peter hanson's field guide to interesting film

Madsen, Virginia. Recovering vixen, b. 1961. Seductive and composed in even her earliest appearances, Chicago-bred beauty Madsen cut such a striking figure in a series of trivial '80s movies that typecasting as a femme fatale was inevitable. She somehow retained her dignity, if not her clothes, through years of thankless roles as slatterns and twits, essaying more memorable characters in "Long Gone," a 1987 telefilm similar in spirit to the following year's theatrical release "Bull Durham," and "The Hot Spot," Dennis Hopper's sweaty 1990 neo-noir. Both pictures displayed her wry comic skills as well as her head-turning looks. She spent much of the '90s vainly flexing her dramatic chops in rote women-in-jeopardy pics, of which the Yakuza-themed "Blue Tiger" (1994) is perhaps the most distinctive. (Her brother, Tarantino regular Michael Madsen, makes a cameo in the moody thriller.) Poised for a renaissance with a solid dramatic turn in the Francis Coppola-helmed John Grisham flick "The Rainmaker" (1997), Madsen finally earned her due respect thanks to "Sideways" (2004). Her work in the smart Alexander Payne dramedy garnered an Oscar nomination and reinvigorated her career. The momentum sputtered somewhat after Madsen landed in flops like “The Number 23” (2007) and the short-lived Ray Liotta series “Smith” (2006-2007), but Madsen took a more assertive role in her career in in 2009 by producing the documentary "I Know a Woman Like That" (which Madsen's mother, Elaine, directed). More recent work includes plentiful appearances across film and TV, such as a solid run as an opportunistic politician on the 2016-2017 debut season of “Designated Survivor.”

Mako. Actor, 1933-2006. For more than 40 years, diminutive powerhouse Mako gracefully bore the burden of representing an entire culture. Whether cast as a WWII general, a feudal lord, or a contemporary martial-arts master, Mako was inevitably hired to provide authentic Japanese atmosphere. His clenched facial expressions and rough voice were instantly familiar, and it's a measure of his malleability that he was able to segue from silly voice work on the cartoon "Duck Dodgers" to a meaningful role as a Nobel laureate on "The West Wing," as he did in 2005. A Japanese native, Mako scored an Oscar nomination for "The Sand Pebbles" in 1966, and he enjoyed a boom period of sorts during the '80s. In addition to appearing in a number of dismal martial-arts movies, including those starring frequent employer Chuck Norris, he gave an entertainingly batty performance as a magician in "Conan the Barbarian" (1982), which he also narrated. Mako's leading performances were few, with his turn in the sensitive 1988 indie "The Wash" of special note.

Malick, Terrence. Enigma, b. 1943. For two decades, from the late '70s to the late '90s, Malick enjoyed a curious status as the J.D. Salinger of movies, the genius who walked away from a career on the rise. After notching some credits as a screenwriter (notably the 1972 Paul Newman/Lee Marvin picture "Pocket Money"), Malick made his presence known with "Badlands" (1973), one of the most impressive directorial debuts in the history of American cinema, then defined himself with the beautiful but opaque "Days of Heaven" (1978). A great deal of the Malick mythos stems from reports that that most exterior scenes for "Days of Heaven" were filmed at magic hour, a directorial choice seen by some as heroic and by others as hubristic. His subsequent withdrawal from the industry gave rise to intriguing rumors—He's a recluse! He's shooting test footage in Europe! He gets a stipend from Warner Bros. even though he doesn't make movies!—that bolstered Malick's enigmatic allure. Therefore a letdown of sorts was inevitable when Malick finally reemerged with 1998's "The Thin Red Line," a beautiful but hazy tone poem about war that seemingly featured every reputable male actor on the face of the earth. "The New World" (2005) diminished Malick's legend a little bit more, because once again painterly visuals overcompensated for a fuzzy script. Since then, Malick has been on what for him can only be called a hot streak, though he continues to favor cinematic texture over narrative concerns. Still, there's no denying the beauty and spirituality of certain passages in, say, "The Tree of Life" (2011), a dense piece that challenges viewers to parse its meaning. Plus, it's not as if Malick has wholly divorced himself from classical storytelling. Consider the powerful emotions that course through the soft-spoken WWII piece "A Hidden Life" (2019), easily his best and most coherent picture since "The Thin Red Line." Although "A Hidden Life" suffers for its voluptuous running time, the picture is a gorgeous exhibition of Malick's magical approach to cinematography, editing, and scoring.

Malick, Terrence. Enigma, b. 1943. For two decades, from the late '70s to the late '90s, Malick enjoyed a curious status as the J.D. Salinger of movies, the genius who walked away from a career on the rise. After notching some credits as a screenwriter (notably the 1972 Paul Newman/Lee Marvin picture "Pocket Money"), Malick made his presence known with "Badlands" (1973), one of the most impressive directorial debuts in the history of American cinema, then defined himself with the beautiful but opaque "Days of Heaven" (1978). A great deal of the Malick mythos stems from reports that that most exterior scenes for "Days of Heaven" were filmed at magic hour, a directorial choice seen by some as heroic and by others as hubristic. His subsequent withdrawal from the industry gave rise to intriguing rumors—He's a recluse! He's shooting test footage in Europe! He gets a stipend from Warner Bros. even though he doesn't make movies!—that bolstered Malick's enigmatic allure. Therefore a letdown of sorts was inevitable when Malick finally reemerged with 1998's "The Thin Red Line," a beautiful but hazy tone poem about war that seemingly featured every reputable male actor on the face of the earth. "The New World" (2005) diminished Malick's legend a little bit more, because once again painterly visuals overcompensated for a fuzzy script. Since then, Malick has been on what for him can only be called a hot streak, though he continues to favor cinematic texture over narrative concerns. Still, there's no denying the beauty and spirituality of certain passages in, say, "The Tree of Life" (2011), a dense piece that challenges viewers to parse its meaning. Plus, it's not as if Malick has wholly divorced himself from classical storytelling. Consider the powerful emotions that course through the soft-spoken WWII piece "A Hidden Life" (2019), easily his best and most coherent picture since "The Thin Red Line." Although "A Hidden Life" suffers for its voluptuous running time, the picture is a gorgeous exhibition of Malick's magical approach to cinematography, editing, and scoring.

Malle, Louis. Writer-director, 1932-1995. That it's difficult to reconcile how the man who made "Lacombe Lucien" (1974), a sober drama about WWII French collaborators, also made "Crackers" (1984), a directionless crime farce, illustrates the chameleonic nature of Malle's artistry. Born to privilege, he seemed driven by an expansive intellectual curiosity from the beginning of his career; his first feature credit is an undersea documentary codirected by legendary explorer Jacques Cousteau. Malle's early French films offer a buffet of genres, his '50s and '60s work melding sometimes controversial subject matter with stylistic classicism. He returned to documentaries for a little-seen 1969 TV series called "Phantom India," then embarked on a productive '70s streak that boasted his first two masterpieces and his first two Hollywood movies. Arguably his most important film of the period was 1971's "Murmur of the Heart," his sensitive nostalgia piece about a young boy having sex with his mother; the story should feel distasteful, but it somehow plays organically and with great charm, adding to the suspicion that the tale was autobiographical. Of Malle's American movies, the most interesting are "Atlantic City" (1981), a beautifully wrought character piece about colorful losers in the mode of John Huston's downbeat '70s films, and "My Dinner With Andre" (also 1981), the notorious talkathon that's neither as entertaining as its champions claim nor as dull as its detractors insist. Malle's output slowed down in the '80s and early '90s, during which he made some of his most deftly crafted stories, especially 1987's "Au revoir les enfants." A ruthlessly concise remembrance of the tragedy that took Malle's innocence, the movie is distinguished by austere visuals, a meditative tone, and truly perfect casting.

"Manhunter" (1986). Everything about this stylized crime movie is so vivid and memorable that its status as the first Hannibal Lecter flick is not its most important attribute. Helmed confidently by Michael Mann, "Manhunter" tracks the attempts of anguished FBI investigator Will Graham (William L. Petersen) to identify and stop a serial killer perversely known as "The Tooth Fairy." Little problem—Graham's still reeling from his run-in with Lecter (Brian Cox), who's now imprisoned and, unfortunately for Graham, a key source of information and guidance. The tense ballet that ensues between Graham and the his quarry, serial killer Francis Dollarhyde (Tom Noonan), reveals the demons in each of their souls while also sparking paroxysms of horrific violence. In the full throes of his "Miami Vice" period, Mann loads the movie with garish '80s style, balancing inevitable extremes with softer nuances, such as an eerily sensual visit to a zoo. He also fills the screen with remarkable acting. Petersen is achingly soulful, Noonan is otherworldly and touching, and Cox seems like the devil incarnate. Joan Allen, Dennis Farina, Kim Greist, and Steven Lang add textures that are just as important to Mann's rich, disturbing canvas.

Mann, Michael. Writer-director, b. 1943. Whether he's working in TV or features, I find Mann's best work endlessly rewarding, and nobody has made more movies that I revisit more often. "Thief" (1981), his first theatrical feature, possess a hypnotic quality and an open heart I find comforting, while its sister film, "Heat" (1995), dazzles with virtuoso action scenes and a sprawling cast of actors whose work I adore. "The Last of the Mohicans" (1992) is such a sweeping historical romance that it makes me forget I don't like sweeping historical romances, and I can just about quote whole scenes from Mann's Hannibal Lecter movie, "Manhunter" (1986). That I haven't even gotten to the whip-smart "The Insider" (1999) and the passionate "Ali" (2001) says a great deal about the depth of Mann's output. I suppose it would be disingenuous to avoid mentioning that this extraordinary writer-director first caught my eye with a project he neither wrote (at least not for credit) nor directed—the groundbreaking '80s TV series "Miami Vice," for which he served as executive producer. His association with the show started many critics down the road of lamenting that Mann often presents more style than substance, but the detail layered into every character and scene in his movies reveals that, when he's operating at the height of his powers, both ends of the style/substance spectrum are of equal importance to him. Even in projects that strike me as missteps, Mann inevitably renders at least one distinctive characterization or one spellbinding sequence, if not both. He also possesses nearly infallible taste in actors. Mann was the first guy to put Dennis Farina and William L. Petersen onscreen (both played small parts in "Thief"), and he has again and again shown great aptitude for creating ensembles.

Mann, Michael. Writer-director, b. 1943. Whether he's working in TV or features, I find Mann's best work endlessly rewarding, and nobody has made more movies that I revisit more often. "Thief" (1981), his first theatrical feature, possess a hypnotic quality and an open heart I find comforting, while its sister film, "Heat" (1995), dazzles with virtuoso action scenes and a sprawling cast of actors whose work I adore. "The Last of the Mohicans" (1992) is such a sweeping historical romance that it makes me forget I don't like sweeping historical romances, and I can just about quote whole scenes from Mann's Hannibal Lecter movie, "Manhunter" (1986). That I haven't even gotten to the whip-smart "The Insider" (1999) and the passionate "Ali" (2001) says a great deal about the depth of Mann's output. I suppose it would be disingenuous to avoid mentioning that this extraordinary writer-director first caught my eye with a project he neither wrote (at least not for credit) nor directed—the groundbreaking '80s TV series "Miami Vice," for which he served as executive producer. His association with the show started many critics down the road of lamenting that Mann often presents more style than substance, but the detail layered into every character and scene in his movies reveals that, when he's operating at the height of his powers, both ends of the style/substance spectrum are of equal importance to him. Even in projects that strike me as missteps, Mann inevitably renders at least one distinctive characterization or one spellbinding sequence, if not both. He also possesses nearly infallible taste in actors. Mann was the first guy to put Dennis Farina and William L. Petersen onscreen (both played small parts in "Thief"), and he has again and again shown great aptitude for creating ensembles.

"The Man Who Would Be King" (1975). In some ways a companion piece to his '50s triumph "The Treasure of the Sierra Madre," this is John Huston's other great adventure about the power of gold. Adapted gracefully from Rudyard Kipling's story, the unabashedly old-fashioned tale follows scurrilous Brits Daniel (Sean Connery) and Peachy (Michael Caine) as they venture from 19th-century India to remote Kafiristan with the goal of plundering "savage" lands for wealth. The morality tale is deceptively simple, with one partner staying focused while the other succumbs to delusions of grandeur, and Huston uses this solid narrative architecture to support both boisterously entertaining action scenes and delightful passages of playful interaction. Connery and Caine are so terrific together it's a shame they never reteamed, but the upside is they never tainted the memory of this utterly absorbing film. Employing his considerable linguistic powers as well as his gift for capturing the atmosphere of exotic places, Huston is in bravura form all the way through, even if the wraparound bits with Christopher Plummer (as Kipling) are a bit corny. "Maria Full of Grace" (2004). Whereas Steven Soderbergh's "Traffic" (2000) took an expansive view of the drug trade, Joshua Marston's disturbing film examines the issue from an intimate perspective. With methodical tenacity, writer-director Marston tracks the journey of Maria (Catalina Sandino Moreno), a young Colombian who grows to see an illicit drug run as the only means of escaping her financially precarious situation. Instead of presenting her as a naïf manipulated by bad men, Marston smartly portrays Maria as a level-headed pragmatist who thinks she can control a process that she knows has chewed up and spit out dozens, if not hundreds, of women just like her. Though the film's iconic scene is the stomach-turning sequence in which Maria ingests baggies filled with cocaine, every stretch of Marston's picture is filled with vivid realism. Viewers get a strong sense of the title character's vibrant life in Colombia, cringe with the blind terror of her trek to the United States, and reel with the twists that complicate her lot once she arrives in New York. Martin, Strother. Actor, 1919-1980. Considering that he actually hailed from Indianapolis and that he spent his early professional life as a swimming instructor, it’s peculiar that Martin found his niche playing characters that he playfully categorized as “prairie scum.” But if ever the movies benefited from a case of typecasting, then Martin’s was that case. Over the course of nearly 150 TV and film appearances, particularly those from the mid-’60s to the time of his death in 1980, Martin used his small frame, fidgety body language, and snake-oil-salesman vocal style to personify villains, vagabonds, and varmints. Though he was already gainfully employed as an actor by the mid-’60s, owing in part to bonding with TV and feature helmer Sam Peckinpah, Martin won a measure of cinematic immortality by playing the despicable captain of a prison road gang in “Cool Hand Luke” (1967). His flamboyant delivery of the line “What we got here is a failure to communicate” immediately became a beloved piece of movie history. Though few subsequent roles were as iconic, Martin made invaluable contributions to a handful of terrific films even though most of his filmography comprises routine entertainments and a lot of cinematic garbage. He’s at his wonderful worst in pictures like “The Ballad of Cable Hogue” (1970) and “Hannie Caulder” (1971), both of which feature Martin as Old West trash of the most lascivious type. Yet he was probably most entertaining when he blended his over-the-top villainy with comedic elements, as in “Pocket Money” (1972) and “Slap Shot” (1977). In both pictures, he plays manipulative authority figures who eventually get exposed as pathetic losers striving vainly for undeserved success. Though most frequently asked to personify irredeemable slime, Martin truly shined as a sympathetic interpreter of floundering bottom-dwellers. "The Matador" (2005). Highly entertaining silliness about a hit man losing his edge, Richard Shepard's breezy comedy-thriller may well be the best thing Pierce Brosnan has done, blending the swagger of his Bond/Remington Steele persona with a winning fragility he rarely displays. The plot, a canard in which Brosnan's killer gets ensnared with Greg Kinnear's traveling businessman, is a contrivance allowing for the culture clash between Eurosleaze and plastic America. Loaded with off-color bon mots and likeably dopey physical humor, the picture also features as its concealed weapon indie iron woman Hope Davis. Laced with just enough character dimension to justify its running time, the picture's far from effortless, but it goes down as smoothly as those martinis Brosnan used to swig in between dispatching henchmen for queen and country. Matheson, Richard. Fantasist, 1926-2013. A prolific novelist, screenwriter, and short-story writer whose body of work includes some of the most influential fantasy stories of the modern era, Matheson is a giant whose name belongs in the same pantheon as those of Ray Bradbury, Harlan Ellison, and Stephen King. Among his longest-lasting works are the existential sci-fi movie “The Incredible Shrinking Man” (1957), the script for which Matheson adapted from his novel “The Shrinking Man”; the postapocalyptic vampire novel “I Am Legend,” which has inspired a number of official and unofficial adaptations, including the 2007 Will Smith thriller bearing the original title and cult-fave versions starring Vincent Price (1964’s “The Last Man on Earth”) and Charlton Heston (1971’s “The Omega Man”); the 1980 movie “Somewhere in Time,” a schmaltzy romance with Christopher Reeve and Jane Seymour that Matheson adapted from his novel “Bid Time Return”; and numerous short scripts for television, including the classic “Twilight Zone” segment “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” (1963), about a passenger who sees a gremlin on the wing of a plane, which was remade 20 years later for “Twilight Zone: The Movie.” Matheson’s monumental output also includes a string of evocative TV movies, notably “Duel” (1971), the man-vs.-truck thriller that helped director Steven Spielberg graduate from TV to features, and “Prey,” Matheson’s contribution to the creepy 1975 anthology telefilm “Trilogy of Terror”; that’s the cult-fave vignette with Karen Black getting stalked by a voodoo doll. Simply listing Matheson’s career highlights would be exhausting, because from the mid-’50s to the late ’80s, Matheson was one of Hollywood’s most reliable storytellers in the horror/fantasy realm, whether he was adapting existing material, crafting original work for the screen, or simply providing source material through his many novels and short stories. Not everything Matheson touched turned to gold—some of his ’70s telefilms are fluffy potboilers, and a few of his features, like the lurid 1969 biopic “De Sade,” are notorious disasters—but Matheson’s career is nonetheless a monument to imagination. McDonnell, Mary. Actor, b. 1952. Go figure that an acclaimed New York stage actor with two Oscar nominations under her belt would find one of her richest roles in a sci-fi action show. But week after week on the daring revamp of "Battlestar Galactica" (2003-2009), McDonnell added emotional grace notes as a schoolteacher-turned-politician battling everything from military coups to killer robots. As for those two well-deserved Oscar noms, they both came in her early-'90s breakthrough period, which followed years of celebrated stage work and smallish TV and movie roles. She scored a Supporting Actress nod for "Dances With Wolves" (1990), in which she added fresh energy and gigantic hair to the familiar role of a white woman won over by Indian ways, and a Best Actress nod for "Passion Fish" (1992), in which her grit and humor fit the layered character of a wheelchair-bound diva. McDonnell also enjoys an odd distinction for those who savor Hollywood trivia—like George Clooney, she's a veteran of both the '80s sitcom "E/R," on which she was a regular, and the enduring drama "ER," on which she played an embittered blueblood for several episodes in 2001 and 2002. McMillan, Kenneth. Actor, 1932-1989. With his short and rotund physique, to say nothing of his perpetually flushed cheeks, McMillan was sure to get typecast as exasperated antagonists once he entered films at the tender age of 41. But because he complemented his physicality with a glorious ability to shift between portrayals of likeable losers and personifications of vile monsters, McMillan ensured that his ten-year hot streak was filled with variety. Beginning with his first standout performance, as a cowardly sheriff in the 1979 Stephen King telefilm “Salem’s Lot,” McMillan carved a unique niche by coloring dialogue with unexpected, nervous inflections, making each new line more surprisingly lilting and affecting than the previous. He’s as winning as a flustered baseball manager in “Blue Skies Again” (1983) as he is grotesque as an outer-space aristocrat in “Dune” (1984). Similarly, his performance as a doomed safecracker in “The Pope of Greenwich Village” (1984) is as touching as his portrayal of an appallingly racist cop in “Ragtime” (1981) is repulsive. “Meek’s Cutoff” (2010). Spare and haunting, director Kelly Reichardt’s grim drama depicts the misadventures of Old West homesteaders who imprudently break off from a wagon train. Offering a feminist spin on American history, the picture focuses on Emily Tehterow (Michelle Williams), the strongest woman in the group, as she tries to keep hysteria and paranoia from doing even more damage to her group than exhaustion and thirst. Emily’s efforts are stymied by the group’s jackass guide, Stephen Meek (Bruce Greenwood), a self-proclaimed expert tracker whom the homesteaders quickly realize is a grandstanding liar. Emily has a close ally in her sensitive husband, Soloman (Will Patton), but because neither are prepared for weeks in the barren wilderness of unsettled Oregon, their respectful teamwork may not be enough to guarantee survival. Reichardt methodically illustrates the way the group fractures when hardships accrue, and she’s at her best showing the group’s conflict about how to handle an Indian prisoner (Rod Rondeaux). A thoughtful alternative to the usual action tropes of the Western genre, “Meek’s Cutoff” is a sobering demonstration of how much insane risk was involved in trying to conquer the American frontier. Meyer, Nicholas. Writer-director, b. 1945. How's this for irony—though best known for his stories set in the future, Nick Meyer is among the American filmmakers most deeply rooted in the past. An erudite, funny writer who worked on a few junky pictures before scoring with his novel and screenplay "The Seven Per-Cent Solution" (1976), an outlandish lark about Sigmund Freud becoming Sherlock Holmes' analyst, he trod similar terrain in his directorial debut, "Time After Time" (1979), which pits H.G. Wells against Jack the Ripper. Both projects radiate Meyer's affection for times before his own. And then, in a head-spinning switch he probably never expected, Meyer found himself directing the best big-screen outing of the U.S.S. Enterprise, 1982's "Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan." With an uncredited rewrite that condensed the best ideas from several disparate drafts and then injected a few thoughts of his own, Meyer gave the "Trek" franchise the grandeur, high adventure, and literary allusions that distinguished the best episodes of the original series, tossing in a submarine-style showdown for good measure. As he ventured on to other projects, Meyer maintained an on-and-off relationship with "Trek" through to the big-screen signoff of the franchise's original cast. Among those "other projects" was a little thing called "The Day After" (1983), a harrowing drama about a fictional nuclear holocaust that remains the most-watched telefilm in history. Of late, Meyer has set aside directing to concentrate on writing, penning well-received historical fiction, including more Sherlock Holmes adventures, and authoring smart scripts for pictures including "The Human Stain" (2003). “Michael Clayton” (2007). A perfectly timed thriller for the era of legally sanctioned corporate malfeasance, screenwriter Tony Gilroy’s impressive directorial debut employs a spectacular cast to tell the story of a law-firm “fixer” whose various personal crises put him in a position to expose the high-stakes wrongdoing of his corporate clients. George Clooney, complicating his movie-star persona with a textured portrayal, stars as Clayton, a man coming to grips with the moral ramifications of helping the rich get away with heinous crimes, and he’s surrounded by world-class supporting actors: Tom Wilkinson is amazing as a law-firm eccentric whose personal spiral triggers Clayton’s introspection; Tilda Swinton won an Oscar for her multifaceted performance as a corporate operator trying to cover up a cover-up; and the late, great film director Sydney Pollack gives one his best acting performances as Clayton’s insidiously pragmatic mentor. Clever, exciting, frightening, and surpassingly intelligent, “Michael Clayton” is the kind of smart suspense Hollywood rarely makes anymore. “Midnight Run” (1988). For my tastes, “Midnight Run” is the epitome of the action-comedy genre that dominated multiplexes during the ’80s. The Martin Brest-directed charmer stars Robert De Niro, in one of his first comedic roles, as Jack Walsh, a bargain-basement bounty hunter chasing former mob accountant Jonathan Mardukas (Charles Grodin), who embezzled money from gangsters before going into hiding. Walsh wants the hefty fee he’ll get for surrendering Mardukas to authorities, and Mardukas wants to stay hidden because he’s on a hit list. Once Walsh corrals Mardukas, a farce ensues as the two make their way from New York to LA while being trailed by a competing bounty hunter (John Ashton), a persistent FBI agent (Yaphet Kotto), and bumbling assassins in the employ of short-tempered goodfella Jimmy Serrano (Dennis Farina). Plot devices that felt contrived in dozens of similar movies feel fresh in “Midnight Run,” because screenwriter George Gallo invests every character with relatable traits. Brest also achieves the difficult balancing act of meshing jokes with violence, so the picture feels like it has real danger even as elaborate physical comedy unfolds. Best of all, the performances are uniformly great. Farina is particularly funny delivering this weirdly specific threat: “You better start getting more personally involved in your work,” he bitches at one point to an underling, “or I’m gonna stab you through the heart with a pencil.” Milius, John. Militarist, b. 1944. "Conan, what is best in life?" "To crush your enemies, to see them driven before you, and to hear the lamentation of their women!" If ever a director used a character to articulate his philosophy of life, then surely Milius let Arnold Schwarzenegger's lunkheaded berserker in "Conan the Barbarian" (1982) speak for the wildest part of his soul. An outsized personality with John Huston's machismo but lacking Huston's sensitive side, Milius is a deeply beloved figure among many devotees of the New Hollywood era, particularly because of how his extreme right-wing perspective contrasts with the peace-and-love attitudes of his '70s peers. In movie after movie, whether as writer or director or both, Milius celebrates a Neanderthal worldview centered around heavily armed studs, pliant women, black-and-white morality, and the honor found in pursuing a noble goal, be it devotion to one's country (as long as it's America) or the pursuit of a truly bitchin' wave. All of this would of course be repulsive if not for Milius' luxuriant writing style, which more often than not features characters delivering spellbinding monologues that delineate their identities in grandiose terms. On a good day, Milius writes something eccentric and powerful like "Jeremiah Johnson" (1972) or "Apocalypse Now" (1979); on a bad day, he spews fascistic drivel like "Red Dawn" (1984). But this notorious gun nut is a key figure in modern movies, because no matter what else, he's widely believed to be the man behind Dirty Harry's best lines (think "Do you feel lucky, punk?") and Robert Shaw's mesmerizing "U.S.S. Indianapolis" monologue in "Jaws" (1975). Whether true or not, those myths suit the persona of an iconoclast who has made his living chronicling larger-than-life adventures. Although still recovering from a severe stroke that temporarily robbed him of the power to speak, Milius bravely participated in a celebratory documentary about his career, aptly titled "Milius" (2013). Molina, Alfred. Actor, b. 1953. A burly, dark-haired Englishman of Italian-Spanish descent, Molina kicked around world cinema for a more than a decade before he started landing roles commensurate with his alternately boisterous and poetic persona. His screen debut was in no less a picture than 1981’s “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” featuring Molina as the ill-fated cohort who double-crosses Indy during the opening sequence. At the height of his breakthrough period in the mid-’90s, he gave one show-stopping performance after another. He incarnated a blustery Cuban in “The Perez Family” and the unlucky lover of a homicidal alien in “Species” (both 1995), then played a coked-out crook in “Boogie Nights” (1997), complete with a nervy ensemble of tiny briefs and a bathrobe. Next came his Broadway debut in Yasmina Rena’s celebrated drama “Art”; a motor-mouthed monologue in the middle of the play helped nab Molina his first Tony nomination. Possibly his strongest role to date was in 2002’s “Frida,” the arty biopic costarring Molina as passionately political painter Diego Rivera; he easily stole the picture from well-intentioned leading lady Salma Hayek. Then came a characteristically varied one-two punch. In 2004, Molina went the blockbuster route playing tortured baddie Doctor Octopus in “Spider-Man 2,” then reaffirmed his artistic bona fides with a Broadway revival of “Fiddler on the Roof,” which netted him another Tony nod. (A third nomination came in 2010 for starring in John Logan’s “Red.”) Further acclaim, deservedly so, resulted from Molina’s angsty performance as real-life director Robert Aldrich in the campy TV miniseries “Feud: Bette and Joan” (2018); watching Molina scheme and squirm while enduring a diva duel is simultaneously cringe-inducing and delightful. Morse, David. Actor, b. 1953. Playing a character whose towering form gets hobbled by injury, Morse made a strong impression in his first major role, as a sidelined athlete in "Inside Moves" (1980). Right out of the gate, he exuded a combination of tenderness and toughness that made him a uniquely interesting screen presence. Morse made another strong impression as a long-suffering doctor on the TV drama "St. Elsewhere" (1982-1988), particularly during a bold-for-its-time storyline involving the trauma Morse's character experiences after being raped. Years of journeyman work in films and TV projects of varying quality followed the end of his steady gig on the acclaimed series. A notable highlight of these wilderness years was an affecting performance in "The Indian Runner" (1991) as a cop trying to keep his unstable brother from spiraling out of control. In the late '90s, Morse finally started scoring high-profile roles worthy of his talents, playing an inspiring dad in "Contact" (1997), a thuggish guard in "The Green Mile" (1999), and a resourceful kidnap victim in "Proof of Life" (2000). A rare leading role came his way when Morse toplined the short-lived action series "Hack" (2002-2004), and he received above-the-title billing for his nuanced performance as a corrupt policeman in the exciting thriller "16 Blocks" (2006). Notable work since then includes an Emmy-nominated turn as George Washington in the HBO miniseries “John Adams” (2008), plus series-regular roles in “Treme” (2010-2013) and “Outsiders” (2016-2017). "Mr. Holland's Opus" (1996). I have an almost inexplicable soft spot for this manipulative melodrama about a composer who inadvertently sidelines his ambitions to become a sensitive music teacher, my affection for the film primarily attributable to Richard Dreyfuss' commanding performance in the lead role. Giving an Oscar-nominated comeback turn after several years of phoned-in performances, Dreyfuss devours every onscreen moment, conveying arrogance, bitterness, regret, contrition, paternal love, and pride so acutely that it feels like Dreyfuss spent the production rediscovering the joy he derives from his craft. Even when saddled with mawkish scenes and iffy makeup—more the applications meant to make him appear younger than those utilized to age him—he hits every note with the precision of, appropriately enough, a world-class musician. "Mrs. Brown" (1997). When Queen Victoria's husband died, she went into two years of mourning until brash attendant John Brown abandoned decorum by telling the queen she was wasting her life. Brown's companionship rekindled the queen's joie de vivre, but rumors that she was romancing a commoner sparked controversy throughout 19th-century England. Soft-spoken, warm, and somewhat enigmatic, John Madden's movie of this intriguing historical chapter contains outstanding performances by both leading actors. As Victoria, Judi Dench dramatizes the stubbornness with which royals guard their emotions, and as Brown, Billy Connolly channels the mad energy of his stand-up comedy into an effective portrayal of a wild man who is, in his way, as repressed as the queen. Differing from most movies about monarchs because so many scenes take place outside the royal court, "Mrs. Brown" also provides a rare cinematic glimpse at a complicated relationship between middle-aged characters. “The Muppet Movie” (1979). The big-screen debut of Jim Henson’s felt-puppet musical-comedy troubadours stands alongside “The Wizard of Oz” (1939) as the only kiddie movie that affected me in my youth and still transports me today. A sweet story about Kermit the Frog’s noble dream of becoming an entertainer whose work makes people happy, “The Muppet Movie” unfolds as a road picture in which Kermit gathers his fellow muppets while traveling from his swamp on the East Coast to a wholly different swamp: Hollywood. The movie is peppered with big-name comedy cameos (Mel Brooks, Bob Hope, Richard Pryor, Steve Martin, and many more), all of which are great fun, and it features an imaginative subplot about a fast-food titan (Charles During) who wants Kermit to shill for a chain selling frog’s legs. Horrors! More importantly, the picture radiates hopefulness, a theme encapsulated in the key song by composers Paul Williams and Kenny Ascher, “The Rainbow Connection.” Frenzied and silly but at the same time deeply sincere, “The Muppet Movie” is, of all things, a celebration of simple idealism in the classic Frank Capra tradition. "My Favorite Year" (1982). "I'm not an actor, I'm a movie star!" Meet Alan Swann (Peter O'Toole), a flamboyant cinema swashbuckler who gets the shock of his life when he's told his appearance on a TV comedy will be broadcast live. The collision of British sophisticate Swann with the hyperkinetic, hyper-Jewish world of '50s television is the springboard for a delightful adventure in Richard Benjamin's warmhearted comedy. Mark Linn-Baker plays the TV flunky charged with shepherding Swann through a whirlwind week in New York, his job complicated by Swann's boozing and by a mobster bent on derailing the TV show, among other things. Though O'Toole is spectacular, flouncing and deteriorating in grandiose fashion, every member of the cast is spot-on. Joe Bologna plays a swaggering Sid Caesar type on the mock "Your Show of Shows," with quintessential New Yorkers Selma Diamond, Lainie Kazan, Bill Macy, and others adding rich Borscht Belt flavor. "My Summer of Love" (2004). Strong-willed but unsophisticated Mona (Nathalie Press) resents her seemingly pointless existence in the British countryside, where she's used by a crass adulterer and pitied by her born-again Christian brother. Then she meets Tamsin (Emily Blunt), a moneyed beauty who seems just as disenchanted with her own existence. Friendship comes quickly, and attraction takes both of them by surprise. The relationship predictably irks Mona's pious brother, so the lovers withdraw into a private world of intimacy and possibility. Press conveys an intense quality of bewildered need, and Blunt invests Tamsin with a beguiling combination of youthful arrogance and playful mystery. Watching these two delicately etched characters collide is compelling, even if director-cowriter Pawel Pawlikowski's style doesn't have much tonal variety. His eye is unerring, however, surrounding Mona and Tamsin with evocative textures and subtly unnerving camera motion. The storyline staggers a bit with the brother's third-act turnabout, but the payoff of the main narrative is dryly clever. Brisk, intuitive, and tastefully sensual, "My Summer of Love" is like Mona: deceptively simple and unexpectedly potent. “Near Dark” (1987). Quite likely the artiest movie ever made about redneck vampires, Kathryn Bigelow’s solo directorial debut is pure grisly delight. When a small-town youth (Adrian Pasdar) meets a seductive blonde (Jenny Wright), he’s inadvertently drawn into a gang of bloodsuckers who tour the West in search of plasma and thrills. Leading the gang is Jesse (Lance Henriksen), who memorably reveals that he’s been at this for quite a while, and right by his side is Severen (Bill Paxton), a wild man who relishes his wet work. The taut script, by Bigelow and Eric Red, puts a wry spin on monster mythology while setting up a handful of dazzling sequences—watch Paxton’s glee as he and his compatriots make short work of shit-kicker bar and its unlucky inhabitants. Featuring crisp long-lens photography and one of Tangerine Dream’s most atmospheric scores, the picture has more style than substance, but everyone involved seems utterly committed to the endeavor. “Never Cry Wolf” (1983). Carroll Ballard’s adaptation of naturalist Farley Mowat’s autobiographical book about researching Canadian wolves is a small cinematic miracle. Abetted by cinematographer Niro Marita and a willing cast, particularly leading man Charles Martin Smith, Ballard ventured deep into the tundra and patiently waited for nature to come alive before his cameras. Ballard’s vistas of the Canadian wilderness make the place seem magical and terrifying at the same time, and the “performances” his team coaxed from various wolves created the illusion that the picture was strung together from documentary footage. The story is mesmerizing, beginning when Tyler (Smith) is dumped into the wild with only a stack of supplies and a bundle of ignorant fears about wolves being man-eating monsters. Through observation and careful interaction, he grows to respect wolves as noble creatures that avoid man, making the film a kind of love story between Tyler and a magnificent species. When fate horrifically intrudes, the heartbreaking turn of events underscores not only the gulf between “civilized” man and the natural world, but also the inspiring resilience of the wolves. Smith gives a titanic performance, even contributing to the writing of the film’s evocative narration, and Mark Isham’s electronic score perfectly accentuates the forbidding grandeur of the locales. New Hollywood. Umbrella term for what journalist Peter Biskind named the "Easy Riders, Raging Bulls" period in his tasty tome of the same name. Roughly extending from 1969 to 1979, this was the halcyon span when young directors, many with counterculture sensibilities, made idiosyncratic films because studios were unmoored by the dissipation of the studio system, and had not yet identified the youth audience as their raison d'etre. Occurring coincidentally with my weaning, the New Hollywood era produced a greater number of American films I find interesting than any previous or subsequent period, as well as a style of squalid realism that grungy dramas of many successive eras have strained to emulate, with varying degrees of success. If it's a sedately paced mood piece starring Al Pacino or a similarly mannered surrogate as a hirsute lowlife trying to score horse in between rambling speeches about "the man," it's a New Hollywood movie or at least wants to be. “Nick & Norah’s Infinite Playlist” (2008). Every so often a movie that could have been utterly generic becomes something memorable simply because of ephemeral qualities that can’t be manufactured. Case in point: This lovely teen romance about a mopey musician and a drunk’s wing-woman. The slight plot, hinged on the quest for a secret show by a rock band as well as the concurrent search for a lost friend, is a tool for stringing together colorful incidents, so the charm is in the details. As the musician, Michael Cera offers his customary mixture of girly sensitivity and menschy integrity, and as the sidekick, Kat Dennings is disarmingly self-conscious (if you can accept the casting of va-va-voom Dennings as an ugly duckling). Director Peter Sollett and his team weave the story in dreamlike fashion, presenting New York tableaux that make the city seem like a musical wonderland filled with passionate rock fans casting about for soul mates. Songs by assorted indie bands (some performed onscreen and some layered onto the soundtrack) enrich the mood and amplify themes about a period in life when songs seem like the perfect vehicles for expressing emotion. Nighy, Bill. Actor, b. 1949. Tall and gaunt, with sunken eyes and impossibly high cheekbones, British actor Nighy passes quite easily for a ghoul when playing grotesque roles such as that of a vampire lord in "Underworld" (2003) and "Underworld: Evolution" (2006). Yet he's also just about the funniest son of a bitch on the planet, so he adds unexpected humorous flourishes to his baddie roles and absolutely kills when cast in out-and-out comedies. He was especially well-cast as dottering rock stars in "Still Crazy" (1998) and "Love Actually" (2003); in the latter, his zombified reading of a cheesy Christmas song is both a running joke and a comic highlight. Most impressively of all, Nighy is just as good when playing down-to-earth roles. As a lonely diplomat in "The Girl in the Café" (2005), Nighy certainly gets to play a fair share of comic bits, but what really connects is the deep ache he places inside his tragically repressed character. Though Nighy has acted since the mid-'70s, it wasn't until the late '90s that his breakout work in a handful of British films earned Hollywood's attention. Since then, his international profile has risen so steadily that he won the soggy role of Davy Jones in the "Pirates of the Caribbean" sequels. "The Ninth Configuration" aka "Twinkle, Twinkle Killer Kane" (1979). Eerie and offbeat, the directorial debut of William Peter Blatty, the novelist and screenwriter of "The Exorcist," concerns a secret facility where shell-shocked Vietnam vets are treated and screened for fakery. When a new shrink (Stacy Keach) is thrown into the mix at the improbable location of a gothic castle in fog-shrouded woods, things get dicey because Doctor Kane may well be loopier than any of his charges. Drawing on his background in light comedy, Blatty weaves absurd humor into the harrowing and frequently surreal picture, which feels a bit like a David Lynch version of "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest." The exemplary cast features Ed Flanders, Jason Miller, Joe Spinell, Scott Wilson, and others, each of whom contributes something human and strange to the singular goings-on. Weird, moving, and creepy, "Configuration" set the tone for Blatty's only other directorial endeavor, the underappreciated "The Exorcist III" (1990). Nolte, Nick. Method man, b. 1941. Time and again, Nolte has achieved notoriety for things that have nothing to do with his prodigious talent, from his hunkiness in the '70s to his DUI arrest (and corresponding mug shot) in 2002. After theatrical training at the Pasadena Playhouse, the Nebraska native eased into movies and TV with a number of forgettable appearances before scoring in the miniseries "Rich Man, Poor Man" (1976). Quickly pigeonholed because of his brooding good looks and muscular frame, Nolte lived up to low expectations by playing a beefcake hero in the lurid thriller "The Deep" (1977). Then he undercut preconceptions with serious-minded fare, such as 1978's "Who'll Stop the Rain," a drama about haunted vets, and 1979's "North Dallas Forty," a dramedy about debauched football stars. Nolte was reportedly considered for a number of big genre roles during his commercial heyday, including Han Solo, Indiana Jones, and Superman, but he didn't topline another popcorn flick until 1982's "48 HRS." By that point, he was fairly well established as an intense performer more interested in characters and stories than box-office returns. Moreover, Nolte’s memorable turn as a spiritual hobo in 1986's "Down and Out in Beverly Hills" marked the beginning of a slow transition from conventional leading-man gigs to more challenging roles. (Note that he takes second billing in such latter-day hits as "Cape Fear" and "The Prince of Tides," both released in 1991.) More important than his career arc, though, is his impressive artistic evolution. Among Nolte's exemplary credits are "Life Lessons" (Martin Scorsese's contribution to the 1989 anthology "New York Stories"), with Nolte as a romantically obsessed painter, and Paul Schrader's 1997 familial-angst drama "Affliction," with Nolte as a son burdened by his father's extremes. By the dawn of the 2000s, years of hard living had so dramatically altered Nolte's appearance that he was sufficiently weathered to become a full-on character actor, a suitable lane for his offbeat instincts. (Example: His wild performance as a grizzled Vietnam vet in 2008's scathing Hollywood satire "Tropic Thunder.") Not all of Nolte's latter-day experiments are compelling, but he remains a force, as demonstrated by the Oscar nomination he scored for his supporting role in the 2012 sports drama "Warrior." FYI, his two previous nods were for "The Prince of Tides" and "Affliction." Noonan, Tom. Actor/filmmaker, b. 1951. At six and a half feet tall, with forlorn features and a lean physique, Noonan makes an indelible impression before he opens his mouth. And when he does, the most unexpected things come out—he consistently belies expectations, whether adding heartfelt notes to his unforgettable turn as a serial killer in "Manhunter" (1986) or adding humor to his role as a reckless scientist in "Eight Legged Freaks" (2002). In fact, Noonan is often the most interesting while playing undefinable roles. In 1995's "Heat," Noonan's a one-scene wonder as a wheelchair-bound technician adept at nabbing digital information; and in Noonan's directorial debut, 1994's "What Happened Was...," he captures every uncomfortable nuance of an everyman on a first date with a sexy coworker. A firm believer in the do-it-yourself aesthetic, Noonan has written, directed, produced, edited, and even scored his own films, which also include "The Wife" (1995) and "Wang Dang" (1999). Of late, TV has kept Noonan busy, with long runs on "Damages" (from 2009 to 2011), "Hell on Wheels" (2011-2014), and "12 Monkeys" (2015-2018) complementing guest shots on other shows as well as continued feature work. “Nosferatu the Vampyre” aka “Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht” (1979). This soulful remake of the F.W. Murnau classic fits nicely into helmer Werner Herzog’s bizarro canon. Featuring the director’s alter ego/bete noire Klaus Kinski as a ghoulish corpse of a bloodsucker with pallid skin and reptilian fangs, the movie is a loose adaptation of Bram Stoker’s novel “Dracula,” as was Murnau’s unauthorized version. And even though Herzog provides a few creepy bits, especially a sequence of rampaging vermin that reputedly got him chased out of the Netherlands for releasing too many rats into the city of Delft, he’s much more interested in the anguish of his characters and, as always, the terrible beauty of the natural world. Accordingly, the most memorable things about the movie are the suffocating ennui that grips Kinski’s vampire from start to finish, and the lyrical outdoors passages set to unsettling music by regular Herzog collaborators Popol Vuh. The climax, in which leading lady Isabelle Adjani attempts to seduce her tormentor into self-destruction, is a typically strange Herzog moment that veers from prurient to philosophical to pathetic. (German- and English-language versions of the movie were shot simultaneously, hence the alternate titles.) Olmos, Edward James. Actor/director, 1947. After a brief music career during his high-school and college years, Olmos transitioned to acting, sharpening his skills with stage work and minor film/TV roles before defining his onscreen persona with several splashy roles in the early '80s. Wiry and intense, with rough features and an intimidating gravitas, Olmos was a charismatic but menacing figure in "Zoot Suit" (1981), a wild-eyed Native American in "Wolfen" (also 1981), an enigmatic cop in "Blade Runner" (1982), and an inspiring outlaw in "The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez" (1982). He then secured his fame with a 1984-1989 run on the stylish TV series "Miami Vice" as mysterious squad leader Martin Castillo; his distinctive work netted him an Emmy and a Golden Globe. Before the series was off the air, Olmos added an Oscar nomination to his resume for his uplifting performance as an inner-city teacher in "Stand and Deliver" (1988). And though he continues to show versatility and curiosity, Olmos has remained true to the persona he established in the '80s, playing principled characters with deep resolve. He portrayed a Supreme Court nominee in a powerful first-season episode of "The West Wing," and the patriarch of a Mexican-American clan in the miniseries "American Family" (2002). Then, from 2003 to 2009, he incarnated the grim but humane Commander Adama on the TV series "Battlestar Galactica," anchoring the provocative sci-fi reboot with a memorably intense performance. Olmos' directing oeuvre, which reflects his offscreen social concerns, includes the 1992 feature "American Me," about gangs and prisons, and the 2006 telefilm "Walkout," about an important Latin-American student demonstration. "On a Clear Day" (2005). Frank (Peter Mullan) is a British shipbuilder who's just been put out to pasture. Realizing he devoted his career to a company that has no further use for him, he feels uprooted from his own life. His friends worry for his sanity and his wife (Brenda Blethyn) frets about the solvency of their long marriage. So when Frank decides the way to put meaning back into his existence is to swim the English Channel, those around him don't know whether to panic or cheer. Viewers will have no such ambivalence, because in Gaby Dellal's rousing movie, Frank's audacious challenge becomes a potent metaphor for taking the reins of one's own destiny. Dellal and screenwriter Alex Rose take their time establishing characters and laying the groundwork for Frank's adventure, touching on flavors ranging from sharp social drama to silly physical comedy along the way. By the time Frank's big swim comes around, it's hard not to feel completely invested in his endeavor. “One Day in September” (1999). Recounting the horrific events of the 1972 Munich Olympics with an eye for detail and suspense, director Kevin Macdonald’s taut documentary investigates what happens when fanatics clash with bureaucrats. After depicting how Palestinian terrorists brutally abducted a group of Israeli athletes, covering ground that’s familiar from clips such as the ABC Sports reports he features, Macdonald comes into his own analyzing the disaster that happened at the Munich airport when German authorities tried to contain the situation. Letting facts point fingers so he doesn’t have to, Macdonald and his collaborators use tools including 3-D graphics to lay out exactly what went wrong. Most striking of all is an interview with the sole surviving terrorist, filmed in his unnamed African hideaway, which adds a predictably contrary viewpoint. "The Outlaw Josey Wales" (1976). The meshing of two distinct sensibilities makes this rich adventure unique among Clint Eastwood's Westerns. Inquisitive writer-director Philip Kaufman contributed to the screenplay and directed a few scenes before Eastwood took over, so pieces of the movie are filmed with Kaufman's sly imagination even though most of it is shot in Eastwood's rigorously efficient style. Parsing who did what is less interesting than diving into the result of the testy collaboration, because though "Josey Wales" is driven by a straightforward revenge plot, it's got the meandering rhythms and memorable details of a road movie. As the titular gunman makes his way West, he reluctantly attracts a family of misfits who need his protection as much as he needs their companionship. The action stuff is great, from the brutal violence that kicks the story into gear to the various bits of Eastwood kicking ass, but it's the softer colors that resonate—the title character's habit of spitting for emphasis, the avuncular charm of aged Lone Watie (Chief Dan George), the stoic dignity of Ten Bears (Will Sampson), the amusing sass of Grandma Sarah (Paula Trueman). "Overnight" (2003). Meet Troy Duffy, asshole. In the late '90s, swaggering twentysomething Duffy nabbed the proverbial brass ring of show business. Hollywood bought his script "The Boondock Saints" and hired him to direct, his band scored a major-label deal, and he got meetings with heavy-duty players. So why haven't you heard of Duffy? As this screed-cum-documentary painfully details, he alienated everyone in his path with his loutish arrogance. So even though "Saints" hit theaters in 1999 with Willem Dafoe heading a respectable cast, Duffy had already squandered his moment. Behind-the-scenes footage taped by friends eager to document Duffy's ascension gets repurposed as incriminating evidence in "Overnight," which makes up for in jaw-dropping content what it lacks in technical sophistication. It's staggering to watch an overbearing tyro outdo Hollywood smoothies in terms of rudeness and delusional thinking, even if the motivation behind this doc is just as skin-crawling as Duffy's misbehavior. But, as Duffy learned the hard way, payback's a bitch. A-C D-F G-I J-L M-O P-R S-U V-Z home • news • books and movies • field guide • services • journalism • gallery • bio

"The Mask of Fu Manchu" (1932). A nasty piece of business featuring the always entertaining Boris Karloff as Sax Rohmer's Asian mastermind, this thoroughly un-p.c. programmer teems with black-and-white images so shimmering they seem to be made of mercury. The plot is of course ludicrous and forgettable, nonsense about treasure hunters and a vengeful arch-criminal, so it's the creepy vibe that lingers. Karloff's look as Fu Manchu is otherworldly, a cross between Mr. Spock and Anton LeVay, and Myrna Loy (!) is equally striking as the villain's offspring. (In one memorable bit, Karloff dismisses Loy with his mellifluous line "Pay no mind to my insignificant daughter.") Presenting a truly cruel and unusual baddie brought to life by outlandish casting, "Fu Manchu" is an essential entry in any worthwhile Karloff-a-thon.

"The Mask of Fu Manchu" (1932). A nasty piece of business featuring the always entertaining Boris Karloff as Sax Rohmer's Asian mastermind, this thoroughly un-p.c. programmer teems with black-and-white images so shimmering they seem to be made of mercury. The plot is of course ludicrous and forgettable, nonsense about treasure hunters and a vengeful arch-criminal, so it's the creepy vibe that lingers. Karloff's look as Fu Manchu is otherworldly, a cross between Mr. Spock and Anton LeVay, and Myrna Loy (!) is equally striking as the villain's offspring. (In one memorable bit, Karloff dismisses Loy with his mellifluous line "Pay no mind to my insignificant daughter.") Presenting a truly cruel and unusual baddie brought to life by outlandish casting, "Fu Manchu" is an essential entry in any worthwhile Karloff-a-thon.

McDowell, Malcolm. Master of menace, b. 1943. Playing a grinning sociopath in Stanley Kubrick’s “A Clockwork Orange” (1973) pretty much damned prolific Brit McDowell to a career playing heavies, and tepid response to his rare deviations from typecasting sealed his fate. So now, decades after leading his pals through “a bit of the old ultraviolence,” McDowell reigns as one of the most reliably malevolent figures in international cinema. His affinity for darkness apparently stems from the rough childhood he spent with an abusive father, and McDowell himself went through a number of bleak years marked by womanizing and substance abuse. Undoubtedly to the versatile actor’s great frustration, most of his nice-guy performances, such as his nimble portrayal of an adventuresome H.G. Wells in “Time After Time” (1979), have been forgotten by all but devoted fans. Instead, he’s largely known for incarnating killers like Gaius Germanicus Caesar, the debauched emperor in “Caligula” (1979); Cochrane, the bloodthirsty pilot determined to down a fellow flyer in “Blue Thunder” (1983); and Dr. Soran, the space-age baddie who offs Captain Kirk in “Star Trek: Generations” (1994). His personal rogues gallery is so endless that even when he plays less arch antagonists like Teddy K, the corporate titan of “In Good Company” (2004), or Fox News patriarch Rupert Murdoch in “Bombshell” (2019), he brings so much baggage that he’s creepy from the moment he walks onscreen. Yet buried in the glowering and ranting is a performer with consummate charm, elegant bearing, and a peculiar sort of romantic appeal. On the rare occasions when he dodges assignments in schlock and seizes opportunities to essay dimensional roles, the considerable gifts that audiences have spent years taking for granted quickly come into focus. McGill, Bruce. Actor, b. 1950. Anyone who can get laughs playing a crazed frat rat in a raucous comedy and then singe the screen as a thundering litigator in a topical drama, all while exuding the petulant charisma that makes him so unique, is tops in my book. McGill, who hit those aforementioned heights as D-Day in "Animal House" (1978) and as Mississippi lawyer Ron Motley in "The Insider" (1999), is like a designated hitter: Whether he's got one scene or a hundred, he slams every line thrown his way out of the park. He also has a great gift for blending into the fabric of any movie, so he slips easily from the broad comedy of "Legally Blonde 2" (2003) to the old-fashioned drama of "Cinderella Man" (2005). In the former, he's riotous as a pompous Senator learning to embrace his dog's homosexuality, and in the latter, he's a pennywise promoter who holds the fate of the title character in his oily hands. Often featured as belligerent authority figures and even sometimes as rednecks—he's the cop whose apprehension of two innocent kids kicks off the story of "My Cousin Vinny" (1992)—McGill seems capable of doing just about anything, and the subtle way he autographs every performance is like a friendly wink telling viewers he's always in on the joke. Consider, for instance, his memorable turn as a cranky Elvis impersonator in the John Landis lark “Into the Night” (1985). McGill has also notched steady work on TV, appearing as a recurring character on “MacGyer” (from 1986 to 1989, with a 2017 appearance on the reboot show) and as a series regular on “Rizzoli & Isles” (from 2010 to 2016).

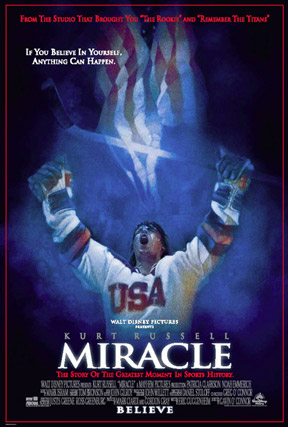

McGill, Bruce. Actor, b. 1950. Anyone who can get laughs playing a crazed frat rat in a raucous comedy and then singe the screen as a thundering litigator in a topical drama, all while exuding the petulant charisma that makes him so unique, is tops in my book. McGill, who hit those aforementioned heights as D-Day in "Animal House" (1978) and as Mississippi lawyer Ron Motley in "The Insider" (1999), is like a designated hitter: Whether he's got one scene or a hundred, he slams every line thrown his way out of the park. He also has a great gift for blending into the fabric of any movie, so he slips easily from the broad comedy of "Legally Blonde 2" (2003) to the old-fashioned drama of "Cinderella Man" (2005). In the former, he's riotous as a pompous Senator learning to embrace his dog's homosexuality, and in the latter, he's a pennywise promoter who holds the fate of the title character in his oily hands. Often featured as belligerent authority figures and even sometimes as rednecks—he's the cop whose apprehension of two innocent kids kicks off the story of "My Cousin Vinny" (1992)—McGill seems capable of doing just about anything, and the subtle way he autographs every performance is like a friendly wink telling viewers he's always in on the joke. Consider, for instance, his memorable turn as a cranky Elvis impersonator in the John Landis lark “Into the Night” (1985). McGill has also notched steady work on TV, appearing as a recurring character on “MacGyer” (from 1986 to 1989, with a 2017 appearance on the reboot show) and as a series regular on “Rizzoli & Isles” (from 2010 to 2016). "Miracle" (2004). Seeing as how patriotism and sports are two things I generally don't go for in movies, it's surprising how much I dig this rousing drama about the 1980 U.S. Olympic hockey team. Director Gavin O'Connor cast real skaters as most of the players, and the credibility they bring to scenes on and off the ice is palpable. Leading the team is Kurt Russell, in one of those rare dramatic performances that reveals the largely untapped depths of his talent. Packed into tacky period clothes and speaking in the flat parlance of the Midwest, he transforms into a full-blooded character more than he has in any movie since "Elvis" back in 1979; no matter how many times I see him bark "It's yer time!" to his players, I still find the moment inspiring. While the movie is only moderately effective at conveying the political backdrop that made the team's historic win so exciting, the game scenes unfold with breathless energy, and the shorthand used to make both the individual players and the team sympathetic works wonders. "Miracle" doesn't reinvent the underdog sports movie any more than, say, "Hoosiers" (1986), but it's a great example of how a terrific movie can make a tired genre feel utterly fresh.

"Miracle" (2004). Seeing as how patriotism and sports are two things I generally don't go for in movies, it's surprising how much I dig this rousing drama about the 1980 U.S. Olympic hockey team. Director Gavin O'Connor cast real skaters as most of the players, and the credibility they bring to scenes on and off the ice is palpable. Leading the team is Kurt Russell, in one of those rare dramatic performances that reveals the largely untapped depths of his talent. Packed into tacky period clothes and speaking in the flat parlance of the Midwest, he transforms into a full-blooded character more than he has in any movie since "Elvis" back in 1979; no matter how many times I see him bark "It's yer time!" to his players, I still find the moment inspiring. While the movie is only moderately effective at conveying the political backdrop that made the team's historic win so exciting, the game scenes unfold with breathless energy, and the shorthand used to make both the individual players and the team sympathetic works wonders. "Miracle" doesn't reinvent the underdog sports movie any more than, say, "Hoosiers" (1986), but it's a great example of how a terrific movie can make a tired genre feel utterly fresh. "Movie Time." Several excellent books have provided timelines for the first century of movies, notably DK Publishing's behemoth "Chronicle of the Cinema." Offering breezy readability as an alternative to the DK tome's shelf-breaking inclusiveness, Gene Brown's "Movie Time" is one of the most enjoyable examples of the genre. Attractively designed with expertly selected photos and enough negative space to keep the onslaught of information from seeming overwhelming, the book devotes about five pages to each year from 1927 to 1994, which shorter sections exploring the years comprising the silent era. Each segment opens with a brief overview and a list of key facts, such as box-office toppers and award winners, then delves into month-by-month descriptions of births, deaths, movie openings, and other notable events. The sum effect provides context for things that seem insulated in other cinema guides. Instead of discussing 1939's "His Girl Friday" as simply a Cary Grant movie or a screwball comedy, for instance, "Movie Time" situates the picture in a year defined by Louella Parsons' acid tongue and Laurence Olivier's hot temper. Because each entry in the book is so brief, "Move Time" works best as a complement to other texts, notably Ephraim Katz' "The Film Encyclopedia." Used in concert with other books or enjoyed on its own merits, "Movie Time" is so addictively enjoyable that it's a shame subsequent editions never materialized.

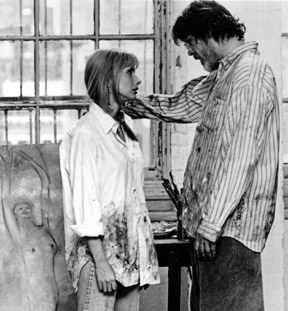

"Movie Time." Several excellent books have provided timelines for the first century of movies, notably DK Publishing's behemoth "Chronicle of the Cinema." Offering breezy readability as an alternative to the DK tome's shelf-breaking inclusiveness, Gene Brown's "Movie Time" is one of the most enjoyable examples of the genre. Attractively designed with expertly selected photos and enough negative space to keep the onslaught of information from seeming overwhelming, the book devotes about five pages to each year from 1927 to 1994, which shorter sections exploring the years comprising the silent era. Each segment opens with a brief overview and a list of key facts, such as box-office toppers and award winners, then delves into month-by-month descriptions of births, deaths, movie openings, and other notable events. The sum effect provides context for things that seem insulated in other cinema guides. Instead of discussing 1939's "His Girl Friday" as simply a Cary Grant movie or a screwball comedy, for instance, "Movie Time" situates the picture in a year defined by Louella Parsons' acid tongue and Laurence Olivier's hot temper. Because each entry in the book is so brief, "Move Time" works best as a complement to other texts, notably Ephraim Katz' "The Film Encyclopedia." Used in concert with other books or enjoyed on its own merits, "Movie Time" is so addictively enjoyable that it's a shame subsequent editions never materialized. "New York Stories" (1989). As with most anthology films, "New York Stories"—featuring vignettes by Woody Allen, Francis Ford Coppola, and Martin Scorsese—isn't consistently entertaining. The best sequence is Scorsese's "Life Lessons," screenwriter Richard Price's second collaboration with the great director (following 1986’s "The Color of Money"). Nick Nolte plays an asshole artist romantically obsessed with untalented wannabe Rosanna Arquette, and the piece brims with the energy of two inventive actors blasting through smart material. Neither character is particularly sympathetic, but that never stopped Scorsese before, and the director has a ball with swishing camera moves and even wink-wink devices like an iris in to a sexy detail. While Allen's segment, "Oedipus Wrecks," is an amusing piffle taking the stereotype of the overbearing Jewish mother to cartoonish extremes, that piece is very much in the Woodman's wheelhouse, whereas "Life Lessons" is less typical of Scorsese's offerings and thus of greater interest. As for the Coppola contribution, the best one can say is that it’s shot well by frequent Coppola collaborator Vittorio Storaro.

"New York Stories" (1989). As with most anthology films, "New York Stories"—featuring vignettes by Woody Allen, Francis Ford Coppola, and Martin Scorsese—isn't consistently entertaining. The best sequence is Scorsese's "Life Lessons," screenwriter Richard Price's second collaboration with the great director (following 1986’s "The Color of Money"). Nick Nolte plays an asshole artist romantically obsessed with untalented wannabe Rosanna Arquette, and the piece brims with the energy of two inventive actors blasting through smart material. Neither character is particularly sympathetic, but that never stopped Scorsese before, and the director has a ball with swishing camera moves and even wink-wink devices like an iris in to a sexy detail. While Allen's segment, "Oedipus Wrecks," is an amusing piffle taking the stereotype of the overbearing Jewish mother to cartoonish extremes, that piece is very much in the Woodman's wheelhouse, whereas "Life Lessons" is less typical of Scorsese's offerings and thus of greater interest. As for the Coppola contribution, the best one can say is that it’s shot well by frequent Coppola collaborator Vittorio Storaro.

“The Night of the Hunter” (1955). Groundbreaking in its use of fairy-tale devices to tell a decidedly adult story, the sole directorial effort of acting great Charles Laughton features some of the most haunting images of ’50s cinema. Robert Mitchum plays a faux preacher who marries a widow, kills her, and then stalks her children because he’s sure someone in the family knows the location of stolen loot. Laughton employs arty camera angles straight out of the Murnau playbook, then fills those angles with nightmare visions like a switchblade blasting erotically out of Mitchum’s pocket. The movie also contains the famous bit in which Mitchum arm-wrestles himself, one hand tattooed “L-O-V-E” and the other “H-A-T-E,” while delivering a cornpone parable. Adapted from Davis Grubb’s novel by lit legend James Agee, whose script Laughton reputedly rewrote, the movie suffers for its lack of irony, because Laughton presents even the hoariest elements with a straight face. Still, that utter committment to narrative sincerity, credibility be damned, is a big part of what makes the movie singular. And even though costars Lillian Gish and Shelley Winters acquit themselves nicely, the picture is Mitchum’s from start to finish. Whether preachin’, singin’, or killin’, he’s a vision of Southern spirituality turned utterly psychotic. Oates, Warren. Actor, 1928-1982. Originally a stuntman and bit player, Oates became a familiar figure in TV westerns of the 1960s before earning immortality with roles in a string of disturbing films, especially "The Wild Bunch" (1969), "Two Lane Blacktop" (1971), "Dillinger" (1973), "Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia" (1974), and the notorious "Cockfighter" (1974). A small, swarthy man with a clenched fist of a face, Oates practiced a persuasively naturalistic style of acting in roles calling for copious perspiration, unrepentant scowling, and superhuman levels of irascibility. Usually encountered in flagrante delicto with a cheap woman, a loaded gun, and free-flowing liquor, often in tandem, Oates nonetheless brought a distinctive brand of gallows humor to his ill-fated characters. Truly one of the unique screen personas of the New Hollywood era, he was the perfect muse for idiosyncratic directors Monte Hellman and "Bloody" Sam Peckinpah. And if some mainstream movie fans know him best as Sgt. Hulka, the belligerent NCO in comedy smash "Stripes" (1981), that’s a testament to Oates’ underrated versatility. One wonders what areas he might have explored given more years on the planet.

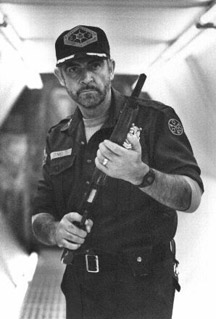

Oates, Warren. Actor, 1928-1982. Originally a stuntman and bit player, Oates became a familiar figure in TV westerns of the 1960s before earning immortality with roles in a string of disturbing films, especially "The Wild Bunch" (1969), "Two Lane Blacktop" (1971), "Dillinger" (1973), "Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia" (1974), and the notorious "Cockfighter" (1974). A small, swarthy man with a clenched fist of a face, Oates practiced a persuasively naturalistic style of acting in roles calling for copious perspiration, unrepentant scowling, and superhuman levels of irascibility. Usually encountered in flagrante delicto with a cheap woman, a loaded gun, and free-flowing liquor, often in tandem, Oates nonetheless brought a distinctive brand of gallows humor to his ill-fated characters. Truly one of the unique screen personas of the New Hollywood era, he was the perfect muse for idiosyncratic directors Monte Hellman and "Bloody" Sam Peckinpah. And if some mainstream movie fans know him best as Sgt. Hulka, the belligerent NCO in comedy smash "Stripes" (1981), that’s a testament to Oates’ underrated versatility. One wonders what areas he might have explored given more years on the planet. "Outland" (1983). Of the films released in the post-"Star Wars" sci-fi boom, Peter Hyams' "Outland" may well have been the most brazen. It's "High Noon" (1952) in space, with such fidelity to its inspiration that one wonders how litigation was avoided. As with many of Hyams' pictures, logic takes a backseat to suspense, but "Outland" has a secret weapon in its supporting cast: Frances Sternhagen, playing the quintessential crotchety small-town doc who simply happens to be working in a mining facility on one of Jupiter's moons. Sean Connery—casually cool in his post-Bond, pre-Oscar wilderness years—plays the Gary Cooper part, a sheriff who tries to rouse the residents of a sleepy community into siding with him when it becomes known that a killer is a-comin'. The plot is twisty business about an evil middle manager (Peter Boyle) drugging his workers to jack up productivity, but what really matters are Sternhagen's winning interplay with Connery and the gorgeous visuals. Hyams blends gritty sets inspired by "Alien" with wondrous exterior shots in the vein of "2001" to create a palpable sense of place.

"Outland" (1983). Of the films released in the post-"Star Wars" sci-fi boom, Peter Hyams' "Outland" may well have been the most brazen. It's "High Noon" (1952) in space, with such fidelity to its inspiration that one wonders how litigation was avoided. As with many of Hyams' pictures, logic takes a backseat to suspense, but "Outland" has a secret weapon in its supporting cast: Frances Sternhagen, playing the quintessential crotchety small-town doc who simply happens to be working in a mining facility on one of Jupiter's moons. Sean Connery—casually cool in his post-Bond, pre-Oscar wilderness years—plays the Gary Cooper part, a sheriff who tries to rouse the residents of a sleepy community into siding with him when it becomes known that a killer is a-comin'. The plot is twisty business about an evil middle manager (Peter Boyle) drugging his workers to jack up productivity, but what really matters are Sternhagen's winning interplay with Connery and the gorgeous visuals. Hyams blends gritty sets inspired by "Alien" with wondrous exterior shots in the vein of "2001" to create a palpable sense of place.