peter hanson's field guide to interesting film

Daniels, Jeff. Actor, b. 1955. With his corn-fed look and six-foot-three frame, Daniels could have enjoyed a bland career playing stalwart dads and the occasional heel, but he followed a bolder path. He first caught notice in the early '80s, especially in Woody Allen's wondrous "The Purple Rose of Cairo" (1985). As both a heartthrob actor and his onscreen alter ego, Daniels simultaneously imbues and satirizes the square-jawed persona to which he seems most naturally suited. He floundered a bit after his first fame, casting about for leading roles that gave him room to display his considerable dexterity; in the early '90s, he tried playing everything from wan action heroes (in 1990's "Arachnophobia") to doofus comic foils (in 1994's "Dumb and Dumber"). He also found ways to vary the particulars of those unavoidable dad roles, as in 1996's "Fly Away Home"; his portrayal of a man not ideally suited for parenting has memorably weird colorations. An even rougher paternal characterization arrived ten years later in the scathing divorce drama "The Squid and the Whale," wherein Daniels' love interest is played by Anna Paquin, who portrayed his daughter in "Fly Away Home." Hopping into the cinematic sack with someone who's been your onscreen kid isn't the choice of an actor who plays it entirely safe, and that's Daniels: Virtuous as he may seem, there's something delightfully dangerous inside. Daniels essayed yet another dimensional dad with his celebrated 2018-2019 run as Atticus Finch in Aaron Sorkin's phenomenally successful Broadway adpatation of "To Kill a Mockingbird."

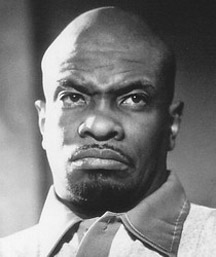

David, Keith. Actor, b. 1956. With his thundering voice, a stentorian instrument that wins him steady employment in cartoons and commercials, David is a powerful figure whether onscreen or not. Tall and graceful, he made his first indelible impression amid the manly ensemble of John Carpenter's "The Thing" in 1982. Six years later, he participated in Carpenter's jump-the-shark moment by brawling with "Rowdy" Roddy Piper for what seemed an eternity during "They Live." In both pictures, David was perfectly simpatico with Carpenter's comic-book style, offering oversized menace leavened with knowing humor. Jokes took the forefront in another of his most memorable appearances, as a concerned dad observing Ben Stiller's nightmare injury in "There's Something About Mary" (1998). David adds smooth danger to gritty cop roles, as in "Clockers" (1995) and "Dirty" (2005), and he's intense when given chewy dramatic roles, as in "Platoon" (1986), "Bird" (1988), and "Requiem for a Dream" (2000). Yet it's that voice, whether hawking products on TV ads, narrating documentaries, or enlivening animated characters, that remains David's calling card.

David, Keith. Actor, b. 1956. With his thundering voice, a stentorian instrument that wins him steady employment in cartoons and commercials, David is a powerful figure whether onscreen or not. Tall and graceful, he made his first indelible impression amid the manly ensemble of John Carpenter's "The Thing" in 1982. Six years later, he participated in Carpenter's jump-the-shark moment by brawling with "Rowdy" Roddy Piper for what seemed an eternity during "They Live." In both pictures, David was perfectly simpatico with Carpenter's comic-book style, offering oversized menace leavened with knowing humor. Jokes took the forefront in another of his most memorable appearances, as a concerned dad observing Ben Stiller's nightmare injury in "There's Something About Mary" (1998). David adds smooth danger to gritty cop roles, as in "Clockers" (1995) and "Dirty" (2005), and he's intense when given chewy dramatic roles, as in "Platoon" (1986), "Bird" (1988), and "Requiem for a Dream" (2000). Yet it's that voice, whether hawking products on TV ads, narrating documentaries, or enlivening animated characters, that remains David's calling card.

“The Day Reagan Was Shot" (2001). Lurid, tense, and even farcical, this juicy telefilm depicts the chaos that erupted among the president’s men after a wannabe assassin's bullet incapacitated the Gipper. Centered around Secretary of State Alexander Haig, who famously said he was "in control" of the government when neither fact nor the Constitution backed up his claim, writer-director Cyrus Nowraseth’s brisk docudrama patches together every notorious episode that followed the shooting. A startling picture emerges of a political cabal coming apart at the seams because of personal rivalries, unchecked ambition, conflicting agendas, and simmering Cold War tension. Given Oliver Stone's presence as executive producer, it's unsurprising that the movie paints unflattering portraits of Reagan (a detached leader preoccupied with appearances), Caspar Weinberger (an inexperienced Secretary of Defense who makes a dangerous blunder), and George H.W. Bush (a blindly loyal vice president). Reagan's core "troika" of advisors fares worst of all, coming off as duplicitous operators desperate to retain power, and Holland Taylor portrays Nancy Reagan almost too vividly as a powerhouse defender of her dear Ronnie. The most surprising interpretation is that of Haig, played with typical flair by Richard Dreyfuss. He's presented as an iron-willed military man so devoted to his country and so rigidly sure of his rectitude that he snaps when handed more authority than he can handle. Dreyfuss' performance is commanding and, as always, thoroughly entertaining.

“The Deadly Tower” (1975). One byproduct of the ’70s heyday of made-for-TV movies was that a number of lurid real-life stories received the low-budget docudrama treatment, often with slapdash results. But amid the sensationalistic tripe were a few strong pictures like “The Deadly Tower,” a meticulous dramatization of the infamous shooting spree that terrorized the University of Texas at Austin’s campus on August 4, 1966. That was the day clean-cut youth Charles Whitman (Kurt Russell) killed his mother and wife, then set up a sniper station atop the UT tower and opened fire on an unsuspecting citizenry, killing 13 people and wounding 34 more before police took him down. Slyly casting Russell, then best known for family-friendly appearances in Disney flicks, “The Deadly Tower” offers a clinical portrayal of the grisly events, summoning the horror of the day more effectively than would have been possible if the filmmakers elected to editorialize on the killer’s unknowable motivations. (As noted in the film’s postscript, an autopsy revealed a brain tumor, which only offers partial explanation.) Brisk and disquieting, the picture also features solid supporting work by Ned Beatty, John Forsythe, and Richard Yniguez.

“The Dead Zone” (1983). After sensitive everyman Johnny Smith (Christopher Walken) survives a horrific car accident and the ensuing coma, he gains the ability to glimpse the future. Simple enough, right? Not so much. Directed by David Cronenberg at his most incisive, “The Dead Zone” blends supernatural horror, doomsday politics, aching romance, and personal tragedy into 103 compelling minutes. Jeffrey Boam’s taut script blasts through key beats from Stephen King’s novel, snaring Johnny in a narrative net that leaves him no choice but to take irreversible action. The plot is so sly that it’s better discovered than discussed, but two of the key players are Sarah (Brooke Adams), the woman who didn’t wait while Johnny lingered in his coma; and Greg Stillson (Martin Sheen), a rising politician with a Cold War gleam in his eyes. Though the telepathy stuff gives Walken plenty of room to display his signature otherworldliness, he’s really most affecting in the human moments, because he plays a guy who desperately wants the one thing he can’t have: normalcy. In lieu of that, he’ll take heroism, but as the film provocatively dramatizes, valor is cold comfort for the loss of everyday pleasures.

“A Decade Under the Influence” (2003). An epic exploration of my personal favorite period in American cinema, this engrossing travelogue by fans/filmmakers Ted Demme and Richard LaGravenese simultaneously celebrates the artistry of counterculture talents who shook up Hollywood in the ’70s and records the excesses that ensured a swift conclusion to the era of the “New Hollywood.” Though not every major player from the period participated, the documentarians scored tasty commentary from Robert Altman, Julie Christie, Francis Ford Coppola, Roger Corman, William Friedkin, Sidney Lumet, Paul Mazursky, Martin Scorsese, and dozens of others, resulting in an almost-comprehensive overview. Funny highlights include Bruce Dern rolling out his trusty Jack Nicholson impression, and the various survivors of Corman’s low-budget film factory describing his shoot-first-ask-questions-later ethos. Yet “Decade” also hits important sociopolitical points, detailing how the counterculture filmmakers provided frank onscreen explorations of consciousness-raising, the drug culture, and gender relations, among a host of other topics. “Decade” is a bit of a lovefest, to be sure, and the interview subjects were probably thrown softball questions designed to trigger familiar cocktail-party stories, but how can any film fan resist hearing stories about Terrence Malick filming “Badlands” or Scorsese making “Mean Streets”? If “Decade” leaves you wanting more, read Peter Biskind’s definitive book on the subject, “Easy Riders, Raging Bulls,” and check out the feature-length doc version of Biskind’s book, which was released the same year as “Decade”; taken together, the three projects offer a fabulously entertaining crash course in an essential era.

“Deliverance” (1972). Yes, the whole “squeal like a pig” bit is enough to make grown men whimper, but it’s just the most outrageous incident in this consistently absorbing and actually quite weird thriller. Adapted by poet James Dickey from his novel, the stylized movie follows several mismatched buddies during a canoe trip that goes awry when they cross paths with psychotic hillbillies. Designed as a clinical study of 20th-century manhood, the movie explodes archetypes left and right. As reckless stud Lewis, Burt Reynolds personifies primitive man bashing against modern societal confines, so of course the movie finds a way to emasculate him. And as cerebral sensitive guy Ed, Jon Voight represents civilized man struggling to recover his killer instinct, so of course the movie puts him into one desperate situation after another. Poor Ned Beatty, the recipient of the “squeal like a pig” assault, stands for the everyman who straddles the extremes of the other characters. As helmed by British maverick John Boorman, the movie sways from brutal action scenes to strangely lyrical passages, introducing one disquieting ambiguity after another. Deeper and more elegant than any of the pulpy copycats that followed in its wake, “Deliverance” is as provocative and unsettling now as it was in 1972.

Dennehy, Brian. Actor/filmmaker, 1938-2020. Bearish, tall, and shrewd, Dennehy became one of my favorite performers when I first encountered him playing the small-town sheriff who unwisely antagonizes an ex-Green Beret in "First Blood" (1982). Though he had already been appearing in movies and television for several years by that point, notably drawing on his pigskin past for a supporting role in "Semi-Tough" (1977), Dennehy hit his stride in the early '80s. He played memorable antagonists in "Never Cry Wolf" (1983) and "Silverado" (1985), worked a more benevolent vibe as an alien in "Cocoon" (1985), and costarred in the cult-fave actioner "F/X" (1986). Working at a relentless pace during his breakthrough years, Dennehy played an impressive array of character types and appeared in just about every genre imaginable, so fans were as likely to find him playing comic roles on sitcoms as they were to encounter him playing Arthur Miller on Broadway. An actor of infallible instincts who made rote characters vivid and complex characters magnetic, Dennehy mostly confined his behind-the-camera endeavors to the small screen; he directed, produced, and/or cowrote a series of mid-'90s telefilms about a tough-guy cop named Jack Reed, whom he played in blustery fashion.

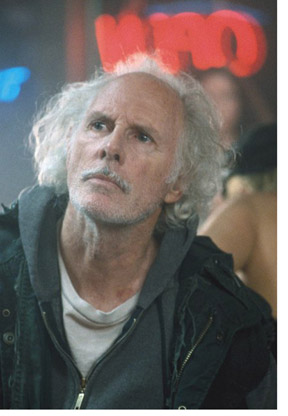

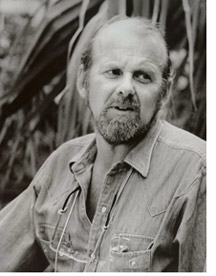

Dern, Bruce. Actor, b. 1936. After paying his dues as a rank-and-file studio player in the early '60s, Dern ventured to weirder places in such offbeat pictures as "Psych-Out" (1968), a hippie phantasmagoria in which he plays an addled messianic type called The Seeker, and "They Shoot Horses, Don't They" (1969), in which he and the other members of an eclectic cast spin themselves to exhaustion during a dance marathon. Tall and lean, often wearing the pinched expression of a ferret, Dern became a leading man at just the right time, granting his slow-burn intensity and spaced-out line readings to several unmistakably New Hollywood productions. It says a lot that in "The King of Marvin Gardens" (1972), Jack Nicholson plays straight man to Dern's maniac; one should never underestimate a performer who could outmug Nicholson in the early '70s. The major films in which Dern is the sole lead are few, and most of them are bizarre. "Silent Running" (1972) is an elegiac drama about the last trees in space, complete with a warbly Joan Baez theme song and a tearjerker ending; "Tattoo" (1981) features Dern as a wacko who kidnaps Maud Adams, then defaces her body as an act of demented love; "Harry Tracy" (1982) is a visually rapturous Canadian Western about a soft-hearted outlaw; "On the Edge" (1985) is an equally good-looking story about an obsessive long-distance runner, with a sexy love story involving Pam Grier that was inexplicably deleted for the film's DVD release. Dern, best known for the loonies he played in the outlandish thriller "Black Sunday" (1977) and the heartfelt Vietnam drama "Coming Home" (1978), still pops up regularly in movies big and small, though rarely in roles that fully utilize his peculiar gifts. Happily, the 2010s brought about a revivial in Dern's career, beginning with his receipt of a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 2010; just three years later, Dern earned an Oscar nomination for his leading role in Alexander Payne's plaintive dramedy "Nebraska" (2013), the favorable reception of which led to Dern joining the cast of Quentin Tarantino's ensemble Western "The Hateful Eight" (2015). A smaller role followed in Tarantino's next project, "Once Upon a Time in Hollywood" (2019).

Dern, Bruce. Actor, b. 1936. After paying his dues as a rank-and-file studio player in the early '60s, Dern ventured to weirder places in such offbeat pictures as "Psych-Out" (1968), a hippie phantasmagoria in which he plays an addled messianic type called The Seeker, and "They Shoot Horses, Don't They" (1969), in which he and the other members of an eclectic cast spin themselves to exhaustion during a dance marathon. Tall and lean, often wearing the pinched expression of a ferret, Dern became a leading man at just the right time, granting his slow-burn intensity and spaced-out line readings to several unmistakably New Hollywood productions. It says a lot that in "The King of Marvin Gardens" (1972), Jack Nicholson plays straight man to Dern's maniac; one should never underestimate a performer who could outmug Nicholson in the early '70s. The major films in which Dern is the sole lead are few, and most of them are bizarre. "Silent Running" (1972) is an elegiac drama about the last trees in space, complete with a warbly Joan Baez theme song and a tearjerker ending; "Tattoo" (1981) features Dern as a wacko who kidnaps Maud Adams, then defaces her body as an act of demented love; "Harry Tracy" (1982) is a visually rapturous Canadian Western about a soft-hearted outlaw; "On the Edge" (1985) is an equally good-looking story about an obsessive long-distance runner, with a sexy love story involving Pam Grier that was inexplicably deleted for the film's DVD release. Dern, best known for the loonies he played in the outlandish thriller "Black Sunday" (1977) and the heartfelt Vietnam drama "Coming Home" (1978), still pops up regularly in movies big and small, though rarely in roles that fully utilize his peculiar gifts. Happily, the 2010s brought about a revivial in Dern's career, beginning with his receipt of a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 2010; just three years later, Dern earned an Oscar nomination for his leading role in Alexander Payne's plaintive dramedy "Nebraska" (2013), the favorable reception of which led to Dern joining the cast of Quentin Tarantino's ensemble Western "The Hateful Eight" (2015). A smaller role followed in Tarantino's next project, "Once Upon a Time in Hollywood" (2019).

“The Descent” (2006). Writer-director Neil Marshall’s breakout movie is on par with Tobe Hooper’s "The Texas Chain Saw Massacre" (1974) for sheer, merciless terror. It also shares with that enduring shocker an artful approach to camerawork, pacing, and sound. Marshall takes his time turning a story about grief-stricken spelunkers into a frightfest about heroines besieged by underground nasties, and the movie's infinitely better for his patient style. The first forty minutes are tense and disturbing, and the last hour is breathlessly scary: Think "Deliverance" gene-spliced with "Alien." I yelped out loud several times the first time I saw “The Descent,” and creepy movies rarely affect me on that primal a level. Marshall’s jolts are expertly rendered, and there's just enough ambiguity and psychodrama to elevate the piece beyond mere pulp. FYI, the unrated edition of “The Descent” is recommended even though the gore factor is quite extreme.

"Desert Blue" (1998). Sweet and slight, this love letter to eccentricity kicks off when a professor studying roadside kitsch drags his petulant TV-star daughter to a tiny town, only to get stranded there by, of all things, a quarantine. John Heard and Kate Hudson are smartly cast as the professor and his offspring, with indie faves Casey Affleck, Christina Ricci, and Brendan Sexton III all contributing exemplary work as the resourceful townies who embrace the newcomers. Written and directed by Morgan J. Freeman, the movie is more pleasant than absorbing, but that suits the subject matter—a theme of the piece is how the easy, sometimes bizarre rhythms of small-town life intrigue the professor and charm his city-slicker daughter. Though less inspired than the movie whose narrative DNA it shares, 1981's "Local Hero," "Desert Blue" has enough charm to make the barren burg it depicts quite appealing.

"The Devil and Daniel Webster" aka "All That Money Can Buy" (1941). Walter Huston gives one of his most entertaining performances as Old Scratch in this rousing adaptation of Steven Vincent Benet's morality tale, and costar Edward Arnold matches him in sheer showboating exuberance. The story, about a farmer who sells his soul to the devil and then tries to back out of the deal, is of course great stuff, funny and absurd and thought-provoking all at once. It's the execution, however, that sparkles. William Dieterle directs with the same confidence, imagination, and grandeur he brought to 1939's "The Hunchback of Notre Dame"; Bernard Herrmann hits a magical balance of menace and delight in his irresistible score; and the look of the piece is consistently otherworldly. Ostensible lead James Craig, as the farmer, is outmatched by the two stars, which actually works for his overwhelmed character—the audience is right there with dazed Craig when Huston and Arnold, as legendary litigator Daniel Webster, set off verbal fireworks during their "trial" over the devil's legal claim to the farmer's soul. Yet the picture isn't a stuffy courtroom drama. Instead, it's a full-blooded fantasy laced with persuasive special effects like the choice bit in which Huston brands his autograph into a tree with a cigar.

"Dick" (1999). As easy a target of derision as Richard "Tricky Dick" Nixon may be, it's hard to resist the charm of this comedy about two teenybopper dogwalkers (Kirsten Dunst and Michelle Williams) who inadvertently become part of the Watergate scandal. Hanging his feather-light story on this silly premise, director-cowriter Andrew Fleming takes easygoing potshots at every infamous aspect of the "All the President's Men" era, presenting ace newshounds Woodward and Bernstein (Will Ferrell and Bruce McCullouch) like a bickering married couple; casting ace character player Dan Hedaya as a scowling Nixon; and offering up an outrageous explanation for the 18-minute gap on Nixon's secret Oval Office tapes. The piece paints itself somewhat into a corner by not being able to credibly integrate the dogwalkers into the climax of the scandal, but the movie's 94 frothy minutes are filled with winning elements, whether it's Dave Foley's anxious take on John Dean or the Day-Glo trippiness of the dogwalkers' fashions.

“Dillinger” (1973). Writer-director John Milius leavens his signature macho poeticism with a dose of unflinching docudrama realism throughout “Dillinger,” a taut story about FBI Agent Melvin Purvis’ relentless Depression-era pursuit of trigger-happy bank robber John Dillinger. Even though Milius employs grandiose dialogue and larger-than-life characterization, the incessant danger and ugliness of life in Dillinger’s gang precludes any accusations that the filmmaker is glamorizing crime. If anything, he’s communicating a favorite theme about what it means to be a primitive man in the civilized world. In that context, Warren Oates is perfect casting as Dillinger, because the actor’s unvarnished, violent style manifests in a simultaneously repulsive and seductive charm. Stoic Ben Johnson is equally appropriate as Dillinger’s opposite number, Purvis, whom Milius portrays as an elemental force of lethal justice. Supporting the stars is a terrific cast including Richard Dreyfuss, Geoffrey Lewis, Cloris Leachman, and, in her first major role, pop singer Michelle Phillips of the Mamas and the Papas. At turns exciting, funny, sad, and tragic, “Dillinger” is also consistently economical and smart, making it one of the best films that low-budget factory American International Pictures released in the ’70s.

“District 9” (2009). The unlikely story behind this Best Picture nominee is well-known: New Zealand fantasy guy Peter Jackson recruited South African filmmaker Neill Blomkamp to helm an adaptation of the megahit videogame “Halo,” and when that project fell apart, Jackson decided to keep Blomkamp and his team working by expanding the younger filmmaker’s short film “Alive in Joburg” to feature length. The ingenious story, an overtly political riff on the ’80s sci-fi franchise “Alien Nation,” depicts a near-future Johannesburg in which a derelict alien spaceship ran aground ten years before the start of the movie. The ship’s residents, reptilian aliens called “Prawns,” have been segregated into a filthy ghetto because native South Africans perceive them as drains on society. Thrown into the mix is an ineffectual government drone, Wikus (Sharlto Copely), who’s tasked with evicting the aliens to an even less desirable locale. But after a run-in with some toxic alien goo, Wikus finds his fate inextricably intertwined with that of the Prawns. The fantasy stuff is unusually smart and logical, with a slow-burn plotline borrowing from David Cronenberg’s “The Fly,” but more importantly Blomkamp’s movie matches Cronenberg’s masterpiece for emotional impact. The rare sci-fi picture that works as well on a human level as it does on the level of visual spectacle, “District 9” is a great example of what happens when filmmakers act on spontaneous inspiration instead of developing stories to death.

“Dodsworth” (1936). Walter Huston favored the rascally aspect of his uniquely American charm in many of his enduring performances, so it’s a pleasure to see him mining a different vein in this exquisitely rendered romantic drama. Huston plays a corn-fed American tycoon whose retirement in Europe is sullied by the dalliances of his superficial wife (Ruth Chatterton), a younger woman who uses her husband’s money as a means of entering the international jet set. Huston nimbly personifies a self-made man at peace with his gifts and limitations, while Chatterton sharply depicts a woman who deeply resents the inevitability of middle age. Using Sinclair Lewis’ novel as a template, director William Wyler and his team boldly chart the dissipation of a marriage, adding real emotional stakes when Huston's character finds a second chance at a fulfilling life. This might even be the ‘30s romance for people who don’t generally dig ‘30s romances (myself included), because even though it’s filled with frothy cocktail-party banter, there’s an undercurrent of tension and pain throughout the film, and the manner in which Huston’s character disdains empty socialites is a tacit commentary on the bubbliest entertainments of the era.

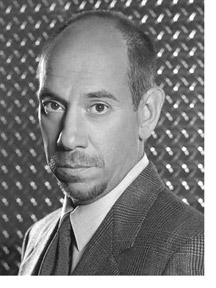

D'Onofrio, Vincent. Actor, b. 1959. I distinctly remember the experience of discovering an actor then known as Vincent Philip D'Onofrio in 1987. In June of that year, he scared the bejesus out of me as a bloated, demented cadet in Stanley Kubrick's "Full Metal Jacket." Then in July, he transformed into a blonde Adonis for a small role in the comedy "Adventures in Babysitting." And in September, he occupied a shape between those extremes as a frightened, mentally challenged crime suspect on an episode of the TV thriller "The Equalizer." By the third time I encountered D'Onofrio, I was thoroughly dazzled by his commitment and his malleability. In subsequent years, I've become more deeply impressed by his unique gifts. He's smooth and hypnotic as Orson Welles in "Ed Wood" (1994), alternately volcanic and tender as Conan creator Robert E. Howard in "The Whole Wide World" (1996), and amusingly repulsive as an outer-space monster in "Men in Black" (1997). From 2001 to 2011, of course, he enjoyed the broadest audience yet for his nimble skills by starring in "Law and Order: Criminal Intent." Even the still images during the show's opening credits, featurig D'Onofrio's Det. Goren tilting his head at peculiar angles, reflect the imagination and offbeat flavorings that he brought to "Law and Order" overlord Dick Wolf's ritualized TV universe. D'Onofrio has produced a handful of his movies, including the spirited Abbie Hoffman biopic "Steal This Movie" (2000), and he played the same character—assassination witness Bill Newman—in "JFK" (1991) and "Malcolm X" (1992). From 2015 to 2018, D'Onofrio incarnated one of his most colorful characters to date, mixing cruelty and tenderness while playing the criminal overlord Wilson Fisk in the gritty Marvel/Netflix series "Daredevil."

"The Door in the Floor" (2004). Eschewing the sentimentality that has marred some John Irving adaptations, Tod Williams' smart, funny, and frequently painful movie connects on a number of emotional and intellectual fronts, most effectively with its insight into the creative process. Jeff Bridges, in yet another performance that should have won an Oscar but instead brought him nada, nails every specific aspect of Ted Cole, a kiddie-book creator whose approach to relationships is self-serving and, we suspect, informed by profound insecurities. Over the course of a torrid summer, Ted conducts a psychologically abusive affair with a society woman, tries in vain to connect with his angelic daughter, and mentors a young writer—whom Ted is only slightly disappointed to discover is screwing Ted's heartbroken wife. And since this is an Irving piece, all of these things happen in the shadow of a tragedy. While much of what happens in the movie is melancholy, Williams infuses key scenes with broad humor; the bit wherein Ted's mistress turns the tables on her lover is particularly outrageous.

Dourif, Brad. Actor, b. 1950. From his shattering, Oscar-nominated turn as fragile mental patient Billy Bibbit in "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest" (1975) to his heartbreaking performance as a doctor vainly trying to give the sick and dying dignity in the remarkable Western series "Deadwood" (2004-2006, reunion movie 2019), Dourif has again and again proven his ability to conjure moments of incandescent emotion. Even in bizarre genre-movie roles, whether as a demonic psychopath in "The Exorcist III" (1990) or as a doomed scientist studying monsters in "Alien Resurrection" (1997), it's not unusual to find Dourif summoning such unexpected depths that a convincing tear rolls from his eye, as if the sheer intensity of his acting has overwhelmed his slight frame. Despite his great versatility and power, Dourif generally gets parts that skew toward the grotesque, and it's highly ironic that such an extraordinarily sensitive actor is the voice of a homicidal figurine in the "Child's Play" movies. There are many gems on Dourif's extensive filmography, including a handful of truly challenging movies. Of those, perhaps the most daring is John Huston's "Wise Blood" (1979), a take-no-prisoners adaptation of Flannery O'Connor's novel. As a damaged veteran who becomes a fervent preacher, Dourif commits himself to one of his few real leading roles with disquieting results.

Dourif, Brad. Actor, b. 1950. From his shattering, Oscar-nominated turn as fragile mental patient Billy Bibbit in "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest" (1975) to his heartbreaking performance as a doctor vainly trying to give the sick and dying dignity in the remarkable Western series "Deadwood" (2004-2006, reunion movie 2019), Dourif has again and again proven his ability to conjure moments of incandescent emotion. Even in bizarre genre-movie roles, whether as a demonic psychopath in "The Exorcist III" (1990) or as a doomed scientist studying monsters in "Alien Resurrection" (1997), it's not unusual to find Dourif summoning such unexpected depths that a convincing tear rolls from his eye, as if the sheer intensity of his acting has overwhelmed his slight frame. Despite his great versatility and power, Dourif generally gets parts that skew toward the grotesque, and it's highly ironic that such an extraordinarily sensitive actor is the voice of a homicidal figurine in the "Child's Play" movies. There are many gems on Dourif's extensive filmography, including a handful of truly challenging movies. Of those, perhaps the most daring is John Huston's "Wise Blood" (1979), a take-no-prisoners adaptation of Flannery O'Connor's novel. As a damaged veteran who becomes a fervent preacher, Dourif commits himself to one of his few real leading roles with disquieting results.

"Downfall" aka "Der Untergang" (2004). It's certainly not as if Hitler's final days are a subject from which storytellers have shied away, but there's nonetheless something fresh and powerful about this German take on Germany's darkest hours. Bruno Ganz, frequently cast as loveable types, is shockingly good as a palsy-ridden, paranoid, spittle-spewing Hitler, desperately setting up scapegoats, madly describing impossible dreams, and pathetically showing tenderness to the chosen few he deems loyal. The exhaustive picture, clocking in at over two and a half hours, uses Hitler as an anchor for a broader story about all the people who joined Der Fuhrer in his claustrophobic bunker, and in fact the script is based on a memoir by Hitler's last secretary. Director Oliver Hirschbiegel and his proficient collaborators create vivid reality around Ganz's towering performance, from the cracking cement walls of the bunker to the devastated nightmarescape of late-WWII Berlin.

"Dracula" [Alternate Versions] (1931). Sure, everyone's at least passingly familiar with Tod Browning's vampire story starring Bela Lugosi, which any honest horror fan will tell you is a dreadful movie that happens to contain an iconic performance. But for the adventurous viewer, there are several different means of ingesting Universal's famous take on vampirism. First off, there's the Spanish-language version of the movie, which was shot at night on the same soundstages Lugosi prowled during the day. Lusty and active where Browning's movie is chaste and dull, the Spanish-language version offers a tantalizing glimpse of what might have been—the movie clicks on every level except that of Carlos Villarias' lead performance, which, though enthusiastic, lacks the hammy elegance of Lugosi's star turn. And then there's the musically enhanced version of the Browning movie. In 1999, minimalist composer Philip Glass recorded one of his characteristically hypnotic scores for the 1931 picture, which previously had music only at the very beginning and very end. Glass' music doesn't make up for the movie's leaden pacing, but it beautifully complements the atmosphere of the film's legendary sets and photography, creating an almost entirely new movie.

"Dragonslayer" (1981). Amid other visual splendors, this grim offering (coproduced by Walt Disney Pictures!) features the most astonishing live-action dragon FX of the pre-CGI era. In a clever twist, the monster—gloriously named Vermithrax Pejorative and thankfully bereft of speech and anthropomorphization—is the last of its breed, a fading but still fearsome creature living in a lake of fire nestled inside a craggy mountain. Peter MacNichol plays a sorcerer's apprentice charged with, but woefully unprepared for, the task of dispatching Vermy. Sumptuously photographed but slow-moving and a bit too dreary for its own good, the movie features a handful of incredibly vivid sequences, notably an unfortunate virgin's close encounter with the dragon and the first full reveal of the great beast. Also of note are the picture's stunning production design and Ralph Richardson's poignant turn as the hero's mentor.

Dreyfuss, Richard. Precision instrument, b. 1947. Like a guitarist grinning during a killer solo, Dreyfuss projects unmistakable glee when he's really cooking. Maybe that's why he's been cast as so many smug characters, but from my perspective, he's more than entitled to his self-confidence—the pugnacious Brooklyn native swings through scenes like a clenched fist, maximizing every instant of screen time by stuffing performances with inventive details and that unmistakable brand of neurotic charisma. After paying the requisite dues during a decade of minor film and TV work, Dreyfuss staked his claim with a three-year hot streak. In 1973, he was psychotic gangster Baby Face Nelson in "Dillinger" and horny would-be collegiate Curt Henderson in "American Graffiti." The following year, he played a self-loathing pornographer in "Inserts" and an ambitious young Canadian in "The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz." And in 1975, he became smartass scientist Matt Hooper for "Jaws." All of the pictures displayed Dreyfuss' ability to meld comedic and dramatic elements into broadly entertaining characterizations. And while he possesses the flexibility to tamp down his extremes (as in 1977's "Close Encounters of the Third Kind") or ratchet them up (as in the same year's "The Goodbye Girl"), all of his performances are basically variations on a theme. His special gift is portraying gradations of arrogance, so in gentler roles he projects righteousness, and in brasher ones he conveys megalomania. Dreyfuss flew on autopilot for much of the '80s, a period of time marred by his affection for a certain white powder, so it was thrilling when he returned to terra firma for "Mr. Holland's Opus" in 1994. His spectacular comeback performance netted him a well-deserved Oscar nod. Much of his best work in recent years has been on television, and he's spent an awful lot of time since the mid-'90s playing unpleasant politicians. But even in inconsequential projects like the 2006 remake "Poseidon," Dreyfuss still creates incredibly vivid moments. When his tormented character sees that big wave coming, Dreyfuss' acting is so sharp that for a moment, viewers can be forgiven for hoping the picture will rise to his level.

Durning, Charles. Actor, 1923-2012. Prior to becoming an actor, the rotund but nimble Durning was a soldier, a boxer, and even a dance instructor. Appearing onscreen since the early ’60s and virtually ubiquitous during the ’70s and ’80s, he commanded an unusually flexible persona—Durning could interpret extreme villains and saintly paternal types with equal fecundity, yet he was best served by roles that included a range of shadings. In 1982’s “Tootsie,” he played a simple farmer who falls for a man masquerading as a woman, leading to a priceless line: “The only reason you’re still alive is because I didn’t kiss you.” Durning gave the quip all the malice it needed, while also revealing pride and a sort of cornpone nobility. As if further amplification of his versatility is necessary, he sang and danced the role of a corrupt politico in “The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas” the same year “Tootsie” was released. Durning’s notable performances stretched across decades, from his caustic turn as a sleazy cop in “The Sting” (1973) to his recurring role in the controversial FX series “Rescue Me” (launched in 2004). In between, he notched credits of almost every conceivable type and formed lasting professional relationships with everyone from Burt Reynolds (his employer in several movie and TV projects) and the Muppets (he’s mean ol’ Doc Hopper in the 1979 classic “The Muppet Movie”). Through it all, Durning displayed understandable confidence in his enviable strengths: smooth carriage that belied his girth, an innate relatability applicable to characters of great or minimal integrity, a supple voice that he could make silky or braying as needed.

“Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-and-Rock ’N’ Roll Generation Saved Hollywood.” To paraphrase a Kevin Smith tagline, the New Hollywood had it coming. After years in which cinephiles revered the glory days of counterculture directors, hailing their offbeat triumphs and laughing off their pharmaceutical excesses, film historian Peter Biskind put everything into a new context with his massive study of the period. Largely prioritizing bitchy anecdotes over cogent analysis—a wise strategy given how much the work of Coppola, Scorsese, and their peers has been dissected by critics—Biskind constructs an enveloping narrative in which the dissipation of the studio system and the distribution of controlled substances let wild men like Robert Evans and Dennis Hopper off their leashes. Constructed around hundreds of interviews with key players, the 1998 book builds excitement as young filmmakers of the ’60s and ’70s change their world, and then details a sobering comedown as corporate Hollywood reclaims its grip on the industry. Though his prose is often quite transporting, Biskind regularly succumbs to lesser impulses, letting interviewees air old grudges and undoubtedly inspire new ones with their backbiting and blamecasting. But since ego trips and petty parlor games were as important during the New Hollywood era as in any other chapter of Tinseltown history, the surliness is par for the course. Fast, overstuffed with incident, and touching on almost every important milestone of the period, “Easy Riders” is unlikely to be replaced by a more essential investigation of its subject. (Note: Biskind’s book was adapted into a zippy 2003 documentary by director Kenneth Boswer. Though many big names from the book did not sit for new on-camera interviews, juicy remarks by counterculture-era survivors including Peter Bogdanovich, Ellen Burstyn, Peter Fonda, Dennis Hopper, and Margot Kidder make the piece a great companion to the other 2003 documentary on the subject, the engrossing “A Decade Under the Influence.”)

“Edge of Darkness” (2010). Mel Gibson ended a long absence from the screen with this vengeance thriller that seemingly fits into his cinematic comfort zone. But upon closer inspection, the script by Andrew Bovell and Oscar winner William Monahan presents an old-school conspiracy storyline, with the vengeance angle keeping the potentially convoluted story on track. Gibson doesn’t break a sweat delivering the armed-and-dangerous goods, but the quietly impressive fireworks popping around him make this worth investigating. Danny Huston is memorably insidious as a corporate villain, and Ray Winstone contributes unexpected nuances as a covert operative with a surprising agenda that keeps the story spinning in new ways. Director Martin Campbell, the journeyman action helmer who earlier in his career shot several episodes of the 1980s British TV series on which this film is based, displays an uncharacteristically delicate touch with character scenes while still ensuring that thrills connect with maximum impact.

"Ed Wood" (1994). If you see only one movie about a talentless transvestite film director, this one's the way to go. Taking a break from his big-budget fantasies, Tim Burton found a perfect vehicle for his personal obsessions in Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski's outlandish script about Edward D. Wood Jr., the cross-dressing wannabe behind a handful of shlocktastic movies. And while Johnny Depp is sweet and fall-down funny throughout the film as Ed, whether whipping out his false teeth or rhapsodizing about his girlfriend's angora sweaters, it's the ensemble with whom the filmmakers surround Depp that elevate the movie. Martin Landau's Oscar-winning performance as Wood's doomed star player, Bela Lugosi, is a foul-mouthed pleasure; Jeffrey Jones achieves a perfect balance of pomposity and self-awareness as prognosticator Criswell; and Bill Murray gives one of his wickedest turns playing a pre-op transsexual named Bunny. The look and sound of the movie are so endearingly kitschy that you can almost hear Burton giggling as he puts the thing together, but unlike other directorial larks, the story never gets lost in the stylistic indulgences—the Lugosi subplot is as heartbreaking as the main story about Wood's adventures is heartwarming.

"Ed Wood" (1994). If you see only one movie about a talentless transvestite film director, this one's the way to go. Taking a break from his big-budget fantasies, Tim Burton found a perfect vehicle for his personal obsessions in Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski's outlandish script about Edward D. Wood Jr., the cross-dressing wannabe behind a handful of shlocktastic movies. And while Johnny Depp is sweet and fall-down funny throughout the film as Ed, whether whipping out his false teeth or rhapsodizing about his girlfriend's angora sweaters, it's the ensemble with whom the filmmakers surround Depp that elevate the movie. Martin Landau's Oscar-winning performance as Wood's doomed star player, Bela Lugosi, is a foul-mouthed pleasure; Jeffrey Jones achieves a perfect balance of pomposity and self-awareness as prognosticator Criswell; and Bill Murray gives one of his wickedest turns playing a pre-op transsexual named Bunny. The look and sound of the movie are so endearingly kitschy that you can almost hear Burton giggling as he puts the thing together, but unlike other directorial larks, the story never gets lost in the stylistic indulgences—the Lugosi subplot is as heartbreaking as the main story about Wood's adventures is heartwarming.

"Eight Men Out" (1988). Arguably the most entertaining of John Sayles' stories about the plight of the working man, this masterful ensemble piece investigates the notorious Chicago White Sox of 1919, who threw the World Series and blackened the team's name for decades. With the brisk pacing and complex plotting of a great novel, Sayles lays out how the team's owner exploited his players like they were interchangeable assembly-line workers, and delineates how opportunism, jealousy, bitterness, and desperation contributed to the players' decision to cast off sportsmanship. The baseball scenes are exuberantly filmed, adding the visual excitement sometimes missing from Sayles' earnest movies, and the acting is spectacular across the board. Sayles regular David Strathairn is the heart of the piece as the team's conflicted key man, and he's abetted by an eclectic cast featuring name players (John Cusack, Charlie Sheen) and more unexpected casting (Sayles and literary giant Studs Terkel as color commentators).

Ejiofor, Chiwetel. Actor, b. 1974. An Englishman of Nigerian descent, Ejiofor has a deceptively quiet screen presence. Whether playing heroes, villains, or everymen, Ejiofor consistently brings potent humanity to his parts, opting for emotional credibility over dramatic fireworks. He made his first big international splash in Stephen Frears' "Dirty Pretty Things" (2002), playing an African immigrant caught up in a bizarre conspiracy involving black-market body parts. Warm and vulnerable even during tense scenes, he was an unusual but effective leading-man choice for the Hitchockian thriller. A peculiar assortment of roles followed, from the lovesick Brit he played in "Love Actually" (2003) to the New York cop he portrayed in "Inside Man" (2006). In between those roles, he brought unexpected depth to the part of a futuristic assassin in the sci-fi actioner "Serenity" (2005). Ejiofor's showiest role to date is in the English comedy "Kinky Boots" (released in the U.S. in 2006), featuring the actor in gaudy wigs and gaudier footwear as a flamboyant drag queen. He also memorably teamed with Denzel Washington in a pair of ambitious thrillers, the aforementioned “Inside Man” as well as “American Gangster” (2007). In 2013, Ejiofor finally won widespread mainstream attention for this incendiary performance in “12 Years a Slave,” which earned him an Oscar nomination; playing citizen-turned-slave Solomon Northrup, Ejiofor sang a heartbreaking ballad of suffering infused with the theme of personal growth. Since then, he's balanced supporting roles in blockbusters with more challenging work in smaller projects, even pulling double-duty as the writer of “The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind” (2019).

"Electra Glide in Blue" (1973). For a vivid snapshot of how wild American movies got in the Me Decade, look no further than this oddity starring diminutive tough guy Robert Blake. James William Guercio—a music producer who helped launch the bands Chicago and Blood, Sweat & Tears—indulged his cinema jones by directing a downbeat parable about a motorcycle cop whose black-and-white ideas of justice are challenged when he enters the murky milieu of homicide investigation. On a narrative level, the film is all over the place, realistic at one moment and pretentiously metaphorical the next, but the story is weirdly gripping, and several people make unique contributions. Blake's combative nature bounces against the confines of his naïve character to poignant effect, Mitchell Ryan adds unexpected colors to his portrayal of a tough-talking veteran cop, and cinematographer Conrad L. Hall provides striking contrasts—the indoor scenes are cramped and moody, the outdoor passages expansive and beautiful. In addition to directing, Guercio composed the movie's ballsy, imaginative score, which plays a key role in the memorably overwrought finale.

"The Emerald Forest" (1985). An ingenious adventure that occasionally goes off the rails, John Boorman's lush jungle story depicts a white man's search for the young son who disappeared into the wilds of the Amazon rainforest. Powers Boothe gives one of his most invested performances as the driven father, and the director's son, Charley, appears as the adolescent version of the lost boy. The movie gets away from Boorman during bits involving hallucinogens and people identifying with animals, but there's a powerful stretch depicting the fate of native women abducted from their remote village. Perhaps a little on-the-nose in its commentary about civilized man being the real savage, the picture nonetheless reiterates the gift for photographing the natural world that Boorman displayed in "Deliverance," and the ending is just about perfect.

“The Entity” (1981). A product of the early-’80s horror boom that peaked with hits like “Poltergeist,” this lurid enterprise concerns a Southern Californian housewife suffering sexual assaults by an otherworldly assailant. I was hesitant to spotlight this movie because I loathe most films predicated on violence against women, but there’s something memorable about this intense thriller, directed by journeyman Sidney J. Furie from a novel and script by Frank De Felitta. Three reasons why: moody nighttime photography by Stephen H. Burum, a throbbing score by Charles Bernstein (with more than a nod to “Tubular Bells”), and a committed lead performance by Barbara Hershey. Even in the sleaziest scenes (and there are plenty), Hershey plays every moment with complete sincerity, effectively sketching her character’s descent not into madness but into pained acceptance of a changed reality. Unusually long dialogue scenes give Hershey and co-star Ron Silver, as her well-intentioned shrink, lots of room to illuminate dark emotional territory; these simplistic but robust pop-psychology scenes nearly justify the film’s extremes. “The Entity” is unquestionably “Exorcist Lite” in execution and intent, but it’s still disturbing and vivid.

“Escape from Fort Bravo” (1953). On first glance, this John Sturges-directed actioner might seem to be a standard-issue Western, but upon closer inspection some unique qualities become visible. William Holden, at his caustic best, plays a brutal Union officer in charge of Confederate prisoners in an Arizona fort surrounded by hellish desert and hostile Apaches. The film’s quasi-successful attempt to paint Holden’s character as a poetic warrior, in tandem with Holden’s inherent charisma, fills the talky bits of the film with surprising flashes of humanity. Where the movie achieves unqualified impact is during Sturges’ extraordinarily staged battle scenes, particularly the climax. It’s hard to recall another movie from the same era that features a showdown as genuinely frightening as the long climax during which the principal characters get caught in open country with bloodthirsty braves closing in from every direction.

"Escape From New York" (1981). I groove on the style of this movie more than that of any other, which explains why I couldn't care less about the glaring script problems. From Dean Cudney's shadowy photography to the vibrant John Carpenter/Alan Howarth score to Kurt Russell's commanding turn in the preposterous role of hero-turned-thug-turned-hero-turned-nihilist Snake Plissken, I love just about everything that happens during this movie's 99 popcorn-worthy minutes. The premise is ingenious (Manhattan becomes a dumping ground for America's worst criminals), the cast of B-movie icons guarantees scenery-chewing of the first order, and the action is solid stuff sparked by a few real jolts. Yet it's the momentum of the thing that wins me over. As that first ominous synth note brings the opening theme up to accompany stark white-on-black title cards, cowriter-director Carpenter establishes a mood that never relents until the last closing title scrolls. I could watch the sleek sequence of Plissken flying his hang glider from Liberty Island to the World Trade Center, accompanied by Debussy music played on Carpenter/Howarth keyboards, all day long.

"Escape From New York" (1981). I groove on the style of this movie more than that of any other, which explains why I couldn't care less about the glaring script problems. From Dean Cudney's shadowy photography to the vibrant John Carpenter/Alan Howarth score to Kurt Russell's commanding turn in the preposterous role of hero-turned-thug-turned-hero-turned-nihilist Snake Plissken, I love just about everything that happens during this movie's 99 popcorn-worthy minutes. The premise is ingenious (Manhattan becomes a dumping ground for America's worst criminals), the cast of B-movie icons guarantees scenery-chewing of the first order, and the action is solid stuff sparked by a few real jolts. Yet it's the momentum of the thing that wins me over. As that first ominous synth note brings the opening theme up to accompany stark white-on-black title cards, cowriter-director Carpenter establishes a mood that never relents until the last closing title scrolls. I could watch the sleek sequence of Plissken flying his hang glider from Liberty Island to the World Trade Center, accompanied by Debussy music played on Carpenter/Howarth keyboards, all day long.

"Excalibur" (1981). As if the Wagner music underlying climactic scenes wasn't a hint, the genius of John Boorman's King Arthur movie is that it's presented as an opera—not in the musical sense, but in the sense that every emotion displayed on screen is pitched to earth-shaking intensity. By casting then-unknowns (watch for Gabriel Byrne, Liam Neeson, and Patrick Stewart), and, in the key role of Merlin the Magician, ringer Nicol Williamson, Boorman crafts such an engrossing illusion that for two hours and twenty minutes, it's easy to believe that Nigel Terry is the Arthur of myth, Nicholas Clay is Lancelot, and so on. Boorman puts his stamp on every aspect of the legend, determining that armor should glisten like polished silver, that English forests are as vibrant and mysterious as jungles, and that magic and sex can rattle the universe. The raunch and gore are severe, the dialogue can sound pretty campy, and Boorman's obsessive desire to squeeze in every favorite bit of Arthurian lore makes the movie a long haul. But the best parts of this movie are unforgettable. If nothing else, Boorman's success at making people take King Arthur seriously just six years after "Monty Python and the Holy Grail" was a magic act in and of itself.

"The Exorcist III" (1990). Novelist-screenwriter William Peter Blatty walked away from the success of "The Exorcist" (1973) with lots of unfinished business, but it seemed that after Hollywood derailed the potential franchise with the unwatchable "Exorcist II: The Heretic" (1977), Blatty would have to content himself with revisiting the subject matter in books. So it was a surprise when "The Exorcist III" appeared in 1990, with Blatty writing and directing the adaptation of his novel "Legion." Dumping both the Regan MacNeil character and all her pea-soup trappings, the picture is a supernatural mystery centered around world-weary Det. Kinderman (George C. Scott, standing in for the late Lee J. Cobb). The story is convoluted and strange, tricky business about a killer with seemingly impossible connections to the events of the first movie, but what's most compelling about Blatty's picture are the offbeat jolts and even more offbeat character bits. Fully utilizing the skills of a tremendous cast—Brad Dourif, Ed Flanders, Jason Miller, Lee Richardson, Nicol Williamson, Scott Wilson, and of course leading man Scott—Blatty fills the movie with peculiar activity and dialogue, creating a far richer tapestry than anyone might expect from the third iteration of a horror series. (Adventurous viewers are encouraged to seek out the alternate cut featured on the movie's Scream Factory Blu-Ray—by inserting grainy dubs of deleted scenes, the alternate version approximates what Blatty originally set out to make, thus forefronting grim intimacy as opposed to the theatrical version's FX-driven grandiosity.)

"A Face in the Crowd" (1957). Media satire at its most merciless, Elia Kazan's energetic drama follows the ascension of Larry "Lonesome" Rhodes, a charismatic Southerner whose straight talk turns him into America's favorite pundit. Andy Griffith, a million miles from Mayberry, plays Rhodes as an embittered drunk who evolves into a lascivious megalomaniac. It's an astounding performance made all the more remarkable by how it clashes with the star's nice-guy image; the sight of Griffith manipulating pretty young things into bed is quite shocking. Budd Schulberg, the literate social commentator who wrote Kazan's "On the Waterfront" (1954), methodically tracks how Rhodes gets discovered by unsuspecting broadcaster Marcia Jeffries (Patricia Neal), then illustrates with great precision how Rhodes takes the reins of his career to the detriment of everyone around him. Like the same year's "Sweet Smell of Success," the movie shows a popular figure choosing power over love, and developing contempt for the audience that gave him that power. In some ways Kazan's most exciting picture, with its sharp-tongued musical passages and frenetic montage sequences, "A Face in the Crowd" has lost none of its relevance or magnetism.

“Fair Game” (2010). Of the myriad crimes committed by the administration of George W. Bush, one of the most brazen was outing CIA agent Valerie Plame in order to distract the public from inflammatory comments made by her husband, diplomat Joe Wilson, who revealed that the “research” behind claims of Iraqi WMDs was bogus. Doug Liman’s taut dramatization of this story illuminates just how insidious the Bushies were, while also acknowledging the devious skill of their political gamesmanship. Better still, “Fair Game” mostly resists the temptation to overdramatize, focusing on the human impact of the situation. Naomi Watts plays Plame as a spy so experienced at suppressing her emotions that it takes time for her to realize how deeply she was violated, and Sean Penn plays Wilson as a hot-headed idealist whose people skills get steamrolled by his over-caffeinated self-righteousness. The actors form a potent combination, illustrating the fraught dynamics between an emotionally distant woman and a hypersensitive man. Liman surrounds his stars with uniformly great actors, including Sam Shepard (in a sharp cameo as Valerie’s dad) and David Andrews (in a chilling supporting role as White House insider “Scooter” Libby). Bush apologists may complain that the heroes’ characterizations are treated with kid gloves while the Bushies are portrayed as bullies, but since W.’s people thought Plame was “fair game,” they’re in no position to complain.

“Far From Heaven” (2002). The last thing one might have expected from arthouse fave Todd Haynes was a tribute to the decidedly studio-bound movies of director Douglas Sirk, yet Haynes crafted something truly moving when he reconfigured the narrative DNA of Sirk’s vintage weepies. Meshing retro style and modern sensibilities, Haynes found a clever way to examine the themes of suburban hypocrisy, miscegenation, and repressed homosexuality. In a starry-eyed performance full of choked emotion, Julianne Moore plays Cathy, a ’50s housewife whose husband (Dennis Quaid) is reexamining his sexual identity, and whose black gardener (Dennis Haysbert) seems like a possible soul mate. It’s a foregone conclusion that Cathy’s situation will end in tears, so watching her make the heroic effort to first hold her life together, and then reach for something society says she can’t have, is excruciating. Moore is so perfectly simpatico with the parameters of Haynes’ experiment that it’s as if she was made to play Cathy. Haysbert and Quaid are equally wonderful, subtly revealing the agony of soulful people who wear false fronts. In keeping with Sirk’s approach, Haynes drapes the wrenching drama in beautiful clothes, lush photography, and an elegantly melodramatic score (by veteran composer Elmer Bernstein).

Farina, Dennis. Actor, 1944-2013. Throughout his acting career, the endlessly watchable Farina gave the air of a man who couldn't believe his luck. A former Chicago detective discovered by Windy City auteur Michael Mann, Farina made his discreet movie debut with a small part in Mann's "Thief" (1981), then plugged away at perfunctory roles until his cinematic patron gave him opportunities to demonstrate how quickly he'd developed a distinctive screen presence. First as a charismatic crook in occasional episodes of the Mann-produced series "Miami Vice" (appearing from 1984 to 1989), then as a steely FBI boss in Mann's feature "Manhunter" (1986), and finally in the leading role of a Chicago cop (such a stretch!) on Mann's cult-fave series "Crime Story" (1986-1988), Farina consistently displayed intensity, depth, and roguish charm. Parallel with his early dramatic work, Farina revealed impressive comic skills during a riotous performance as an anxious mobster in "Midnight Run" (1988), wherein he memorably berates underlings with imaginative threats. Farina finally cemented his stature with another comic part, in "Get Shorty" (1995), which led to a brief flirtation with leading roles. At his most appealing when smiling like a man who won the lottery and purring lines in his unmistakable Chi-caw-go accent, Farina slipped comfortably into the late Jerry Orbach's shoes by starring in "Law and Order" from 2004 to 2006, then plied the character actor's trade until his death at the age of 69 in 2013.

Farnsworth, Richard. Actor, 1920-2000. After notching scores of credits as a stuntman beginning in the late 1930s, Farnsworth sought a new niche in movies once age made the rough stuff a challenge. The switch paid off when director Alan J. Pakula cast the grizzled industry vet in “Comes a Horseman” (1978), a ponderous Western that nabbed Farnsworth an Oscar nomination for his turn as a folksy type named Dodger. As unlikely a rising star as has ever graced the screen, the native Californian lucked out again when a casting call went out for “The Grey Fox” (1982), a soft-spoken Canadian romp about an aged outlaw who returns to crime. With his gentlemanly comportment and rootsy twang, Farnsworth infused the elegiac movie with grace and likeability. An erratic run of movies followed, mostly routine oaters and family pictures in which the actor imparted frontier wisdom, but his career closed with a grace note when he scored a second Oscar nomination for the quirky road movie “The Straight Story” (1999). Farnsworth died, by his own hand, a year after the picture’s release.

Feore, Colm. Actor, b. 1958. With a demeanor as cool as the icy winds that blow through his adopted country of Canada, Feore grants crisp elegance to roles as authority figures and unsettling ruthlessness to turns as villains. Tall and regal, Feore notched years of stage and screen work before becoming familiar to international audiences in the ’90s. He played the title character in Francois Girard’s experimental biopic “32 Short Films About Glenn Gould” (1994), then reteamed with Girard to portray an auctioneer in “The Red Violin” (1998). A slew of high-profile roles followed, with Feore striking sparks as a Southern litigator in “The Insider” (1999) and raising hackles as a demonic manipulator in the Stephen King miniseries “Storm of the Century” (also 1999). He further demonstrated his versatility by appearing in a 2000 Public Theater production of “Hamlet” and incarnating another lawyer in the 2002 feature version of “Chicago.” Now comfortably nestled in the ranks of well-regarded character actors, Feore consistently distinguishes himself with his signature style of commanding diction and poise.

Ferrer, Miguel. Actor, 1955-2017. Born to showbiz royals Jose Ferrer and Rosemary Clooney, Ferrer cut his teeth with smallish TV and movie parts for several years before devouring the role of ambitious corporate prick Bob Morton in "RoboCop" (1987). Among his many shining moments in the picture, Ferrer empties a men's room with his arrogant talk about his boss, and then sniffs blow off a hooker while celebrating his ill-gotten gains. Ferrer turns Morton into slime of the first order, exactly the sort of character for whom the cliché "a bad guy you love to hate" was coined. Equally adept at playing intense and laconic characters, and possessed of an arresting voice that rode low and smooth, Ferrer aggregated a freewheeling filmography containing everything from the socially conscious artistry of Steven Soderbergh's "Traffic" (2000), in which he plays a pragmatic drug dealer, to the lowbrow absurdity of "Fish Heads" (1978), a music video for the cult-fave novelty song. From 2001 to 2007, Ferrer essayed the frequently surprising role of medical examiner Dr. Garret Macy on the forensic drama "Crossing Jordan." At the time of his death, he was in the midst of another long run on a popular procedural, "NCIS: Los Angeles," which featured Ferrer from 2012 to 2017.

Ferrer, Miguel. Actor, 1955-2017. Born to showbiz royals Jose Ferrer and Rosemary Clooney, Ferrer cut his teeth with smallish TV and movie parts for several years before devouring the role of ambitious corporate prick Bob Morton in "RoboCop" (1987). Among his many shining moments in the picture, Ferrer empties a men's room with his arrogant talk about his boss, and then sniffs blow off a hooker while celebrating his ill-gotten gains. Ferrer turns Morton into slime of the first order, exactly the sort of character for whom the cliché "a bad guy you love to hate" was coined. Equally adept at playing intense and laconic characters, and possessed of an arresting voice that rode low and smooth, Ferrer aggregated a freewheeling filmography containing everything from the socially conscious artistry of Steven Soderbergh's "Traffic" (2000), in which he plays a pragmatic drug dealer, to the lowbrow absurdity of "Fish Heads" (1978), a music video for the cult-fave novelty song. From 2001 to 2007, Ferrer essayed the frequently surprising role of medical examiner Dr. Garret Macy on the forensic drama "Crossing Jordan." At the time of his death, he was in the midst of another long run on a popular procedural, "NCIS: Los Angeles," which featured Ferrer from 2012 to 2017.

"fflokes" aka "North Sea Hijack" (1980). A pleasant complement to Roger Moore's Bond outings, this competently mounted thriller casts Moore against type as a reclusive, woman-hating, cat-loving eccentric who happens to be a master at planning and executing high-seas commando missions. These skills prove useful once the rudimentary plot, about the hijacking of oil rigs off the coast of England, kicks into gear. Featuring a colorful cast (James Mason, Michael Parks, Anthony Perkins), the Andrew V. McLachlan-helmed picture is routine excepting the characterization of Rufus Excalibur ffolkes (Moore), a unique protagonist who deserved another screen outing, or at least a more energetic debut. Worth a casual Saturday afternoon viewing for fans of the high-adventure genre and especially for those eager to see Moore somewhat out of his element, the movie also benefits from Perkins' droll villainy.

Fichtner, William. Actor, b. 1956. Given his sleek, vaguely otherworldly looks, it probably was only a matter of time before someone cast Fichtner as an alien, hence his role on the weekly TV creepfest "Invasion" (2005-2006). Right from his first major movie role, as a manipulative baddie in Steven Soderbergh's noirish thriller "The Underneath" (1995), Fichtner has projected a leonine, predatory grace, with intense blue eyes peering out from beneath his imposing brow. Usually conveying the sense that he knows a great deal more than other characters, and for that matter probably more than the audience, Fichtner adds elegance to villainous roles, and sensitivity to gentler parts. He's able play a corporate carnivore (in 1995's "Heat") and a warm, sightless astronomer (in 1997's "Contact") with equal aplomb, just as he can play a lustful cop (in 1999's "Go") and a square-jawed astronaut (in 1998's "Armageddon"). Fichtner has evolved into such a compelling presence that he need not even be seen to make an impact: In the 2005 hit "Mr. & Mrs. Smith," he's the offscreen counselor who leads assassins Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt through a rap session about their unusual marriage. Steady work on TV has further raised Fichtner's profile, thanks to long runs on the gritty drama "Prison Break" (appearing as an FBI agent from 2006 to 2009) and the acclaimed sitcom "Mom" (appearing as a disabled former stuntman from 2016).

"52 Pick-Up" (1986). One of the first Elmore Leonard adaptations to really grasp the wry poetry of his dialogue, this sleazy John Frankenheimer thriller careens recklessly from supple character scenes to exploitive nudity to gruesome violence. Yet somewhere amid the lurid sensations is a taut cat-and-mouse game that pits two extraordinary actors against each other with highly entertaining results. Roy Scheider stars as a successful businessman whose life is upended when a smooth-talking crook (John Glover) produces evidence of Scheider's infidelities. Scheider, the fuse for his trademark slow burn lit, engages in a steadily escalating duel with Glover, who's funny as hell as a would-be mastermind saddled with idiot cohorts. Watching these two actors go at each other is a nasty treat, with Leonard's resourceful plot pushing their characters deeper into each other's worlds. Clarence Williams III is a standout as Glover's druggy accomplice, and Frankenheimer is generous with ogling views of starlets Kelly Preston and Vanity.

"The Film Encyclopedia." Despite many previous and subsequent contenders to the top spot, Ephraim Katz's masterwork remains the sole indispensable reference volume for movie buffs. First published in 1979 with the proportions and density of a phone book, Israeli scholar Katz's monumental text features bios and filmographies for thousands of movie people, from actors to producers to technicians, as well as definitions of key terms, overviews of genres, and other useful information. Boldly excluding write-ups of individual movies, Katz catered to scholars and fans who enjoy exploring pockets of cinema by tracking the output of particular directors or digging into, say, the history of Japanese film. For the better part of two decades, prior to the mainstream adoption of such online directories as the Internet Movie Database, Katz's book was the first stop for anyone seeking thorough information about the liveliest art. The author died before completing the second edition, which appeared in 1994 with new authors updating and adding to Katz's original text, and the franchise endures with the seventh edition, published in 2012. Offering an intelligent, cool-headed alternative to more opinionated guides (notably Leslie Halliwell's and David Thomson's), "The Film Encyclopedia" retains its relevance in the digital age by preserving the spirit of Katz's original book—academic but not dry, affectionate but not starry-eyed.

"First Blood" (1982). It kills me that this terrific action picture is now best known as the beginning of a jingoistic franchise, because the first screen appearance of tormented ex-Green Beret John Rambo is tough and provocative. When shaggy-haired Rambo (Sylvester Stallone) ambles into a small town, he immediately provokes the ire of a prejudiced sheriff (Brian Dennehy). The two men push each other's buttons, their brawl growing more intense until it explodes with Rambo's violent escape from a police station. All-out war ensues, with Rambo picking off the cops, National Guardsmen, and civilians who hunt him in the woods surrounding the town. The great thing about the picture is that neither character is fully heroic or villainous. Rambo responds to abuse with outsized ferocity, and the sheriff's heavy-handedness stems from a sincere desire to protect his town. The movie also touches on the interesting issue of what a country does with its killing machines when the time for killing is past. Though mostly an exciting adventure picture with lots of gunplay, chases, and explosions, the movie features Stallone's second-most iconic performance; he's quite affecting in the most important scenes. Watch for a young David Caruso in a small part, and beware the closing-credits tune sung by Sly's brother Frank.

"First Blood" (1982). It kills me that this terrific action picture is now best known as the beginning of a jingoistic franchise, because the first screen appearance of tormented ex-Green Beret John Rambo is tough and provocative. When shaggy-haired Rambo (Sylvester Stallone) ambles into a small town, he immediately provokes the ire of a prejudiced sheriff (Brian Dennehy). The two men push each other's buttons, their brawl growing more intense until it explodes with Rambo's violent escape from a police station. All-out war ensues, with Rambo picking off the cops, National Guardsmen, and civilians who hunt him in the woods surrounding the town. The great thing about the picture is that neither character is fully heroic or villainous. Rambo responds to abuse with outsized ferocity, and the sheriff's heavy-handedness stems from a sincere desire to protect his town. The movie also touches on the interesting issue of what a country does with its killing machines when the time for killing is past. Though mostly an exciting adventure picture with lots of gunplay, chases, and explosions, the movie features Stallone's second-most iconic performance; he's quite affecting in the most important scenes. Watch for a young David Caruso in a small part, and beware the closing-credits tune sung by Sly's brother Frank.

"The Fisher King" (1991). Terry Gilliam's warmest movie is an engaging flight of fancy overflowing with wiseass New York attitude and intoxicating romantic bliss. Mostly eschewing the overwhelming visual style of his more personal movies, Gilliam nonetheless puts his unmistakable stamp onto Richard LaGravenese's bonbon of a screenplay, often letting his ace players have the run of the movie. Jeff Bridges, brilliantly nasty, plays an asshole DJ whose loose lips spark an urban tragedy. Years later, he's a washed-up drunk who stumbles onto an overbearing loon (Robin Williams) with an unexpected connection to the DJ's past. An outrageous quest ensues, and the journey is spiced by the presence of a brassy video-store owner (Mercedes Ruehl) and a misfit office drone (Amanda Plummer). Flying high on heartfelt whimsy, the story ventures deep into the incredible while still retaining its strange brand of narrative authenticity.

“Five Came Back” (1939). A progenitor of the modern disaster movie, this taut little number about a plane crash in cannibal territory crystallizes the beloved genre trope of fate choosing who survives trying circumstances. Directed by studio-era journeyman John Farrow and benefiting greatly from the moody cinematography of RKO ace Nick Musuraca, the picture boasts among its credited writers industry titan Dalton Trumbo and cult-fave novelist Nathanael West. The result of all this talent converging on a pulpy narrative is that every scene pulses with intensity and, to a surprising degree, sociopolitical commentary—check out how the seemingly crazy-eyed crook turns out to have the most pristine morality of any of the stranded passengers. Adding to the movie’s curiosity factor is the presence of young Lucille Ball in an uncharacteristically salty role. Creepy and provocative, this is a “B” with brains.

“The Fixer” (1968). Yakov Bok (Alan Bates) is a Jewish handyman who passes for Gentile in order to get work outside of his ethnic ghetto in 1911 Russia. When he’s framed for murder in an act of cold-blooded political opportunism, Yakov abandons his previous political apathy and evolves into an activist of ferocious intensity. This transformation puts him at odds with Count Odoevsky (David Warner), the official with the most to gain from a demonstration of contrition on Yakov’s part. As scripted by Dalton Trumbo from Bernard Malamud’s novel, the story is a strident revolt against dictatorial government practices, a theme with which Trumbo became intimately familiar during his years on Hollywood’s anticommunist blacklist. And if some of Trumbo’s scenes veer toward speechifying, director John Frankehenheimer keeps everything loose and active with his typically restless camera and propulsive pacing. Some of the Christ allegories go over the top, but the film never wavers in its disturbing depiction of oppression and suffering.

Flanders, Ed. Actor, 1934-1995. Midwesterner Flanders, with his soulful eyes and warm demeanor, won Emmys for all three of his signature roles—as the 33rd president in "Harry S. Truman: Plain Speaking" (1976), as Phil Hogan in Eugene O'Neill's "A Moon for the Misbegotten" (1975), and as Dr. Donald Westphall in the series "St. Elsewhere," on which he starred from 1982 to 1987. And though he worked primarily in television, he brought his memorable blend of brusqueness and compassion to the big screen on several notable occasions. He reprised his Truman characterization in "MacArthur" (1977), effectively illustrating the president's bewilderment at the behavior of the titular general, and he fit smoothly into the humanistic ensembles of writer-director William Peter Blatty's spiritual thrillers "The Ninth Configuration" (1980) and "The Exorcist III" (1990). In Blatty's movies in particular, Flanders conveys such aching depth that it's as if his characters' souls are crying.

“Fleetwood Mac: Destiny Rules" (2004). The long soap opera that is the life of the rock band Fleetwood Mac is familiar stuff for even casual fans, dating back to the stew of romance and break-ups that produced the outfit’s seminal “Rumours” album in the ’70s. But as this surprisingly penetrating behind-the-scenes doc reveals, the tensions that made the band so fascinating during its commercial heyday remain just as evident, if perhaps more cleverly repressed, in the nostalgia-tour years. Following a hugely successful reunion tour in the late ’90s, the band (minus ’70s member Christine McVie) reconvened for a full album of new material, using singer-songwriter Lindsey Buckingham’s stockpile of unrecorded solo tunes as a starting point. Buckingham, grandiose drummer Mick Fleetwood, and recovering-alcoholic bassist John McVie assembled basic tracks to Buckingham’s exacting specifications before Stevie Nicks joined the fray to sprinkle her peculiar fairy dust onto the project. Watching Buckingham kowtow to Nicks’ idiosyncratic ideas is painfully compelling not only because they used to be lovers, but because he so clearly understands the business dynamics at work: A Lindsey Buckingham record sells thousands, but a Lindsey Buckingham record disguised as a Fleetwood Mac album featuring Stevie Nicks sells millions. The resulting music, released as the album “Say You Will,” may not be the most memorable in the band’s discography, but the human drama captured in this unflinching doc by director/producer Kyle Einhorn is quietly unforgettable, at least for fans who have watched the Buckingham-Nicks epic unfold over the course of three decades.