peter hanson's field guide to interesting film

"Paris, Texas" (1984). Pure poetry. As soon as grizzled Travis (Harry Dean Stanton) wanders out of the scorching Texas desert to the fluid sounds of Ry Cooder's slide-guitar score, "Paris, Texas" creates a reflective mood that never fades, even as the story moves from sadness to comedy to bitter regret. The Sam Shepard/L.M. Kit Carson script tells an enigmatic story about a man slowly rediscovering his traumatic past and trying to repair the damage he caused in his wild years. Shepard and director Wim Wenders take their time, so the movie sprawls over an excessive 147 minutes, but it's hard to peg any moments to cut—just when you think a monologue or a slow-burning plot device has overstayed its welcome, the story veers off to someplace unexpected and potent. And the idea of losing even a frame of Robby Muller's spectacular photography is chilling; his desertscapes virtually radiate heat, and he finds remarkable compositions in such unexpected locations as a highway overpass and the dank rooms of a sex club. Stanton, so ubiquitous a character player that it's easy to take him for granted, offers what may be his most textured performance, and Nastassja Kinski's tense bewilderment is captivating. Hunter Carson, Aurore Clement, and Dean Stockwell, all wonderful, round out the principal cast. "Paris, Texas" is slow going, but like the aqueous sound of Cooder's guitar, the movie has an impact that sneaks up on you.

"Passion Fish" (1992). "I didn't ask for the anal probe." Discovering just how this unlikely dialogue figures into John Sayles' engaging dramedy is part of what makes the movie so surprising and delightful. As with all of Sayles' pictures, complex characters drive this story about a soap star brought down to earth by paralysis, and the relationship between diva May-Alice (Mary McDonnell) and nurse Chantelle (Alfre Woodard) is one of the richest in Sayles' celebrated filmography. Quickly moving past clichés and digging into rich character histories and vivid behaviors, Sayles makes his story of recovery and redemption feel new and immediate. He also fills the movie with humid Louisiana atmosphere, because after a life-changing accident, May-Alice flees New York to hide in the bayou country of her youth. Concurrent with her deepening relationship with her nurse, May-Alice discovers the many pleasures of her home state, not the least of which is charming Rennie (played by Sayles regular David Strathairn), her high-school crush. In lesser hands, any one of these story elements could turn maudlin or strident, but with Sayles at the helm, "Passion Fish" is never anything but warm and humanistic.

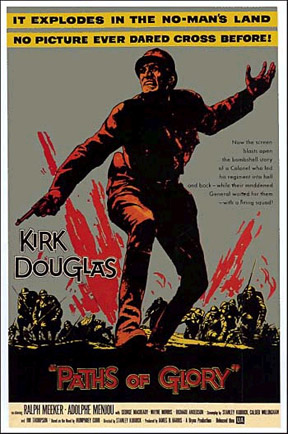

"Paths of Glory" (1957). Arguably Stanley Kubrick's first masterpiece, "Paths of Glory" has a great deal in common thematically with his better known work. Furthermore, the picture's meticulous photography bears his unmistakable stamp. However, something important separates "Paths of Glory" from most of Kubrick's subsequent output. At a taut 87 minutes, the film has an economy that Kubrick approached only once more, with the all-killer/no-filler "Dr. Strangelove" in 1964. The difference is that "Strangelove" moves briskly because it's a comedy, whereas "Paths of Glory" is Kubrick's last drama to make its point and leave the stage, rather than lingering on spectacle or venturing into provocative tangents. A ferocious tale about the fate of several WWI French soldiers used as patsies to deflect culpability for an ill-fated assault, the picture is half war story, half courtroom drama. Kirk Douglas, at his righteously indignant best, plays the ambitious officer who defends the soldiers, and his scenes speaking truth to power are scalding. Often remembered for the innovative tracking shots that Kubrick used to capture life in the trenches, the movie is nearly flawless in terms of dramaturgy and techical execution, signaling how quickly Kubrick had evolved from a promising newcomer to an important auteur.

"Paths of Glory" (1957). Arguably Stanley Kubrick's first masterpiece, "Paths of Glory" has a great deal in common thematically with his better known work. Furthermore, the picture's meticulous photography bears his unmistakable stamp. However, something important separates "Paths of Glory" from most of Kubrick's subsequent output. At a taut 87 minutes, the film has an economy that Kubrick approached only once more, with the all-killer/no-filler "Dr. Strangelove" in 1964. The difference is that "Strangelove" moves briskly because it's a comedy, whereas "Paths of Glory" is Kubrick's last drama to make its point and leave the stage, rather than lingering on spectacle or venturing into provocative tangents. A ferocious tale about the fate of several WWI French soldiers used as patsies to deflect culpability for an ill-fated assault, the picture is half war story, half courtroom drama. Kirk Douglas, at his righteously indignant best, plays the ambitious officer who defends the soldiers, and his scenes speaking truth to power are scalding. Often remembered for the innovative tracking shots that Kubrick used to capture life in the trenches, the movie is nearly flawless in terms of dramaturgy and techical execution, signaling how quickly Kubrick had evolved from a promising newcomer to an important auteur.

"Payday" (1972). If you only know Rip Torn as the irascible character player from "Men in Black" (1997) and countless other movies, brace yourself for his terrifying performance in "Payday," one of the most relentless character pictures ever made. A fast, mean story about a monstrous country singer named Maury Dann (Torn), Daryl Duke's movie portrays its lead character as some kind of demon loosed on an unsuspecting earth. Plowing through women, friends, relatives, fans, and anybody else who crosses his path, Dann is on a rampage throughout the entire movie, using rage and intimidation to cow anyone not sufficiently deferential to his notoriety. Dann is such an extreme sort that the movie quickly goes beyond music-industry satire, becoming a blistering treatise on unrestrained megalomania. Think of it as what might have happened if Sam Peckinpah had directed "Tender Mercies" (1983)—in other words, don't expect anything tender or merciful.

Peak, Bob. Artist, 1927-1992. A painter whose dreamy airbrush style was often best suited to fantasy films, Peak created some of the most tantalizing movie posters of the '70s and '80s. After making his mark with a more traditional illustration style on several key '60s posters, Peak hit his groove in the mid-'70s, crafting magical images including his breathtaking shot for "Superman: The Movie" (1978), which features a metallic "S" logo and a colorful streak amid lush clouds. Like many of his best offerings, the "Superman" one-sheet promised wonder while retaining mystery. Peak did equally memorable work for a wide variety of films, contributing the brooding, blood-red key art for "Apocalypse Now" (1979); the shimmering collages that sold several "Star Trek" pictures; and even muscular images for Clint Eastwood's orangutan flicks. Like Richard Amsel, Peak also did a great deal of editorial and advertising work, including a flotilla of "TV Guide" covers.

Petersen, William L. Actor/producer, b. 1953. Petersen popped onscreen to deliver one line in Michael Mann's "Thief" (1981), shot in his hometown of Chicago, then returned to his theater roots until another great director took notice. In the William Friedkin bio "Hurricane Billy," Petersen tells an amusing story of how Friedkin cast the actor in "To Live and Die in L.A." (1985) seemingly on a whim, adding Petersen's pal John Pankow to the cast with equal abruptness. Despite his offbeat transition from stage to screen, Petersen displayed a commanding presence in "L.A.," strutting through the movie on his bowed legs like he'd already been a superstar for years. He then struck a different note in "Manhunter" (1986), playing a cop as tortured and sensitive as his "L.A." federal agent was cocky and cruel. Another terrific leading role followed, with Petersen playing an endearingly boozy ballplayer in the telefilm "Long Gone" (1987). But then, perhaps because none of these projects drew massive audiences, Petersen split much of his subsequent time between small projects and small roles. Things changed in 2000, when he teamed with Jerry Bruckheimer to produce the series "CSI: Crime Scene Investigation," which became a massive hit and finally turned Petersen, who played the leading role of troubled investigator Gil Grissom, into a household name. Petersen toplined the show from 2000 to 2008, then appeared sporadically through to the 2015 finale. Presumably set for life on the cash he earned making “CSI,” Petersen has kept a comparatively low profile since leaving the series, balancing a return to stage work with occasional appearances in movies and TV shows.

“Pickup on South Street” (1953). The type of lean and efficient work upon which Samuel Fuller’s notoriety is built, “Pickup on South Street” is 80 minutes of pure noir bliss, even though it goes awfully soft at the end. Archetypal big-city thug Richard Widmark gives one of his tastiest performances as Skip McCoy, a low-rent pickpocket who inadvertently swipes microfilm containing stolen U.S. government secrets from a mark on the New York subway. Turns out she was unknowingly ferrying the film for a ring of Russian-employed spies. This simple set-up leads to a delicious dance of underworld operators, as McCoy tries to parlay his unexpected treasure into a huge payday, no matter the danger his actions represent for the good ol’ U.S. of A. Widmark’s childlike glee at frustrating the police, and his ruthless drive to squeeze the Reds for all they’re worth, are pure pleasure to behold. The love story involving Widmark and the gorgeous dame from whom he originally stole the film is contrived at best, but a subplot involving a colorful stool pigeon (Thelma Ritter) provides endless amounts of humor and pathos. Screenwriter/director Fuller’s plotting is nearly flawless, and his claustrophobic camera angles suggest a grimy underworld existing in between the molecules of everyday Manhattan.

“Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood.” An essential volume of film history and also a page-turning drama about a key chapter in the evolution of the American film industry, Mark Harris’ 2008 nonfiction bestseller is the literary equivalent of crack for fans of the New Hollywood era. Offering a prequel of sorts to Peter Biskind’s equally entertaining “Easy Riders, Raging Bulls,” Harris meticulously tracks the creation of 1967’s five Best Picture nominees: “Bonnie and Clyde,” “Doctor Dolittle,” “The Graduate,” “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” and “In the Heat of the Night.” These movies signify the clash between studio-era stodginess and the brash, European-influenced ideas of young actors, cinematographers, directors, producers, and screenwriters who started emerging the mid-’60s. Harris’ storytelling is impeccable, sticking with subplots until they pay off while also creating tension through slow-burn narrative elements and illuminating intercutting. More impressively, his research is astonishing, giving readers not only fresh perspectives on familiar characters (Warren Beatty, Mike Nichols) but important insights into behind-the-scenes players like producer Arthur P. Jacobs, screenwriter Stirling Stilliphant, cinematographer Haskell Wexler, and many more.

Platt, Oliver. Actor, b. 1960. With his expansive frame, jet-black hair, and impossibly square face, Platt cuts an offbeat picture—especially when performing one of the spellbinding meltdowns that are his specialty. He’s made an art form of exasperation since his breakout role in 1990’s “Flatliners,” in which he provided sarcastic commentary during a journey to the great beyond. Possessing infallible comic timing and an endearing willingness to humiliate himself for the sake of a laugh, Platt is often at his best when his characters are at their worst. In his Emmy-nominated run as shameless litigator Russell Tupper on the cable series “Huff” (2004-2006), Platt makes the dissipation of an addict as funny as it is tragic, whether he’s flipping off a snake or freaking out because of ingrown hairs on his scrotum. Frequently relegated to best-friend roles or slotted into ensemble casts as a go-to funnyman, Platt has tried to break through as a leading man (e.g., 1995’s “Funny Bones”) with little success. Yet he still boasts a varied résumé, with credits both incidental (his small part as a cranky geek summoned to action in 1996’s “Executive Decision”) and impressive (his recurring role as a tart-tongued White House counsel in “The West Wing”).

Plummer, Amanda. Actor, b. 1957. To understand Plummer’s exceptional versatility, look at the divide between three of her most distinctive roles. In one of her earliest movies, “The World According to Garp” (1981), she plays a heartbreaking cameo as a mute abuse victim appalled by extreme acts taken in her name. Then in her breakout picture, “The Fisher King” (1991), she does nothing but talk as a lonely flibbertigibbet. And finally in “Pulp Fiction” (1994), Plummer is a foul-mouthed wannabe crook with the unlikely moniker of Honey Bunny. The through-line connecting these disparate roles is that Christopher Plummer’s daughter excels at playing people on the fringe of society, whether by dint of unfortunate circumstance, mental infirmity, or simple insecurity. But if it sometimes seems she’s typecast as oddballs, don’t cry for Plummer. She’s got a shelf filled with awards, including three Emmys and a slew of theatrical prizes, to demonstrate her status among her peers.

“The Pope of Greenwich Village” (1984). A tall, cool glass of Martin Scorsese Lite, this character piece about lowlife losers is suffused with authentic downtown flavors. Eric Roberts and Mickey Rourke, ironically both hard-luck cases who squandered their considerable gifts offscreen, play a wannabe gangster and his only slightly more together cousin. The plot about their conspiracy to rip off the mob is standard stuff, but the character work is extraordinary. Novelist-screenwriter Vincent Patrick decorates every scene with credible details, putting viewers squarely in the middle of the dark coffee shops, grimy alleys, and moldy warehouses of lower Manhattan. Patrick’s work is enlivened by a spectacular cast, from the aforementioned leads to powerhouse supporting players Jack Kehoe, Kenneth McMillan, Geraldine Page, M. Emmet Walsh, and Burt Young, all of whom are perfectly cast as the sort of streetwise strivers one finds only in New York City. Journeyman director Stuart Rosenberg keeps things moving at a fast clip without losing the script’s humanistic focus, even if the film is undercut by an anticlimactic ending and an undernourished subplot concerning Rourke’s he-man mistreatment of his girlfriend (Daryl Hannah).

"Pretty Poison" (1968). A pitch-black thriller with comic flair and ingenious casting, this candy-colored '60s oddity is nearly as disturbing as that other Anthony Perkins movie about a psycho. Perkins plays Dennis, a disturbed young man who accidentally killed a relative when he was a teenager. Now out on probation, he entertains a vivid fantasy life while trying to find his place in a small Massachusetts town. Then Dennis meets high-school majorette Sue Ann (Tuesday Weld), who believes his tall tales about being a CIA agent, and they form an unbreakable romantic bond. Things don't go well for people in their town after that happens. Perkins undercuts his image perfectly with a fragile, sympathetic performance, and Weld is a powerhouse as she transforms from seeming innocent to pathological seductress. Director Noel Black contributes zippy pacing and clever '60s camerawork, while screenwriter Lorenzo Semple Jr. (adapting a Stephen Geller novel) moves the story along with tremendous momentum and sly wit. Watch for the nervy thematic interplay of sex and violence, and listen closely for Semple's characteristic zingers. "It'll look funny if I'm back late from lunch," Sue Ann says after committing a particularly heinous crime. "Y'see, I'm on the honor roll."

Price, Vincent. Thriller, 1911-1993. Although he was known offscreen as a sophisticated gentleman who collected fine art, Price will forever be linked with the ghouls and goblins of the horror genre. His brooding quality, dramatic features, and melodic voice made him perfect for roles with a macabre bent, like the rich landowner with gruesome preoccupations in “Dragonwyck” (1946). Spooky cinema really took hold of Price’s career after the success of “House of Wax” (1953), an enjoyably operatic story featuring Price as a sculptor driven mad when his waxworks are destroyed in a fire. A tremendous amount of work in TV and features followed, with cheaply produced horror emerging as Price’s mainstay by the end of the ’50s; notable titles from this period include the William Castle-produced cult fave “The House on Haunted Hill” (1959), featuring Price in his signature guise as a crazed mastermind gleefully tormenting victims. During the early ’60s, Price’s skill for delivering atmospheric dramatic readings elevated the Edgar Allen Poe-inspired movies he made with producer-director Roger Corman; creepshows including “The Tomb of Ligeia” (1964) feature Price as men driven to violence by anguish. And while he won new fans with his wonderfully ridiculous turn as chrome-domed punster Egghead in the campy TV series “Batman” (1966-1968), among other comical roles, Price also gave deadly serious performances in ambitious fright flicks during this period. Price’s terrifying work as a sadistic zealot in “Witchfinder General” (1968) is of special note. (The actor memorably blended his silly and sinister sides in the arch horror-comedy hybrids “The Abominable Dr. Phibes” and “Dr. Phibes Rises Again,” released, respectively, in 1971 and 1972.) Price probably drifted too far into lampoonery with his appearances in a famous two-part 1972 episode of “The Brady Bunch,” and most of his career past that point comprises embarrassing roles in low-rent junk. Yet in the last decade of Price’s epic run, famous fans introduced him to new audiences. In 1983, Price delivered the narration of Michael Jackson’s megahit single (and video) “Thriller,” and in 1990, admirer Tim Burton cast Price for a touching featured role in “Edward Scissorhands.” Toward the end of his life, Price even got a few last chances to play non-horror roles, as with his endearing performance as a courtly Maine resident in “The Whales of August” (1987).

"The Prize Winner of Defiance, Ohio" (2005). A lively memory piece that packs an unexpected gender-politics punch, this true-life tale of a '50s Midwestern housewife who supports her family by winning jingle contests resonates with writer-director Jane Anderson' signature intelligence and purpose. Star Julianne Moore strikes one resonant chord after another playing Evelyn Ryan, a perpetually upbeat wit unfortunately tethered to the drunken, moody father of her 10 kids. Adapted from a memoir by one of those children, the picture sharply depicts the tension between Evelyn, whose literary talent gets the family out of one financial jam after another, and her husband Kelly (Woody Harrelson), who feels emasculated by her success. The tartest flavor in Anderson's movie is the pragmatic attitude Evelyn has toward her marriage: "I don't need you to make me happy," she tells Kelly at one point, "I just need you to leave me alone when I am." The director tricks up the piece with elements including animated bits and dialogue spoken directly to the camera, which keeps the vibe unpredictable and the pace quick. Yet it's the politics of the piece that resound, because Evelyn represents a generation of housewives suppressed by the vanity of their spouses and the Neanderthal mores of a patriarchal society.

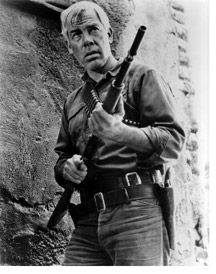

"The Professionals" (1966). One of those great lusty-men adventures with a cast full of, well, lusty men, this Western caper puts a crew led by Lee Marvin and Burt Lancaster to the task of rescuing va-va-voom Claudia Cardinale from creepy bandito Jack Palance. If you need to know more than that, the movie's probably not for you, but if you're already hooked, dive in. Director Richard Brooks moves things along at a confident pace, never rushing but still able to generate excitement when guns and dynamite start blasting, and the mugging of the stars is every bit as enjoyable as you might expect. Marvin plays the stoic leader, much as he did in the following year's "The Dirty Dozen," and Lancaster plays to the cheap seats as his explosives expert. What really distinguishes the picture is the resourceful story, adapted by Brooks from a novel by Frank O'Rourke. Beyond simply giving our antiheroes plausible motivations, the narrative provides a clever mid-story monkey wrench that politicizes the marauding mercs of the title. It doesn't hurt that cinematographer Conrad L. Hall fills every frame with rich color and that composer Maurice Jarre pulls the thing together with a rousing score.

"The Professionals" (1966). One of those great lusty-men adventures with a cast full of, well, lusty men, this Western caper puts a crew led by Lee Marvin and Burt Lancaster to the task of rescuing va-va-voom Claudia Cardinale from creepy bandito Jack Palance. If you need to know more than that, the movie's probably not for you, but if you're already hooked, dive in. Director Richard Brooks moves things along at a confident pace, never rushing but still able to generate excitement when guns and dynamite start blasting, and the mugging of the stars is every bit as enjoyable as you might expect. Marvin plays the stoic leader, much as he did in the following year's "The Dirty Dozen," and Lancaster plays to the cheap seats as his explosives expert. What really distinguishes the picture is the resourceful story, adapted by Brooks from a novel by Frank O'Rourke. Beyond simply giving our antiheroes plausible motivations, the narrative provides a clever mid-story monkey wrench that politicizes the marauding mercs of the title. It doesn't hurt that cinematographer Conrad L. Hall fills every frame with rich color and that composer Maurice Jarre pulls the thing together with a rousing score.

“The Purple Rose of Cairo” (1985). In the midst of the Depression, Cecelia (Mia Farrow) is burdened by economic hardship, a loveless marriage, a thankless job, and a tendency to daydream herself into trouble. Her greatest solace comes from the movies, especially the romantic adventure “The Purple Rose of Cairo,” featuring hunky explorer Tom Baxter (Jeff Daniels). And then one day, during her umpteenth viewing of the movie, Tom steps out of the screen to find out why she’s so infatuated. She returns the favor by showing her two-dimensional dreamboat around New York, much to the chagrin of his costars, who are still trapped in the movie. Gil Shepard (Daniels again), the actor who plays Baxter, isn’t too happy about the situation either. These are just the broad strokes of Woody Allen’s enchanting comedy, which is as poignant as it is whimsical. Though Daniels excels in dual roles as a hero and a heel, it’s Farrow’s quietly heart-wrenching portrayal that makes the piece more than a lark. An Allen film for those who don’t cotton to his neurotic excesses (and not just because he doesn’t appear in the movie), “Purple Rose” is arguably the best example of his storytelling acumen.

“Quick Change” (1990). Absurd, beautifully paced, and loaded with more top-notch acting firepower than is usually unleashed on farces, the sole movie to bear a Bill Murray directing credit is arguably the funnyman’s most underrated outing. (Howard Franklin wrote the screenplay and co-directed with Murray.) As Grimm, a disgruntled New Yorker turned exasperated bank robber, Murray finds a perfect vessel for his wiseass observations about city life and human foibles. Disguised as a clown (perhaps a knowing nod to Murray’s love-hate relationship with his chosen profession), Grimm cleverly absconds with cash—but then can’t get the hell out of New York. Evolving into a symphony of misunderstandings, close calls, and urban weirdness, Grimm’s abortive escape touches on a hundred reasons why the Big Apple is as maddening as it is magical. Geena Davis and Randy Quaid kill as Murray’s cohorts, with Jason Robards playing it straight as their frustrated pursuer, but what elevates the movie to comic bliss are the small roles played to perfection by Philip Bosco, Phil Hartman, Tony Shalhoub, Kurtwood Smith, and Stanley Tucci.

"Rabbit-Proof Fence" (2002). Australian filmmaker Philip Noyce took a bold step away from his signature big-budget action flicks with two strong films in 2002. While "The Quiet American" is a political thriller with a sophisticated sense of history, "Rabbit-Proof Fence" is a touching drama about an extraordinary historical incident. In the 1930s, Australia was divided physically and spiritually—a 1,500-mile fence designed to curtail rabbits cut through the land, and an insidious government policy of turning Aboriginal women into slaves cleaved the population. When young Molly Craig and two relatives fled a camp in which they were being trained as domestics, they defied a racist government and braved the unforgiving outback to follow the fence back home. Clearly enjoying the lack of a Hollywood agenda and the opportunity to film his homeland, Noyce makes Craig's adventure thrilling and inspiring, all while offering an unvarnished message about intolerance. Though Kenneth Branagh seethes entertainingly as the film's antagonist, the naturalistic acting of the Aboriginal performers gives the film its lush texture.

“Rachel Getting Married” (2008). Rightly celebrated for Anne Hathaway’s fearless lead performance, this raw dramedy also happens to be Jonathan Demme’s most accomplished narrative film since the consecutive triumphs of “Silence of the Lambs” (1991) and “Philadelphia” (1993). Sharing with those pictures an incisive focus on damaged characters but operating without the safety net of genre expectations, “Rachel” depicts a nightmare weekend in which a young woman leaves rehab, nearly derails her sister’s wedding celebration, and confronts the family tragedy that she caused during the nadir of her drug use. Two things separate this picture from the pack of similar stories. First, Demme’s deep interest in artists and bohemians makes even the smallest characters pop as unique individuals. Second, first-time scribe Jenny Lumet pulls off the rare trick of balancing lighthearted interplay with genuine pathos. The simple story structure, which follows the events of the wedding in chronological order, allows Demme and Lumet to jump from emotion to emotion, at one moment using human frailty as a window into the deepest parts of characters’ souls, and at the next using that same quality as a springboard for masterful dark comedy. It all hangs together surprisingly well, and Demme’s discipline only falters during an indulgent concert sequence featuring a few too many of the director’s musical pals. But given how vibrant and credible the storytelling is from start to finish, and given that the performances by Rosemarie DeWitt, Hathaway, Bill Irwin, and Debra Winger create an incandescent group portrait of a wounded nuclear family, Demme’s minor misstep doesn’t diminish the film’s vibrant energy.

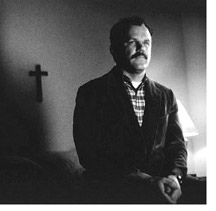

"The Rapture" (1991). An audacious drama that takes its intense subject matter to surprising extremes, Michael Tolkin's directorial debut follows a spiritually adrift woman's unexpected conversion to Christianity, then presents the character with an unimaginable dilemma that tests how deeply she's been changed by her newfound faith. Sharon (Mimi Rogers) is introduced as a nihilstic libertine drifting from one meaningless sexual encounter to another, but a chance encounter with devout Christians convinces her the endtimes are near. She starts a family and prepares for salvation, only to have fate intervene in cruel ways that rattle her confidence in God’s benevolence. Rogers gives her career-best performance, summoning great depths of anguish as her character moves from sexual abandon to religious calm to paralyzing ennui. Cinematographer Bojan Bazelli bathes the film in amber light that plays dramatically against the shadows with which Tolkin fills many of his frames, and the means by which the budget-challenged production achieves its key visual effects are highly resourceful, even when Tolkin succumbs to earnest talkiness. Also worth noting are solid supporting turns from Patrick Bauchau, David Duchovny, and Will Patton.

“Recount” (2008). A strong exercise in political docudrama helmed by comedy vet Jay Roach, who assumed directing duties when health issues forced Sydney Pollack to step aside, "Recount" plays like a Paddy Chayefsky satire even though it’s based on real events. Kevin Spacey plays Ron Klain, a chief operative in Vice President Al Gore’s efforts to claim victory in the 2000 presidential election. The filmmakers spin the facts a bit to present Klain as the sole entity protecting the truth (and the Constitution) in a political world gone mad, but the audience’s knowledge of what happened after the hanging chads makes the character’s crusade seem reasonable. Methodically examining every insane twist and turn of this historically disastrous episode, the filmmakers portray Democratic operatives as characteristically unwilling to go for the jugular, while demonizing Republican agents as ruthless masters of the political game. Every member of the ensemble cast connects in a different way (especially Laura Dern with her gleefully deranged take on Bush crony Katherine Harris), but it’s the quiet heartbreak that Spacey injects into his portrayal that grounds the piece.

“Red-Headed Stranger” (1986). More than a few movies in this guide are oddities that can’t withstand genuine critical scrutiny, but nonetheless offer rewards for those who enjoy particular flavors. In the case of this otherwise unremarkable Western, the flavor in question is Willie Nelson’s appealingly casual screen presence. Adapting his acclaimed concept album into a lean narrative, producer-star Nelson plays a rough-hewn preacher who drifts into a tiny frontier town with his pampered wife in tow. When the rigors of a rugged lifestyle drive her into the arms of a lover, the preacher becomes an avenging angel ready and willing to confront the corrupt forces demonizing his adopted hometown. It’s all very tragic and primal, digging into the themes of revenge and violence that often permeate Clint Eastwood’s Westerns. However producer-writer-director William D. Witliff, while skilled and deeply versed in the genre, lacks Eastwood’s poetry, so the execution falls flat on a number of fronts. The camerawork is utilitarian, the cast is filled with talented but generic character players, and leading lady Morgan Fairchild seems anachronistic as Nelson’s wife. (Katharine Ross, as Nelson’s other love interest, suits the piece much better.) Still, the power of Nelson’s lurid story and the charm of his lived-in performance compensate for the film’s shortcomings.

"The Red Violin" aka "Le Violin rouge" (1998). Weaving together several disparate timelines by tracking the colorful travels of a special musical instrument, Francois Girard's captivating movie explores art, love, obsession, jealousy, grief, and passion, among myriad other sensations. Samuel L. Jackson anchors the piece as a collector trying to validate whether the instrument he's found is the legendary "red violin," and cowriters Girard and Don McKellar leap from Jackon's investigation to literary vignettes about the instrument's previous owners. The vignettes are full-blooded mini-movies that traverse Europe, Asia, and North America while gracefully revealing the wildly romantic secret of the prized violin. A deft high-wire act that never once loses its footing or its momentum, the picture benefits from a slew of impassioned performances, sensual photography, and, fitting its subject matter, elegant scoring (by John Corigliano).

Reed, Oliver. Dipsomaniac, 1938-1999. Given his legendary thirst for hard drink, it's remarkable that Reed lived long enough to film most of his last role, as Russell Crowe's burly mentor in "Gladiator" (2000). From the late '50s onward, Reed cut a brazen swath through world cinema, picking roles indiscriminately to accommodate his offscreen excesses. Thickly built, darkly handsome, and smolderingly charismatic, Reed might easily have become a dangerous leading man at any of several points in his career had the right opportunities materialized and had his artistic ambitions eclipsed his affection for the pub life. Even some of his best performances seem erratic, with Reed poetically virile one moment and monotonously flaccid the next. Yet his spotty output includes many extraordinary moments, in movies of both great and very little artistic merit. On the less challenging side, there's genre stuff including 1961's "The Curse of the Werewolf," a Hammer outing steeped in tragic romanticism. On the artier side, there's 1969's "Women in Love," the peculiar Ken Russell drama featuring a nude wrestling match between Reed and Alan Bates. To my taste, Reed's quintessential performance was in "The Three Musketeers" (1973) and "The Four Musketeers" (1975). The actor's interpretation of swordsman Athos is haunted, lusty, frightening, and heroic—I like to think the characterization expressed something primal about Reed's blazing soul. Other notable appearances include those in the Oscar-winning musical "Oliver!" (1968), helmed by the actor's uncle Carol Reed, and "Gladiator." For the latter film, director Ridley Scott employed costly CGI effects to complete Reed's performance as a tribute to the actor, who died from a heart attack during production.

Reilly, John C. Actor, b. 1965. With a palooka's bulky build and sad-sack face, Reilly got into a rut of routine supporting parts during his first few years of movie work. Then came writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson, who tapped into the actor's reservoir of soulfulness for "Hard Eight" (1996), featuring Reilly as a hapless gambler; "Boogie Nights" (1997), with the actor as a doofus porn star; and "Magnolia" (1999), in which Reilly plays a dim-bulb cop infatuated with a junkie. In each of Anderson's pictures, Reilly displays a unique gift for imbuing unlucky mugs with dignity. By the time he finished his third Anderson picture, Reilly was established as a top character player, and he quickly proved himself full of surprises. In the 2002 musical "Chicago," Reilly gave the movie's most affecting performance as everyman Amos Hart—his solo number, "Mr. Cellophane," seemed to double as a lament for the way Reilly blends into the fabric of movies, no matter how dynamic his roles. For better or worse, Reilly’s profile finally started to rise with his appearances in a string of silly comedies: “Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby” (2006), “Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story” (2007), “Step Brothers” (2008), and so on. Luckily, work in more substantive pieces, such as the insightful indie "Cyrus" (2010) and the amiable Western "The Sisters Brothers" (2018), balances Reilly's appearances in frothy flicks.

Reilly, John C. Actor, b. 1965. With a palooka's bulky build and sad-sack face, Reilly got into a rut of routine supporting parts during his first few years of movie work. Then came writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson, who tapped into the actor's reservoir of soulfulness for "Hard Eight" (1996), featuring Reilly as a hapless gambler; "Boogie Nights" (1997), with the actor as a doofus porn star; and "Magnolia" (1999), in which Reilly plays a dim-bulb cop infatuated with a junkie. In each of Anderson's pictures, Reilly displays a unique gift for imbuing unlucky mugs with dignity. By the time he finished his third Anderson picture, Reilly was established as a top character player, and he quickly proved himself full of surprises. In the 2002 musical "Chicago," Reilly gave the movie's most affecting performance as everyman Amos Hart—his solo number, "Mr. Cellophane," seemed to double as a lament for the way Reilly blends into the fabric of movies, no matter how dynamic his roles. For better or worse, Reilly’s profile finally started to rise with his appearances in a string of silly comedies: “Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby” (2006), “Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story” (2007), “Step Brothers” (2008), and so on. Luckily, work in more substantive pieces, such as the insightful indie "Cyrus" (2010) and the amiable Western "The Sisters Brothers" (2018), balances Reilly's appearances in frothy flicks.

"Resurrection" (1980). Strange, gripping, and frequently poetic, Daniel Petrie's drama follows the unexpected path of a woman pulled back from death by modern medicine. Ellen Burstyn, in one of her most expansive roles, occupies a range of vivid emotional states as Edna, the auto-accident victim who's as shocked as anyone to discover that her afterlife experience granted her magical healing powers. While Lewis John Carlino's script of course ventures into the fantastic, Petrie, Burstyn, and the strong cast keep even the most outlandish moments grounded in recognizable interpersonal dynamics. Sam Shepard is fierce as Edna's paramour, who can't get past Edna's reluctance to put her experiences in a religious context, and Richard Farnsworth contributes his signature countrified amiability to a key role. Though unique on many levels, perhaps the most idiosyncratic element of "Resurrection" is its ending, which eschews the standard frantic Hollywood climax for a provocative coda that takes Edna's journey to an organic conclusion.

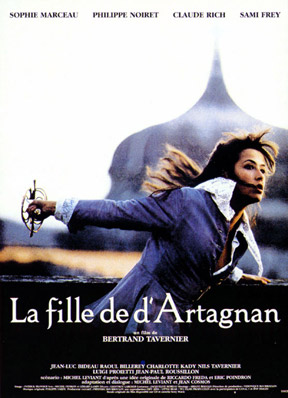

"Revenge of the Musketeers" aka "La Fille de D'Artagnan" (1994). Somewhat in the spirit of Richard Lester's lighthearted swashbucklers, albeit with more danger and less physical comedy, this enjoyable romp finds an aging D'Artagnan and his comrades summoned to action when D'Artagnan's spirited daughter, Eloise (Sophie Marceau), discovers a political conspiracy in 17th-century France. (The movie's story is predicated on the usual palace-intrigue business about a scheme to unseat a king, in this case Louis XIV, though the narrative mechanics of swashbuckler pictures are always secondary to, well, the buckling of swashes.) Marceau, best known to American audiences for her role in "Braveheart" (1995), is suitably feisty and formidable in the lead role, even doing her own onscreen fencing. She's also dazzlingly beautiful, a fact accentuated perhaps too enthusastically by the film's leering topless shots. Veteran French actor Philippe Noiret brings an endearing quality to the familiar D'Artagnan character, portraying him as a man trying to reconcile the passage of time with the desire for adventure, so there’s real joy once he and his aging friends join Eloise in fighting the good fight. Though Bertrand Tavernier's movie is far from perfect—no surprise, given that Tavernier took over as director once production was underway—energetic performances, lush production values, and vivacious fight scenes compensate for such shortcomings as turgid plotting and a bloated running time.

"Revenge of the Musketeers" aka "La Fille de D'Artagnan" (1994). Somewhat in the spirit of Richard Lester's lighthearted swashbucklers, albeit with more danger and less physical comedy, this enjoyable romp finds an aging D'Artagnan and his comrades summoned to action when D'Artagnan's spirited daughter, Eloise (Sophie Marceau), discovers a political conspiracy in 17th-century France. (The movie's story is predicated on the usual palace-intrigue business about a scheme to unseat a king, in this case Louis XIV, though the narrative mechanics of swashbuckler pictures are always secondary to, well, the buckling of swashes.) Marceau, best known to American audiences for her role in "Braveheart" (1995), is suitably feisty and formidable in the lead role, even doing her own onscreen fencing. She's also dazzlingly beautiful, a fact accentuated perhaps too enthusastically by the film's leering topless shots. Veteran French actor Philippe Noiret brings an endearing quality to the familiar D'Artagnan character, portraying him as a man trying to reconcile the passage of time with the desire for adventure, so there’s real joy once he and his aging friends join Eloise in fighting the good fight. Though Bertrand Tavernier's movie is far from perfect—no surprise, given that Tavernier took over as director once production was underway—energetic performances, lush production values, and vivacious fight scenes compensate for such shortcomings as turgid plotting and a bloated running time.

Reynolds, Burt. Hirsute icon, 1936-2018. The man with the moustache was at the top of his game around the time I started going to the movies, so perhaps that's why he's still my paradigm of a movie star. Or perhaps it's because of the way Reynolds' joie de vivre permeated his performances and his ruthlessly charming TV appearances, which usually involved berating Dom DeLuise while making Dinah or Johnny or Merv convulse with laughter. Whatever the case, now that his story is over (no more of that elder-statesman bunk, with rare juicy roles offering reprieves from crap projects and wink-wink commercials), it's interesting to look back at how badly Reynolds squandered his glory years. Aside from a handful of good pictures, notably "Deliverance" (1972), "The Longest Yard" (1974), "Semi-Tough" (1977), and "Starting Over" (1978), most of what Reynolds made during his run atop the box office was awful. And that was just a prelude for the cinematic misery of the Loni years, with all due respect to the health problems Reynolds suffered at the time. Still, even in sludge like the "Smokey and the Bandit" pictures or, God forbid, the "Cannonball Run" movies, Reynolds had such a good time being a movie star that his presence almost made execrable movies entertaining. Darker performances, as in his interesting directorial efforts "The End" (1978) and "Sharky's Machine" (1981), hinted at depth he never fully exploited onscreen, and of course he did some of his best work in later life. He was a hoot and a half as a deranged politico in "Striptease" (1996), and there's real gravitas to his turn as a porn king in "Boogie Nights" (1997). Though cosmetic surgery and widely publicized financial reversals took the option of aging gracefully off the table, Reynolds built a cinematic legacy of which any actor could be proud. Case in point: "Hooper" (1978). While hardly an unsung gem, the distracting trifle about an aging stunt man is a perfect snapshot of wiseass Burt at the height of his powers. He's macho, funny, cranky . . . and he looks like he couldn't care less about the movie. In his last years, Reynolds completed a few noteworthy victory laps. He published a second (!) autobiography in 2015, and two years after that, cult-fave filmmaker Adam Rifkin showcased Reynolds as a faded screen icon in the warmhearted indie "The Last Movie Star."

Rhames, Ving. Actor, b. 1959. Though he'd already been in movies for a decade, it wasn't until Rhames announced his intentions to "get medieval" on a rapist in "Pulp Fiction" (1994) that he won stardom. As the eloquently brutal gangster Marcellus Wallace, Rhames was able to make as much of an impression with his precise vocal delivery as he was with his startling look. In the late '90s, Rhames began his run of leading roles in a variety of genres, sometimes playing up his massive build and sometimes diving into pure character work. In 1997's "Rosewood," he's an Eastwood-type mystery man who tries to save a black town from extermination by racist whites; in 2001's "Baby Boy," he's a reformed gang-banger; and in 2001's "Dark Blue," he's a morally conflicted police chief surrounded by racism and corruption. The actor also enjoys a steady gig as one of Tom Cruise's sidekicks in the "Mission: Impossible" movies, and he's warmly funny in comedies such as "Striptease" (1996). Rhames also created a truly great television moment in 1998, when he won a Golden Globe for playing the titular boxing promoter of "Don King: Only in America." Noting the achievements of fellow nominee Jack Lemmon, Rhames gave his award to the elder actor.

Rhodes, Hari. Actor, 1932-1992. Handsome and charismatic, Cincinnati native Rhodes enjoyed a steady television career from the early '60s to the mid-'80s, appearing as a regular on the adventure series "Daktari" (1966-1969), a costar of the short-lived crime show "The Bold Ones: The Protectors" (1969-1970), and a featured actor in the legendary minseries "Roots" (1977), among myriad other credits. His feature career was less successful, as evidenced by the fact that he only recieved star billing once, for the dull blaxploitation flick "Detroit 9000" (1973), though he was prominently featured a decade earlier amid the ensemble cast of Samuel Fuller's pulpy drama "Shock Corridor" (1963). A military veteran who also wrote novels, Rhodes never landed a signature role, so it's interesting (and a bit depressing) to survey his film performances and imagine what sort of star he might have become had he been given more substantial opportunities. In "Conquest of the Planet of the Apes" (1972), Rhodes is authoritative and impassioned as a voice of reason amid chaos, and in the brisk opening sequence of "Sharky's Machine" (1981), the actor's last theatrical feature, he amusingly berates a white cop for adopting African-American patois.

Rickman, Alan. Poet of pith, 1946-2016. Rickman’s star turn as suave villain Hans Gruber in “Die Hard” (1988) is one of the great performances of the modern blockbuster era, because Rickman conveyed a character as erudite as he was odious. After cementing his international notoriety with another bad-guy turn in “Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves” (1991)—which features Rickman gloriously instructing his underlings to “Call off Christmas!”—he began alternating showy roles in big features and subtler turns in more intimate movies. And though he was quite affecting when playing it straight, striking tiny emotional notes that speak volumes about enigmatic characters, Rickman was invaluable when unleashed. He’s screamingly funny as a world-weary angel in “Dogma” and as an embittered TV has-been in “Galaxy Quest” (both 1999), two of the most endearingly bitchy characters ever presented on film. The lilting rhythms with which he spoke and the elegance with which he carried himself also made him a plaintive romantic figure, in such varied films as the supernatural romance “Truly Madly Deeply” (1991), the lush literary adaptation “Sense and Sensibility” (1995), and the ensemble rom-com “Love Actually” (2003). As evidenced by the impact Rickman made with recurring appearances in the Harry Potter movies, featuring the London native in ghoulish drag as mysterious instructor Severus Snape, he was an actor of immeasurable skill and versatility.

“The Right Stuff” (1983). Adapted from Tom Wolfe’s popular nonfiction book about the development of America’s space program, Phillip Kaufman’s epic movie is almost unclassifiable, because while it’s ostensibly a drama, it’s also a thrilling action picture and, at moments, a laugh-out-loud comedy. Beginning with the groundbreaking daredevil flights of Chuck Yeager (Sam Shepard) circa 1947, a time when trying to break the sound barrier was a life-threatening endeavor, the picture continues through to the early '60s, by which point a series of successful orbiting missions had opened the door to fully crewed spaceflights instead of daring solo jaunts. Along the way, viewers are introduced to a variety of colorful personalities, from square-jawed conservative John Glenn (Ed Harris) to wild men like Gordy Cooper (Dennis Quaid) and Gus Grissom (Fred Ward). Watching these would-be heroes duke it out for the glory of being the first American to achieve such-and-such feat is wonderfully exciting, especially since there’s a constant background noise of genuine danger. Kaufman’s brilliant script sketches the fierce political battles waged around the space program, touching on everything from America’s celebrated “space race” with Russia to the bittersweet fact that Yeager never actually became an astronaut. “The Right Stuff” is not for every taste, given its wild tonal shifts, but for those willing to indulge Kaufman’s whimsy, the movie is filled with interesting things, not least of which are flawless special effects and powerhouse acting from an eclectic ensemble.

"Risky Business" (1983). Incidentally the launching pad for Tom Cruise's stardom, Paul Brickman's debut movie is one of the essential movies from an iffy cinematic decade. Funny, sexy, stylish, and right on target in its skewering of capitalistic ambition, the comedy concerns an undersexed high schooler (Cruise) who unexpectedly turns his suburban home into a brothel. Watching the sheltered protagonist learn life lessons from people in the sex trade reveals profound truths about the gulf between those born to privilege and those who scrape for every penny. Comedy highlights include a memorable interview with a college recruiter and various run-ins with “Guido the Killer Pimp,” while the sex scenes radiate real heat. Loaded with tart supporting performances (by Curtis Armstrong, Rebecca DeMornay, Richard Masur, Joe Pantaliano, and others), the picture also boasts a hypnotic score by synth specialists Tangerine Dream, albeit one so influenced by the work of avant-garde composer Steve Reich that he sought legal recourse. And, yes, even if you've seen that clip of Cruise dancing to "Old Time Rock and Roll" too often, "Risky Business" is still a pleasure to watch because it has an almost perfect script, and because it unfurls with pacing as remarkably assured as Brickman’s sense of sociocultural purpose.

"RKO 281" (1999). Dissected repeatedly in books, memoirs, articles, and at least one acclaimed documentary, the tumultuous story behind the making of "Citizen Kane" (1941) remains one of the most entertaining chapters of Hollywood history, so it's no surprise that this telefilm about Orson Welles' debut movie is so engrossing. All of the infamous anecdotes are here, from Welles chopping open a studio floor so he can shoot an extreme low-angle shot to William Randolph Hearst, the real-life model for Charles Foster Kane, conspiring to destroy every print of Welles' picture. Director Benjamin Ross, screenwriter John Logan, and their collaborators defy the story's episodic nature by interlacing several key threads, most importantly the stormy relationship between Welles and his sodden cowriter Herman Mankiewicz. Though Liev Shreiber gamely tackles the impossible task of playing Welles, Malkovich handily steals the movie as embittered, brilliant Mankiewicz; the actor gives one of his most restrained, effective turns as a tragic figure overwhelmed by the prospect of artistic redemption. Other standouts include Roy Scheider, amusingly exasperated as RKO boss George Shaefer, and Brenda Blethyn, gleefully bitchy as gossip queen Louella Parsons. Though undoubtedly vulnerable to nitpicking from those familiar with the historical details portrayed onscreen, "RKO 281" is a great introduction to the "Kane" backstory, and also a smart look at the many faces of hubris.

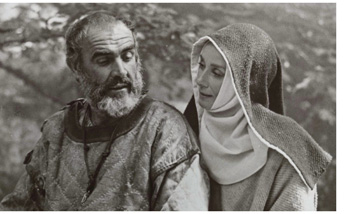

"Robin and Marian" (1976). Deeply moving for those who buy into its premise, this gorgeous love story finds Robin Hood (Sean Connery) and Maid Marian (Audrey Hepburn) living apart in their twilight years. An adventure involving all their old compatriots and enemies draws them back together, with surprising results. Telling a grown-up fable as concerned with aging and love as it is with myth and derring-do, writer James Goldman blends poignancy, humor, and a touch of spectacle. And who better than Richard Lester, the maestro of the great '70s Musketeer movies, to conduct this bittersweet symphony? Capturing moments with his sly multicamera style, which gives even the most rehearsed scenes a haphazard feel, Lester benefits from a spectacular cast. Richard Harris plays a dottering Richard the Lionheart, Nicol Williamson and Denholm Elliot elegantly portray Robin's merriest men, and Robert Shaw makes a majestically evil Sheriff of Nottingham. Yet even with all this talent around them, Connery and Hepburn—an unexpected but inspired screen pairing—paint a beautiful picture all their own.

"Robin and Marian" (1976). Deeply moving for those who buy into its premise, this gorgeous love story finds Robin Hood (Sean Connery) and Maid Marian (Audrey Hepburn) living apart in their twilight years. An adventure involving all their old compatriots and enemies draws them back together, with surprising results. Telling a grown-up fable as concerned with aging and love as it is with myth and derring-do, writer James Goldman blends poignancy, humor, and a touch of spectacle. And who better than Richard Lester, the maestro of the great '70s Musketeer movies, to conduct this bittersweet symphony? Capturing moments with his sly multicamera style, which gives even the most rehearsed scenes a haphazard feel, Lester benefits from a spectacular cast. Richard Harris plays a dottering Richard the Lionheart, Nicol Williamson and Denholm Elliot elegantly portray Robin's merriest men, and Robert Shaw makes a majestically evil Sheriff of Nottingham. Yet even with all this talent around them, Connery and Hepburn—an unexpected but inspired screen pairing—paint a beautiful picture all their own.

Rocco, Alex. Actor, 1936-2015. Though he will forever be known as Moe Green, the mobster who takes a bullet through the eye in “The Godfather” (1972), Rocco was the quintessential Hollywood utility player. A dark-featured Bostonian who entered the business playing thugs and bikers, he got typecast as a gunsel following his ocular assault, then spent the better part of the ’70s playing guys named Ernie, Frank, Tony, and the like in countless TV shows and minor features. Notwithstanding sly turns like his frenetic performance as an exasperated district attorney in the ahead-of-its-time actioner “Freebie and the Bean” (1974), Rocco’s recurring role as a blue-collar dad on the mushy ’80s sitcom “The Facts of Life” foreshadowed the second act of the actor’s career, when he dove headlong into broad comedy. A riotous performance as unscrupulous agent Al Floss on the short-lived sitcom “The Famous Teddy Z” (1989-1990) landed Rocco an Emmy and even a guest shot as the same character on “Murphy Brown.” In his later years, Rocco balanced the extremes of his screen persona, alternating between comedy gigs and dramatic turns such as his recurring role on the Lifetime series “The Division” (2001-2004).

“The Royal Hunt of the Sun” (1969). Before taking on twisted sexuality in “Equus” and artistic envy in “Amadeus,” playwright Peter Shaffer tackled the epic adventures of Spanish conqueror Francisco Pizarro, and powerhouse actors participated in the play’s fascinating film adaptation. Robert Shaw, scowling and growling as only he can, tears into the role of Pizarro, a megalomaniac obsessed with finding a legendary city of gold. When his quest leads him to Peru, Pizarro encounters the Incan ruler Atahuallpa, who believes himself the divine child of the sun. Pizarro's armada slaughters Atahuallpa’s royal guard, takes the king prisoner, and demands ransom in gold. Pizarro engages in long dialogues with his exotic prisoner, discovering a kindred spirit: Both are illegitimate, illiterate, and intoxicated by power. All of this material is quite provocative, and Shaffer’s dialogue is transporting in a faux-classical kind of way, but the X factor is Christopher Plummer’s performance as Atahuallpa. He adopts a peculiar accent that evokes the Pacific Rim more than it does South America, then punctuates scenes with strange childlike noises. The portrayal is so unique it borders on the absurd. Still, the power of Shaffer’s writing shines through as gigantic themes of divinity, faith, greed, and honor are explored. The movie benefits from minimalistic production values that keep the focus on words, and Mark Wilkinson’s resourceful score blends majestic European horns with hypnotic ethnic rhythms.

"Rumble Fish" (1983). For a brief moment in the '80s, it seemed all Matt Dillon did was play tortured teens in adaptations of S.E. Hinton novels. "Tex" (1982) put him on the map, "The Outsiders" (1983) placed him amid an ensemble of future stars, and "Rumble Fish" closed the cycle in high style. Directed seemingly in the same breath as "The Outsiders" by Francis Ford Coppola, "Rumble Fish" is one of Coppola's most visually audacious movies, and given the dazzlers on his filmography, that's saying quite a bit. Filmed in luminescent black-and-white by Stephen H. Burum, with arty flashes of color here and there, the surrealistic film explores how Rusty (Dillon) tries to live in and out of the shadow of his gang-leader brother, Motorcyle Boy (Mickey Rourke). Fights, love scenes, cycle rides, and even transitional moments are shot with assertive angles right out of German Expressionism, and Stewart Copeland, drummer of the rock band the Police, contributes a jittery score that amplifies the weirdness. The supporting cast features an exciting mix of fresh-faced youth and grizzled middle age, with Nicolas Cage, Laurence Fishburne, Dennis Hopper, Diane Lane, Chris Penn, and Tom Waits among the players.

"Running on Empty" (1988). Springing imaginatively from the dilemma of what might happen to '60s radicals who committed themselves to social change but never quite envisioned where their lives would lead them, Sidney Lumet's sensitive drama captures a family in a unique crisis. The parents (Judd Hirsch and Christine Lahti) blew up a napalm lab to protest the Vietnam War, inadvertently killing someone and then going underground for nearly two decades to evade capture. But when they realize that their gifted son (River Phoenix) needs to attend a high-profile school to pursue his musical dreams, they face an awful choice—keep the family together, or stifle their son’s promise because of choices they made when they were his age. The setup is rich and thoughtful, illustrating how the family evades capture by relying on a network of diehard lefties, and the middle of the movie veers a bit toward the episodic. However, the last stretch of the picture is devastating, especially when Lahti's estranged father (Steven Hill) appears for one heartbreaking scene. Phoenix amply deserved his sole Oscar nomination, if only for the disarming sincerity he brings to the movie's climax.

A-C D-F G-I J-L M-O P-R S-U V-Z

home • news • books and movies • field guide • services • journalism • gallery • bio