zodiac” (2007). A painstaking procedural about the hunt for a killer who stalked the California coast from the late '60s through much of the '70s, David Fincher's austere drama delivers a probing examination of how homicide affects many more people than the loved ones of victims. Methodically depicting parallel investigations mounted by a driven policeman (Mark Ruffalo) and a surprisingly deft newspaper cartoonist-turned-amateur sleuth (Jake Gyllenhaal), Fincher uses Robert Graysmith's best-selling nonfiction book as the foundation for a moody epic about souls drawn inexorably into the blackness of a killer's madness. Bucking the gory trends of the day, Fincher relegates the slasher bits to quick, effective vignettes that amplify how horrific Zodiac's grisly deeds were. Complementing suspenseful murder scenes are provocative conversations that range from thrilling moments in which investigators piece together disparate clues to gut-wrenching episodes in which the protagonists knowingly succumb to the siren call of solving a mystery. That they never achieve their goal underscores the chilling thematics of this ambitious movie. And as if the fastidious production design and pervasively ominous vibe weren’t enough, the picture features several exemplary performances, particularly Robert Downey Jr.’s turn as a doomed journalist whose spiral into a drugged haze is exacerbated by his preoccupation with the Zodiac case.

A-C D-F G-I J-L M-O P-R S-U V-Z

home • news • books and movies • field guide • services • journalism • gallery • bio